12 Questions for a Writer: Michael Jerome Plunkett

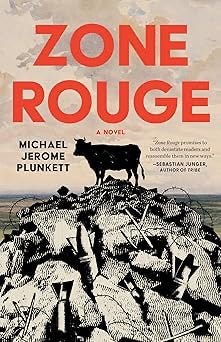

Michael Jerome Plunkett is a book author, magazine writer, podcaster, Marine vet, former EMT, and a founder of the Literature of War Foundation. His new novel, Zone Rouge is more than worth your time.

1. Who are you, what have you written, and why?

Michael Jerome Plunkett, author of the novel Zone Rouge. I am a Marine Corps veteran, and former EMT. I am also co-founder of the Literature of War Foundation and host of The LitWar Podcast. Along with another veteran, I lead the Patrol Base Abbate Book Club.

2. Writing is a solitary pursuit, and I know this book was a long time coming. What is it that kept you moving forward in the writing?

There were seven or eight complete drafts of Zone Rouge over about five years. I never gave up, but I lost interest at times. Writing a novel requires patience and discipline. You are working from a story you have made up in your mind. It’s very bizarre when you think about it. Though writing is solitary, community kept me going; trusted friends gave me bursts of energy just by sitting with the work. I used to be private about my writing to a superstitious level, afraid sharing would taint it, but honestly it’s trust in other people that keeps me going.

3. Tell us about the process you undertook to research, write, and edit Zone Rouge.

I stopped off in Verdun in 2013 because I wanted to see a World War I battlefield. I was backpacking through Europe for the summer, so I planned only to stay there a few hours between trains on my way to Paris. But in that time, I took a short tour of a small part of the battlefield and discovered they were still cleaning up the ordinance from the First World War. They literally told us not to stray from the paved paths because our safety could not be guaranteed past a certain point. I could not believe it. I had so many questions, so many thoughts. But I had a train to catch. So I left and spent the next decade thinking about this little French city that is still cleaning up after the First World War. I knew I wanted to write about it, but I could not figure my way in. It wasn’t until I started experimenting with narrative—creating after-action reports in the voices of what I imagined a démineur might sound like after a long shift—that I found my way in

4. What did you learn in the process, both substantively and personally, and what surprised you?

I learned you don’t need many characters or events to sustain a novel. In early drafts, I’d overcrowded scenes with people just standing there, wasting sentences. One tell I discovered was I found I had characters in the background of a few scenes and they always had their hands in their pockets or arms crossed. Not contributing in any way. Those were the first to go. I cut the cast by half (absorbing or omitting) and didn’t look back.

I also learned to trust the story on the page. Fiction is exploration; if I knew exactly what to say, it wouldn’t take 260 pages to say it. The novel allows space for that exploration, the chance to imagine other perspectives and motivations. The original storyline was much different. But one background character kept pulling my attention away until I realized he was actually the real protagonist. He was secretly struggling with a cancer diagnosis. I wrote that out into a short story just to see where it went. That actually ended up getting published as a standalone short story in Coffee or Die Magazine. That was when I knew I had my novel.

5. Why should anyone read Zone Rouge? If you had a reader in mind as you wrote it, who was it?

Since I began writing this novel five years ago, six major wars have broken out across the world. Ukraine is now the largest minefield in the world. Gaza has the highest number of child amputees in the world. I wouldn’t call the novel anti-war so much as a book about consequences—about people living with damage caused by those they’ll never meet. Verdun isn’t “past”; it’s present.

On the surface, the book is about unstable WWI munitions rising from the soil and the workers tasked with making the land livable. Beneath that, it’s about agency: what one person can control amid pressures they didn’t choose. That mirrors my own life—sobriety, mental health, the discipline of showing up. The work is worth doing. Often it’s one step at a time.

I see a lot of hopelessness among friends and in the country at large. There’s a common attitude that everything is sliding off a cliff. I can’t afford that outlook. When I’ve indulged it in the past, it’s taken me to dark places. I’m a father now to two boys; the stakes are much higher. History suggests the world has always had its ugliness. So the question becomes: what can I contribute today? How do I keep going when others are suffering? I focus on what I can control, sometimes by the minute.

My ideal reader is anyone feeling despair but still committed to the next right task; anyone curious about the quiet labor that follows spectacle. As James Baldwin wrote: “You write in order to change the world, knowing perfectly well that you probably can't, but also knowing that literature is indispensable to the world... The world changes according to the way people see it, and if you alter, even by a millimeter the way people look at reality, then you can change it.”

6. Did you visit the Zone Rouge in the writing? What was that like, and at what point did you realize it would be your debut novel?

After my first visit, I didn’t go back for about ten years. Six drafts into the novel, I hit the limit of my imagination. More than tracing battle lines or grasping the topography of the Zone Rouge, I needed cities, voices, a Tuesday afternoon in a town square. I was writing across cultures; at some point I had to try to feel it firsthand.

