12 Questions for a Writer: Matt Davenport

Matt Davenport is a veteran, attorney, and historian. He wrote of the WWI “doughboys” fighting at Cantigny in 1918 and now offers a detailed look at San Francisco's 1906 Great Earthquake and Fire.

1. Who are you, what have you written, and why?

I grew up in the Midwest (Missouri and northern Illinois). My mom was a teacher and my father worked in telecommunications. We were fully civilian, but the Army always loomed large--my father served as a soldier in Vietnam, my grandfather was an artilleryman during World War II, and my two great uncles both saw combat in Europe in World War II. My other grandfather and his two brothers all served as sailors in the Pacific in World War II. So it just felt a natural move to serve in the Army Reserves during college and law school, and after my obligation was complete and I found work as a prosecutor then started my own law office, my interest in military history consumed my free time.

As Hollywood and popular history turned more of a focus on World War II, I grew more and more curious about its causes and felt more drawn to World War I, especially America’s involvement which seemed neglected by historians. So it was sometime in 2009 that I was reading Yanks by John S.D. Eisenhower and as I read the chapter “Cantigny,” my interest was piqued. I learned it was our first offensive operation against the German Army, that it was planned by none other than a division operations O-5 who just happened to be George Marshall, and the battle was successful. And the chapter ended, and on the book continued into Belleau Wood and Soissons and St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne. But here was the first U.S. battle and victory against the German Army in a world war and I knew nothing about it.

So I looked for books on it, and the few I found were just not very good--mostly flag-waving, hooray USA nonsense, or self-serving memoirs with a narrow focus. I wanted to know more, so I started research—not the Google kind but actual archival research—and I learned the Battle of Cantigny was the first time U.S. soldiers fought with tanks and modern artillery and airplanes and flamethrowers and machine-gun units. And I said there is a good story here, not just individual stories of sacrifice and heroism by men who would lead our Army in World War II, but our nation’s introduction to combined arms and the birth of our modern Army. So even though I was not a writer, I thought maybe I should write the book I wanted to read about this battle. And off I went.

2. What is it that draws you to writing generally?

There is a story that has not been told and it deserves telling. That’s it. I do not enjoy writing and I am not creative enough to write fiction, though I enjoy a lot of great fiction. I am drawn to nonfiction and in particular history because it is endlessly fascinating to learn what really happened to real people in a former time, whether that was last month or a decade or a century ago.

3. Tell us about the process you undertook to write Over There: The Attack on Cantigny, America’s First Battle for World War I.

I decided early on to shed published, secondary sources and assembled the narrative from archival sources. I went through official reports at the national archives and diaries and letters and unpublished memoirs I was able to get through the First Division Museum and also family members I tracked down through ancestry websites. The most valuable source records I was able to unearth were in the death record files at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis (formerly the Army Records Office where my grandfather worked his entire career). Most death records simply record the date and cause of death and location of burial, but with this battle—and this battle alone—there are much more extensive records because bodies were buried on the battlefield for morale reasons (since units were holding the ground seized for three days and nights, platoon leaders and company commanders ordered the fallen be buried in trenches or shallow graves so soldiers would not have to work and sleep beside their fallen friends). The issue arose postwar in 1919 when the graves registration service tried to locate the remains, forcing them to reach out via mail to former soldiers to ask where soldiers by name were buried. The written responses were often very detailed, telling the story of where a certain platoon or squad was in the court of the attack when that individual was shot by a sniper or killed by a shell blast, and explaining where they were buried along with a map. These responses are all contained in death files—some soldiers’ files contain as many as a dozen written narratives—and provide an unparalleled level of candid eyewitness testimony explaining not just the location and manner of death but the flow of battle and the color of combat. This allowed me to reconstruct this battle in some places yard by yard, minute by minute, soldier by soldier.

4. What did you learn in the process and what surprised you?

The primary thing I learned about writing a work of nonfiction is that you don’t know what you need to know until you begin to try to write about it. Before I began writing, I completed more than three years of research and thought I had a complete grasp of what happened and had a good idea of the structure of the narrative I wanted to build. The day I sat down to write, I did not even get halfway through my first sentence about a morning attack on a trench, I realized I did not know the temperature or the time of sunrise. So I found those in French newspapers and the AEF daily reports by sector. Then by my second sentence I realized I did not know how deep the trench was, and I had to go find it in an engineer’s report. Then I needed to know how the height of the soldier I was following in that first paragraph, which I found in his enlistment paperwork. So the writing process itself was not just trying to write a conversational, forward-moving narrative, but also an additional 18 months of research.

