12 Questions for a Writer: Rachel Lance

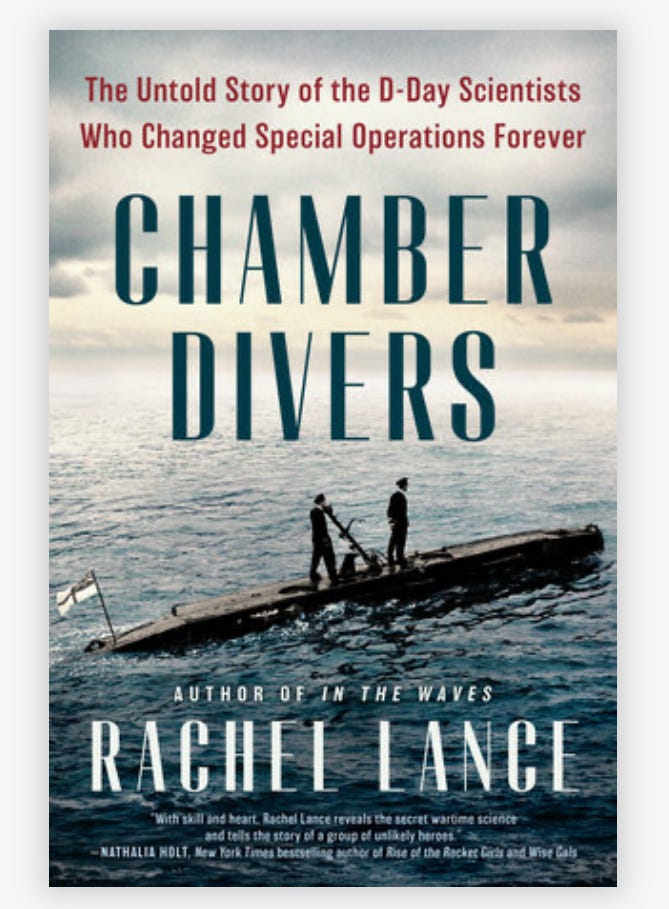

Rachel Lance is an author, expert SCUBA diver, and PhD biomechanical engineer. Her new book, Chamber Divers, tells the story of the D-Day scientists who changed special operations.

1. Rachel, tell us about yourself, what have you written, and why?

I'm a PhD biomedical engineer specializing in injury biomechanics, but don't worry, nobody knows what that means, not even my own parents. The summarized explanation is that I use the principles of engineering to assess the human body and determine when *WE* will break, as opposed to predicting when a bridge will collapse or a car will crumble. I specialize in extreme environments because I love the idea of helping people survive places and events we can't survive on our own, and that means I do a lot of work with explosives and undersea medicine.

I work as an experimental scientist at Duke University with half of my time, and with the other half of my time I write books. Chamber Divers is my second book, coming out April 16, 2024, and it's a non-fiction story about a group of scientists ("nerd folk") who conducted a series of wild and extremely dangerous experiments on themselves during the Blitz of London and the following bombings during WWII. What they did would never be allowed today and they almost all got seriously injured in the process - think broken spines, dislocated jaws, blowing themselves up, inducing multiple seizures - but they enabled the scouting of the beaches of Normandy prior to D-Day and the clearance of the underwater ordnance using the first rebreathers in the days after.

I decided to write this book after I stumbled on a scientific paper that the group published about carbon dioxide. They published it in 1941, which means the science was done the year before in 1940, and they were working out of a lab in London. That was the Blitz! I couldn't figure out why the hell anyone would care about carbon dioxide tolerance while they were being bombed in their homes, so I kept running down the rabbit hole until I figured out the true, classified purpose of what they were doing: planning for a beach landing in France. At that point, because they all died before the details were declassified and they could speak for themselves, I knew I wanted to tell their story so the world could know what they had achieved.

2. What is it that draws you to writing?

At first, writing sucked me in because it's an excuse to sit at your laptop and gush about your favorite topic all day, but after my first book came out, my reasons changed. For that first book, In the Waves, I got to talk about explosives, explosions, and blast trauma for multiple entire chapters, and given how much I love blast science that was basically a dream job. However, when an excerpt from that book got published in Smithsonian Magazine, including an explanation of blast trauma to the lungs, suddenly my inbox was filled by veterans who said they'd never before found a readable explanation of how blast traumas occur. That experience upended my motivations because, while I do love writing these stories, those emails made me realize that books are also an opportunity to communicate in an understandable way the nitty-gritty, obsessively detailed, intensely jargon-riddled knowledge of the nerd scientists out to the people who actually use it in real life. I also get to trumpet the achievements of people who deserve a little praise, and that's a great combination.

