LETHAL MINDS JOURNAL

Lethal Minds Volume 10

Volume 10, Edition 1 01APRIL2023

Letter from the Editor

The first time I ever got shot at, I knew it was coming.

I was in the lead vehicle of a five vehicle convoy en route to raid a target based on information that was likely dubious to begin with. The target was in a town in which there were only three ways to enter so if someone wanted to try and kill you, they had a 33% chance of success at successfully establishing an ambush. The best entrance, by which I mean the lone paved road, was usually covered around the clock by Iraqi Police. The night I lost my cherry, they weren’t there.

Scientists place a conservative estimate of how many books I read about reconnaissance patrolling in Vietnam as a teenager at approximately one million. Accordingly, I knew what a suddenly different condition meant. I keyed my radio, pretty calmly actually, “Get ready, there’s no cops at the corner, we’re gonna get hit.”

That was the last thing I did calmly for a bit.

With two surprisingly subdued pops, RPGs flew over the hood of the vehicle behind me, to explode in the desert on the other side. The rattle of RPD machine guns followed. My Marines responded with an overwhelming volume of fire from M4s, M249s, and M240Gs, the booms of a breacher’s shotgun punctuating the crackle of the automatic weapons.

It was over before the .50 cal gunners could crank their turrets around. Some of our fire had been relatively accurate, though we found no bodies or blood trails when we swept the area later. Some of us were less accurate, differing levels of target awareness betrayed by red tracers that had flown into the night sky. Regardless, our immediate action drills were sound, no one failed to lean in on their role, and we broke the ambush. For my own part, the lesson I learned was the importance of taking a breath before opening my mouth and sounding calm when I did. People were listening, keying their own actions from my words.

We’re at a moment when events of great importance are coming at us like those RPGs burning through the air. Earlier in the month, veteran’s social media exploded with concern about a Congressional Budget Office recommendation to means test VA disability payments. As a guy who is deeply thankful for his military pension and disability payments, I will admit I initially had visions of the Bonus Army and a summer spent camped out on the national mall with all of you.

But then I took a breath.

What a lot of the furor revealed is a general lack of knowledge about the roles of various arms of government. We don’t teach civics, the foundation of citizenship, anymore. Perhaps if we did, it would be more commonly understood that the CBO is required to make recommendations, even critically dumb ones the Secretary of Veteran’s Affairs will (and did) starkly reject in a press conference. I am far more concerned about the absence of a budget than I am the CBO version of a “throw away course of action” in developing one. I’m not saying veterans shouldn’t be ever vocal and ever vigilant. The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. But I am saying it’s never the wrong time to take a breath before keying the handset. Especially in a time of instant communications.

That may never be more important than now, the day after a former President has been indicted for the first time in our 246 year history. I’m not sharing my opinions on that, nor am I particularly interested in yours. I am intensely interested in how the citizenry responds, particularly whether our community, who still lead in credibility in national polling, will choose to take a breath and calmly lead, or wildly fire rounds into the sky.

In a world rewarding mindless displays of outrage with clicks and likes, I value calm, measured expressions of opinion based in reasoned thought and well researched and cited information. Where I once took a deep breath before keying a handset, I now take a deep breath before exchanging words.

I believe that’s the example we veterans and current service members should set, surrounded as we are, by deeply unserious people in a deeply serious time. We need not be unified on specific issues to be unified by the notion, often ignored when citing the nation’s founders, that the Republic is bigger than all of us. Its health, or lack thereof, is ultimately a testament to how we Americans spent our time on this spinning orb. For four years or forty, we solved our differences around smoke pits, in boxing rings, or in some cases, beyond the tree line.Then we dusted one another off, slung on a ruck, helped a machine-gunner to his feet, and exited friendly lines as one breathing body.

Whether you’re on the poles of a specific issue, staunchly in the middle, or simply exhausted by the fractiousness of a nation for which we offered to give up our everything, we swore the same oath. That fact, and the way we learned to live together, to die together if need be, is the gift we can still give the nation.

Take a breath and give it. All it takes is all you got.