5. Both of your books have been exhaustively researched. You also have a demanding “real job” as an attorney. How do you keep going in the face of that exhaustive research requirement plus “real life”?

I don’t play golf, and from what I can see with other people my age, that saves me countless hours on afternoons and weekends. I also don’t enjoy wasting time and am as efficient as possible with it.

6. What do you want people to take away from this book?

I hope readers turn the final page of the book and are inspired by what we as a nation are capable of when the world needs us. That sounds grandiose, but it is a graspable virtue when you reduce it down to a single soldier. So I wrote the book in a way that readers get to know a few of the soldiers, and if maybe for example they consider how in just a few short months a 22-year-old college dropout from North Carolina or a 26-year-old postal carrier from Kansas is leading men in the dark of night to success on a battlefield against an experienced, professional enemy more than 4,000 miles from home. Then if the reader repeats that story two million times over they can grasp the story of the AEF. And maybe that gives a new appreciation for service in the selfless cause of country, and what we as a nation are capable of when the world needs us.

7. What advice do you have for aspiring authors?

Read good books by good authors. Learn what narrative voice speaks to you. The more you read the better you will write. And when you want to find an agent and publisher, don’t hesitate to reach out to authors you admire. Credit to James McPherson and the late David McCullough for both being kind enough to respond helpfully to me when I was still in the middle of writing my first book. You would be surprised how willing many of them are to help a new writer.

8. What is your favorite book and why?

A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway. I have never read another author who could strip away so much detail and verbiage from a narrative and still paint a transportively vivid picture with the fewest strokes. The story is of course a sad, personal tragedy during the Great War, and his matter-of-fact perspective on combat is devoid of flag-waving or cynicism, just the most eloquent summation of war I’ve seen put to paper: “I was always embarrassed by the words sacred, glorious, and sacrifice, and the expression ‘in vain’. . . I had seen nothing sacred, and the things that were glorious had no glory and the sacrifices were like the stockyards at Chicago if nothing was done with the meat except to bury it.”

9. You’re a North Carolina attorney and an Army vet, so your first book, “First Over There” makes intuitive sense. What is it about the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire that pulled at you enough to demand 75 pages of sources and endnotes?