3. Tell us about the process you undertook to write this book?

The process for this book was intense quantities of archival research. This scientific group left behind records, and thankfully those records were preserved in archives, but since they were operating from the inside of hyperbaric chambers they were mostly writing on tiny scraps of paper in sloppy script. I had to piece together the stories of the experiments from a few thousand of those along with reports spread across the UK, and most importantly, keep each detail connected to its source so that I could cite it properly. Also, it was during the pandemic. My master timeline document for the story is over 80 pages long, single-spaced, and I've got a spreadsheet listing their almost 700 experiments. It wasn't like putting together puzzle pieces, it was more like reassembling a shattered glass window. Once I did that, though, the stories were so rich with detail that I felt like they wrote themselves.

4. What did you learn in the process and what surprised you?

This might not be the answer you're expecting, but in the process of putting together the stories, I also assembled that spreadsheet of 700 experiments. That means I now have a total of 1,200 data points with human beings in experiments that would be considered too dangerous to allow today. It was a treasure trove of data! These scientists were meticulous and their records were extraordinary in their detail and consistency, which means I can actually use these experiments to put together better, more informative risk guidance for modern-day warriors who use oxygen or mixed-gas rebreathers underwater. Know any??

5. As a matter of fact, I do. Would you do it again?

Absolutely, I don't even have to think about that. I am more proud of the chapter describing the D-Day landings than anything else I have ever written. It took me months to tell the story of those landings from the perspective of the people who were actually there, and I'm incredibly proud to have been able to include their voices.

6. What do you want people to take away from this book?

I want people to leave this book with two points. First, that real science takes literal blood, sweat, and tears, and it's nothing like in the movies. These people put their own bodies and lives on the line several days a week for literal years, often spacing out the experiments based on when they were physically able to stand again. In real science there's never a montage of a guy examining green liquid in beakers then *poof* we get the answer.

Unfortunately, to understand the limits beyond which we get hurt, first someone has to get hurt, and that's a big part of why we (the nerd folk) still struggle to provide exact answers about where people are safe from all TBI. I do everything I can to protect my scientific volunteers from real injury, but accidents do happen sometimes, and so I want readers to recognize that every time there is a scientific achievement, many people volunteered to go first.

Second, I want people to recognize that sometimes the best stories in military history can be the ones where nobody died. Thanks to the work of these scientists, the beaches of Normandy were scouted and then cleared of ordnance without a single diving-related casualty. It wasn't a miracle and it certainly wasn't because it was a safe job; it was the result of a hell of a lot of hard work. Sometimes, we should also focus on the things that went right.

7. What advice do you have for aspiring authors?

Find the story only you can write. I got my first book contract not by being good - in fact, I now look back on the first few chapters I ever wrote and realize how much I had to learn - but because only I could tell that story. It was literally part of my doctoral dissertation, and they wanted the story, so they had to hire me. From there, I listened to the advice of my agent and editor, and they made me into a better writer. I still hunt for the stories that only I can tell, but that doesn't necessarily mean the stories have to be about or include you. For example, I know that one of my skills is intense archival research, so now I use that to find tales that have been buried.

8. What is your favorite book and why?

I've probably read Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer a million times. I love how his writing style is simple and straightforward; it feels like he's having a conversation with you about the deadly disaster on Mount Everest over a couple of beers, and that makes the book easy to engage with. He tells the story of survival, humanity, and death under brutal conditions without embellishing, and that makes every detail more powerful because you feel like you are focusing on survival rather than feelings along with the mountain climbers as you read. I often try to emulate those principles when I write, and let facts speak for themselves without adding fluff.

9. This book really illuminates both the contributions made, and disparities faced, by women in discovering the science behind diving. Why does that matter?