Submissions are open at lethalmindsjournal@gmail.com.

Fire for Effect.

Russell Worth Parker

Editor in Chief – Lethal Minds Journal

Dedicated to those who serve, those who have served, and those who paid the final price for their country.

Sponsors:

This month’s Journal is brought you to by Fieldseats.com. and the Scuttlebutt Podcast.

Fieldseats.com is an e-commerce federally licensed firearms dealer. They provide virtual reviews on brand new firearms, optics, and gear where at the end of the review they give away the item being reviewed to an attendee!

Currently, they’ve got Reviews up ranging from $20 for a brand new Smith & Wesson M&P Shield 2.0 to $60 for a new Trijicon ACOG with RMR. Each review has limited seating so your chances of winning the giveaway are that much higher!

Check out fieldseats.com to purchase your Reviews and enter to win the item being reviewed and use code “LETHALMINDS” to get 10% off your order. Be sure to also check out their Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube @field_seats for updates on product and other tips and info!

Use code “LETHALMINDS” to receive 10% off your entire purchase at fieldseats.com! Terms and conditions apply.

Be sure to also check out their Instagram and Twitter @field_seats

The Scuttlebutt Podcast is a free podcast and newsletter cover how to help you succeed outside of military service.

Recent episodes include:

23. Rich Jordan on Empowering A Team

41. How to use Chapter 31 Veterans Readiness and Employment benefits with Max

51. What If My Passion Has Nothing To Do With What I'm Doing Now with Bill Kieffer

In This Issue

The World Today

NATO, Autocracy vs. Democracy

Opinion

In Search of a Holistic Approach to Mass Shootings

Book Review - Zinky Boys

Prayers From the Foxhole, Part 2

The Written Word

Worth the Fight

Strength of the Pack

The Standard

Poetry and Art

Justification

Poppies No. 1

War Nostalgia

Transition and Veterans Resources

Object 9: National Home Beer Token

Object 21: Bonus Army

The World Today

In depth analysis and journalism to educate the warfighter on the most important issues around the world today.

Autocracy vs. Democracy, Alliances Picking Teams - Jason Wang

NATO ACT, Communications – Navanti, Account Manager – Johns Hopkins Public Health, Toxicology and Human Risk. Views and opinions in this article represent my own and do not represent any official views of NATO or any other entities.

NATO is adding #31 and #32 – Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, the spokesperson of the 30 countries currently part of the NATO alliance, comments on Finland and Sweden: “I am absolutely confident that both Finland and Sweden will become members of NATO.”

Successful accession is a top priority for NATO, which has established dedicated integration working groups for both countries. Discussions involving President Niinistö (FIN), Prime Minister Kristersson (SWE), General Stoltenberg (NATO), and additional stakeholders are ongoing; several NATO nations and partners have extended bilateral agreements between Finland and Sweden. The Alliance is signalling very clearly: Finland and Sweden will be the 31st and 32nd nations to join the current 30 members of NATO – regardless of which nation is first, they will be at the table during the upcoming NATO Vilnius Summit in July.

The largest military adaptation in Alliance history is underway, developing against this autocratic system – actions taken by Russia, and the rise of China, have raised alarm around the world. Bilateral security agreements, regional alliances, and strategic partnerships are plentiful, often with seemingly contrasting foundations. These preparations highlight the change from a post-WWII concept of East and West, to a new polar alignment: Autocratic vs. Democratic, from the stances of governance, philosophy, and culture – although cultural diversity is the norm, traditions are also here to stay, as the world sees integration across all countries, industries, and sectors. An example – various corporate stakeholders, composed of diverse global investors, proxy interests, and business norms have become increasingly impactful; as military/political alignments are forming, there will be growing pressure to align governance trends, including corporate structure, board oversights, and diversity.

This is not to suggest that NATO membership is without barriers; accession delays involving Turkey and Hungary have been the recent buzz. These complications reinforce the decentralized powers granted to each NATO member, where additional member approvals require a collective, unanimous decision. In the past, alliances have navigated intricate political and military variances between people, languages, and ideologies; this integration will be no different, with NATO representing a collective but democratic system – President Niinistö captures this in a simple statement as it pertains to the Russian invasion: “We can’t forget that if an autocratic system would win somewhere, it never stops.”