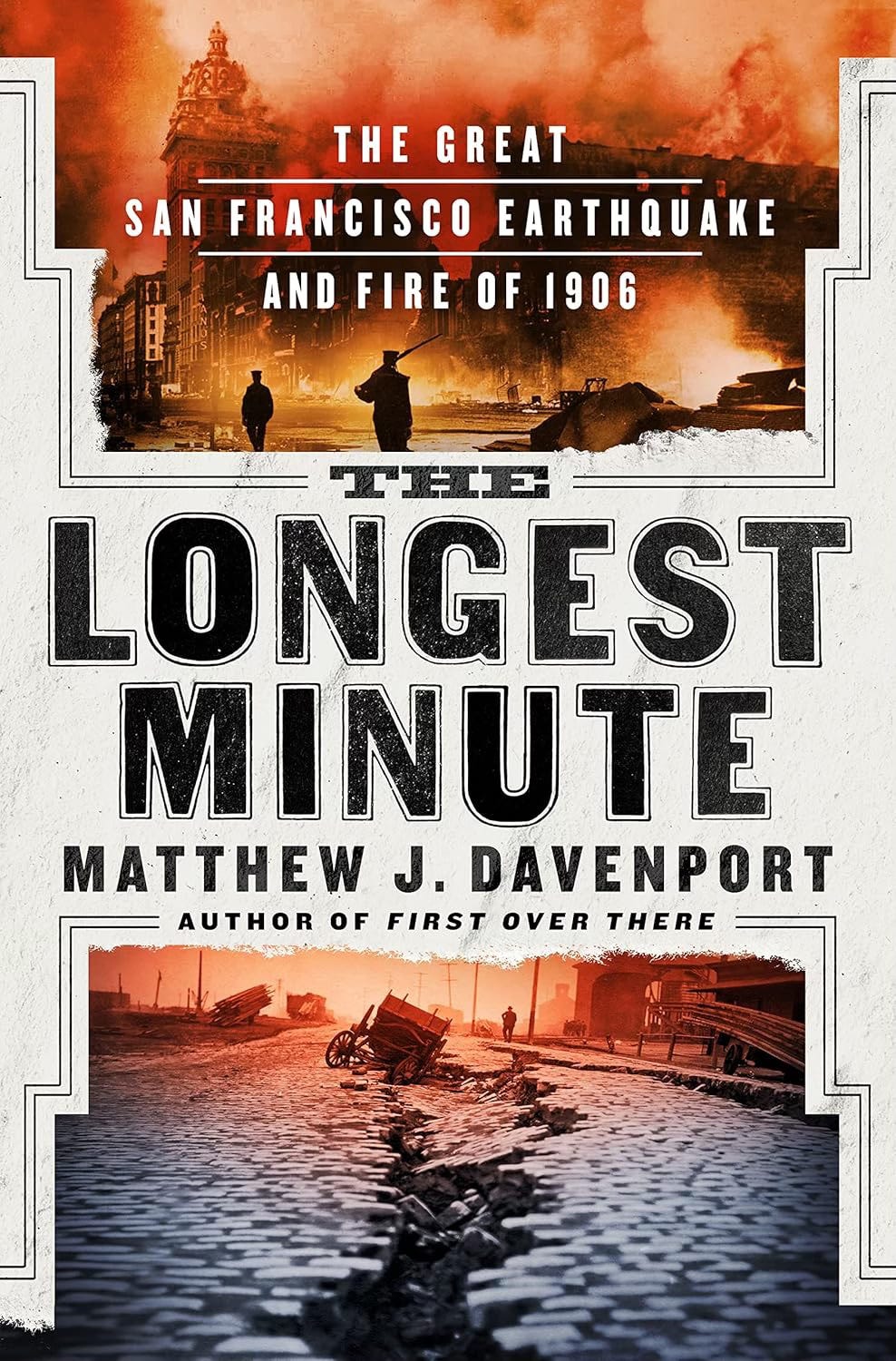

Very much like my first book, it was an event that interested me, and I could not find any books that told the story to answer my questions. I did not know anything about it, so when I learned in a visit to San Francisco in 2012 that the earthquake was followed by three days and three nights of fire and an estimated 3,000 people were killed and most of the city was destroyed, I was riveted. Some books I found told about the science. Some told about the fire. Others told about the people and what they lost. But nothing weaved it all together—how and why did shaking earth destroy a city and kill so many? So I set out to learn that, and then to write the book I wanted to read.

10. The New York Times loved The Longest Minute: The Great San Francisco Earthquake and Fire of 1906, and Publisher’s Weekly gave it a starred review, do kudos like that carry you through the lean, lonely times as a writer or is it gone the next morning?

Researching and writing a story from more than a century ago is a very lonely process. And it takes years (my first took five years and this last one took seven). So at the end when publication day comes, there are inevitably let-downs. There are poorly attended events and bookstores that cancel signings and interviews by people who have not read the book (or even a summary of it). There are “friends” and family who pay lip service to supporting you but then ask weeks and months after its release “Hey is that book of yours done yet?” then condescendingly say they’ll add it to their reading “list,” but never read it while they inhale romance fiction and ghost-written celebrity and reality-TV star memoirs. So when kudos come, they are welcome, and they are a light in the very dark journey. And while the thrill of a good review is fleeting, it can always act as a touchstone—I return to them occasionally to remind myself someone out there read and appreciated the work. So maybe it wasn’t for nothing.

11. Why should anyone read this book?

It is a true story of what really happened to real people who were as alive as we are and had hopes and dreams and ideas for their tomorrows just like we do, but they risked it all just because their nation called. War is not all flags and heroism and victory. Sometimes it is fear and confusion and stress and helplessness. All are part of the story, and knowing the story is true makes it fascinating to learn.

12. What have I not asked that I should have?

I would just add that many aspiring authors of nonfiction or fiction might think that if they get a good agent to take them on and then have the good fortune of signing a deal for a book with a major publisher that all will be great. I thought the same thing. But after two books with a major publisher—and even after a much larger advance for the second book than the first—I was still left doing most of the promotion myself, getting most of the blurbs myself, and it can be draining and deflating. Only if you believe in a story can you see a book through to the finish line, and do not expect a publisher to be there to carry it any further. My own experience has been so disheartening, I probably will not write any more.

You can, and should, read both of Matt’s books. If you want to start with WWI, start here. If natural disasters are your thing, click here.

Just ordered First Over There. Got the other book shortly after publication. Loved his first one, being a history buff. Very much looking forward to this new one. My paternal grandfather served in an artillery unit in WW1. He never spoke of it.