It wasn't necessarily a goal of mine to highlight the disparities faced by the women, but those disparities were such a constant obstacle to the characters of the story that I realized omitting them would have been participation. However, now that I have more distance from the story, I do think they're important for two reasons. First, those women got their work stolen from them. There's no other way to put it, because a male scientist took their findings and plagiarized them verbatim, then pretended he did the work and took credit. He used that theft to launch himself into a higher position in the military scientific community. At that point, you can see the harm expanding outward from only the women to the active duty military population, because instead of a brilliant, self-sacrificing lead scientist who knew statistics and physics and was willing to literally dislocate their own jaw during repeated seizures to protect military divers, the military community got a lead scientist who was a thief, who never bothered to learn math his entire career, and who developed a reputation for showing up to lab too drunk to function. Who would YOU rather have conducting the experiments to write your safety guidelines? All three of the women involved in these experiments ended up in lower-level positions specifically and provably because their gender was used against them (it's quite blatant in the documentation).

Second, I think it's important to be honest about these types of disparities because they still happen, and they can still have the same negative effects on the end users. I'm a woman in this same field of science, and I've also had male scientists steal my work, lie to me, and get away with it in ways that have hurt my ability to do my job. One time, a duo of male scientists with a track record of problematic sexist behavior deliberately wasted my time getting me to revise and revise and REVISE the same collaborative proposal over and over again for longer than six months, until I found out from a third party that they'd already submitted my idea as their own and gotten it funded. They were overtly lying to me to waste my time so I didn't submit it on my own. Now, they've used that initial foot in the door from using my idea to keep getting funding from the same source on the same topic, even though what they're doing in their experiments now is wildly untethered from any reality of physics or physiology. The amount of funding for this research is finite, and do you think they'll use it to produce any useful guidelines for the military community? These disparities are important to talk about because they were not left behind in the 1940s, and they continue to hurt the end user communities.

10. Your book Chamber Divers is subtitled “The Untold Story of the D-Day Scientists Who Changed Special Operations Forever”, how specifically did they do that?

It helps to set some context here. Remember that at the same time as this story, Jacques Cousteau was tinkering with the first SCUBA regulators when he was living in Nazi-occupied France. Before that, nobody had really done any free-swimming diving. It was all surface-supplied. Giant surface supply boats with pumps, tenders, and umbilicals are hardly appropriate for special operations, at least if you want to live. At the start of WWII, they had some pure-oxygen rebreathers to escape from sunken submarines, but they'd never really been tested properly, which is perhaps why everyone assumed it was safe to use those down to at least 300 feet. Any modern diver now can tell you that 300 feet on pure oxygen is a death sentence. It was during this group's testing of those devices, to see how they could be used in practice and whether they could be used by free-swimming special operations divers, that they discovered the fact that oxygen causes seizures underwater. All of that information traces back to this group, so anyone who has ever donned a LAR V/Mk 25/whatever your MOS calls it owes their safety limits to this lab group during WWII. The link is that direct! They were also the first ones to test oxygen-rich blends on themselves to see if they could allow ordnance divers to go deeper than allowed by pure oxygen, but still rocket to the surface in case of an imminent explosion, so the roots of underwater EOD trace back to this small group of supernerds too.

11. This is your second book that takes place sub-surface. What draws you beneath the water?

I had a cardiac arrhythmia when I was in my early 20s, and underwater was the only place where I felt completely normal. It wasn't a fatal arrhythmia or anything, and it has since gone away, but it made my heart rate go unnaturally high when I was exercising. Underwater, the blood shifts from your legs up into your torso because of the near-zero gravity, and for some reason that made me feel normal, so I would go diving as a workout or just as a break. I also love the way the world gets quiet underwater and you're forced to focus on the stuff immediately in front of you, so I've refused to leave the water ever since.

12. What have I not asked that I should have?

I think you've been pretty thorough, especially because most of my goals with writing are to tell the stories of these amazing people rather than my own. I was a begrudging character in my first book and am thrilled not to be in Chamber Divers at all!

Instead, I'd like to pose my own question: what are the scientific explanations that this community wants? Like I said, writing my first book In the Waves made me realize that we as a scientific community don't always do a perfect job of communicating our work to the people who actually use it, and I like to do what I can to help with that. What other understandable science explainers does the user community want or need from me?

You are NOT helping me reduce my to-read pile!

Into thin air is one of my all time faves, and not as an adventure book.