Now, digital perceptions and memetic-saturation guide much of global behaviour – with this primer, I share some parting thoughts for you to consider in your own thoughts, analysis, and behaviours, including alignment, interface, and predictions through the near future:

Sustainability: Green-behaviours, industry changes, environmental health risks; planning the future requires both sustainment and changes, both are exploitation risks of growing scale – consider resource balance (energy-mineral comptroller), health governance (medical mandates), and public interest (threat of climate change vs. the why of climate education).

Technology: Global connectivity, information access, infrastructure stability, dependence; the scale of human-technology integration is exponentially accelerating, becoming the most significant domain of exploitation of the modern world – consider subjective objectives (a disinformation majority becomes information), digital enslavement (technology-based livelihood), and the increasing generation of grey technocrats (neutrality as a service).

Situation 1 – Polar Alliances: the US leads, along with NATO and several Asian countries leverage military spending, technical frameworks, and cultural overlaps; this Alliance (1) capitalizes on pre-existing geopolitical frameworks, which currently includes most of the world’s wealth, as well as the highest indices of education, quality of life, health, and safety. It is contrasted by Alliance (2), led by China, along with Russia, with North Korea, Iran, and other autocratic nations; this is supported by existing military and political control interests, with increased focus on resource acquisition, population capitalization, and ideological indoctrination. Digital, proxy, and cultural alignment engagements target both core and non-aligned nations; both Alliances focus on reshaping and capturing cognitive warfare advantages from increasingly connected and utilized benefits of global perceptions portfolios.

Situation 2 – Technocratic-Military Dominance: While economics have long been the dominant global force projector, a hybrid between intelligent technologies and military industrial complexes produces an autocratic-leaning envelopment of existing deterrence-based superpower systems, with the world almost entirely dependent on the resulting automation, supply, and logistics improvements. Technological advancements in population management overwhelm both rule-based law and autocratic-based governance as the popular choice – resulting in an artificial intelligence (AI) mediated co-existence of most countries, with mutual assured destruction (MAD) by larger stakeholders as the deterrence.

Questions for discussion:

What is the benefit-to-risk formula for local populations as the Alliance formations continue? Do country-based alignments still apply in digital culture? What forms from the digitalized interface between these systems derived from democratic and autocratic value?

Consider exponential increases in rate of technical acceleration – is there a clear baseline of technology for future sustainment? Do technological advancements offset sustainability decays? Will there be a clear line, or is sustainment of the future a sliding scale for interpretation?

Opinion

Op Eds and general thought pieces meant to spark conversation and introspection.

In Search of a Holistic Solution to Mass Shootings - Jake Wilamowski

Las Vegas. Newtown. Orlando. Uvalde. From small towns to large, these places should be hitting our news feeds as likely vacation destinations, or not at all. Instead, they’ve been the sites for some of the most horrific mass shootings in history. As the years go on and these events continue, politicians demagogue ever louder for “assault weapons” prohibition, body armor bans, and closing of the “gun show loophole,” among other maladaptive and misguided policy recommendations. But what is really going on here? Will these prescribed solutions from our friends on the left side of the aisle actually have the effects they think?

Seek First to Understand

All too often when we experience problems in our country, eager politicians spring into action professing solutions and demanding measures that will allegedly fix our ails. If we’re lucky, we may get data to back up their prescriptive policies, but sometimes, as is the case with mass shootings and gun violence, the qualifier is simply, “common sense.” Surely, they argue, you can see the connection between guns and gun violence! But before I address that, I’d like to take a step back in our thought process. In our rush to digest the traumatic news of the day and demand resolution, I think we forget to ask, “Why did this happen in the first place?”