One thing I learned early: the Zone Rouge has shrunk considerably since it was first cordoned off after the war. They’re still finding ordnance every day. But beyond the risk of explosions is the chemistry, the way toxins have leached into the soil. Even if every shell fragment were pulled from the earth (and it won’t be), the chemical legacy remains. Gas shells, yes, but even standard high-explosive rounds carried their own mix of arsenic, lead, and more. Those contaminants persist at the cellular level. So while the Zone Rouge may keep shrinking on a map, it’s unlikely to disappear entirely.

7. Many of the characters in this book are carrying a weight, either figuratively or literally. What spoke to you about that notion, and what is your reader to take from it?

This is largely why I chose fiction over some type of non-fiction like investigative journalism or memoir. I could talk about Verdun all day. All the things I’ve learned, all the research, the fun facts, etc. That is not what makes a story though. The reason Verdun stuck with me as a place was because of its potential to attach to so much more than the cost and after effects of war. The connections seem so obvious to me that the initial spark propelled me with enough momentum to get through the first couple without even really knowing anything about the current state of the battlefield or even the battle itself. Sisyphus and his rock, the wider world and its catastrophes, understanding what we can control in our own lives and what is outside of that scope. All of these things jumped out at me immediately.

8. Ending well is hard and I love the ending of Zone Rouge. At what point did you have it in your mind? Was it outlined or did it come to you?

I always knew the book would end with a death. In my fiction, I try to amplify what’s on the page, not to avoid subtlety, but because fiction gives you room to stage things life rarely does. Some early readers have called the novel sad, which I understand, but that wasn’t the intention. Death is a natural part of every life. I wanted to show that even as it arrives, the city keeps moving; neighborhoods change; the places we call home outlast us. That forward momentum, the thrust of time, matters.

Death also adds weight to what Martin has been carrying. I worried he might read as an idea rather than a person, because he endures so much yet keeps going. That’s what I admire in him: the discipline to face what’s in front of him. Hugo LaFleur serves as a counterweight. Annoying and self-important as he is, he has a visible impact (some would even call it positive) on his local community. You may not like him, but you can point to what he’s fixed. Martin’s work is slower, quieter, and largely invisible; its results won’t be evident anytime soon.

In the final pages, I wanted to take his very quiet struggle and turn the volume up. Not into melodrama, but into resonance. Like a choir in a cathedral, hitting a last, held crescendo.

9. What advice do you have for aspiring authors/editors?

Write the book you want to write. Publishing is a notoriously fleeting industry, and the sky is always falling. There’s no guarantee of success, and even if you get it, there’s no guarantee of stability beyond that one book. So figure out why you’re plunging into this in the first place. If you can find even a semblance of why you keep showing up, day after day, putting words on a page no one may ever read, then you’re 90% of the way there, regardless of the outcome. Even if you never publish, you’ll find worth in the work. It has to be about the work.

10. Everyone hates this question, but I persist in asking it: what is your favorite book and why?

Honestly, right now it’s this little 10-page picture book called I Am a Bunny. I think it was published in like 1963 or something. I just became a dad a year ago, and the highlight of my day is getting to read to my older son before bedtime. Something about reading these little picture books over and over again has as much of a calming effect on me as it does on him. It has also given me a surprising amount of insight into how simple an effective story can be. I never realized how much potential these stories had for improvisation, either. The pictures have subtle details that add to the words on the page or sometimes tell an entirely different story. Maybe I’m just losing my mind in the stressful early parenting stage, but I feel like there’s a lot to be taken from these books.

11. With blurbs from Sebastian Junger and Karl Marlantes you should likely be writing another book. What are you working on now?

I’ve got a couple projects tugging at me. One close to my lived experience, the other more historical. After wrapping line edits and copyedits, I’m savoring the first-draft rush: low stakes, sky’s the limit. For now, I get to be weird on the page, wander, and explore until the shape of the next story reveals itself.

12. What have I not asked that I should have?

Why didn’t you just write non-fiction?

I get this question a lot, mostly because the phenomenon of UXO in Verdun is wild and happening right now. But it often smuggles in a hierarchy, which is that nonfiction is superior to fiction. I’m not here to convert anyone, but if I have a hill to die on, it’s this: fiction is worth your time.

Fiction lets us test perspectives and emotions we might never live through. It exercises the “what if,” widens empathy, and sometimes gets closer to emotional truth than a ledger of facts.

And nonfiction isn’t pure, unfiltered “truth” anyway. The moment you put reality on the page, you’re shaping it. You’re choosing a frame, a sequence, an emphasis so it fits a linear narrative. That’s not deceit; it’s craft. But it means any account is, by nature, partial. Think about extreme events. Combat, a car crash, a natural disaster. Two people standing side by side witnessing any of these events can tell honest, completely different stories.

For Zone Rouge, fiction gave me the freedom to honor that complexity without pretending there’s a single authoritative angle. It let me follow the human currents beneath the facts—the boredom, the sudden terror, the maintenance of a life—and build a world where readers can feel the weight of consequence, not just learn about it.

You can purchase copies of Zone Rouge at an independent bookseller or right here. It’s a great read.