Ultimately, these shootings happen for a reason. Trying to understand that reason, as difficult as it may be, is called empathy. To be clear, I’m not talking about sympathy. But like the famous serial killers of the 1970’s and 80’s, we must try to dig in to their minds to find the instigating factors that in one case led an 18-year-old student to shoot up an elementary school, or a millionaire who seemingly had it all to open fire on thousands of concert goers from a 32nd floor hotel window. Just like John Douglas’ work in what would later become the hit TV show Mindhunters, we need experts who work to understand the “why” of these events. Only when we identify the why can we begin to formulate an effective, long-term solution to this problem.

Correlation Does Not Imply Causation

Now we have these events happening (we don’t know why) and we almost immediately become inundated by the numerous proponents for prohibition prescribing that our government disallow private ownership of this firearm or that feature that was involved in the event. Unfortunately, this fails the basic test of correlation versus causation. Let me give you some examples.

An intoxicated adult leaves a bar at 2AM, gets in his car, and while driving home hits and kills someone in a motor vehicle accident. The car and the alcohol are both correlated to the killing. In other words, there is a relationship between the objects and the event. However, that relationship is not causal, meaning that neither the alcohol nor the car caused the killing. It was the intoxicated individual who made the decision to get behind the wheel that we hold responsible. As a society, we’ve correctly concluded to hold the individual responsible for their actions, and this is backed up by miles of legal precedent.

I’ll give you another example. A police officer wrongly shoots an unarmed minority in any town in this country. We don’t blame the firearm, and we hopefully don’t blame the victim. We blame the police officer responsible because he made the decision to pull the trigger, and rightly so. How else could it be?

Only by understanding the differences between correlation and causation can we come to logical and effective solutions to mass shootings. The AR-15 is not a causal factor in mass shootings. They are certainly correlated to shootings just like alcohol is correlated to drunk driving, because you can’t have one without the other. But the weapons in my safe, and in possession by millions of law-abiding people across the country are not like the One Ring, constantly tempting Frodo with dark and corrupting power. Weapons, like all kinds of other objects, are inanimate.

This is an important distinction because it informs how we go about searching for a solution to the problem. Put differently, we don’t want to be placated with politicized platitudes that inevitably prove ineffective. Rather, we need to first understand the problem at its roots, and then we must attack it at the source.

What Does a Holistic Solution Look Like?

I keep coming back to the Columbine shooting in 1999. It was so unexpected and beyond the pale of understanding. In my mind it seems to be the precipitating event that started the trend of school shootings. For some reason, what those two kids did on that fateful day in April has spawned a wildfire of copycat events that continue to this day. We know that we need to study the “why” of these events, and I speculate that mental health plays a large role. In particular, let’s take a look at the policy of deinstitutionalization.

Deinstitutionalization is the name given to the policy of moving severely mentally ill people out of large state institutions and then closing part or all of those institutions. Beginning in the mid 1950’s and reignited again in the 1970’s, it significantly helped contribute to the mental health crisis we see today by discharging people from public psychiatric hospitals without ensuring that they received the medication and rehabilitation services necessary for them to live successfully in the community. Deinstitutionalization further exacerbated the crisis because, once public psychiatric beds had been closed, they were no longer available for the people who would later become mentally ill, and this situation continues to the present day. Consequently, approximately 2.2 million severely mentally ill people do not receive any psychiatric treatment in the United States.

What does this look like today? According to the New York Times, medical experts at Yale University had attempted to treat Adam Lanza in the years before he perpetrated the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School. Specifically, they noted, “severe and deteriorating internalized mental health problems,” later in his life. For one reason or another, it seems that his mother unfortunately neglected to heed their warnings.

But I think this highlights an opportunity for improvement. Parents may not have the time, money, knowledge, skills, or facilities to effectively care for a mentally ill child, and I don’t think this is a fair burden to lay at the feet of family and relatives alone. Rather than offering take-it-or-leave-it medical advice, effective societal support structures for the mentally ill and a dignified approach that destigmatizes mental health treatment may help lead us to more positive outcomes in the future. The key to this approach is it seeks to identify and treat the cause of the issue: mental health.

Note: My interest in improving mental health institutions is not a call for universal healthcare. I’ve seen some individuals in poor faith attempt to shoehorn loosely or even unrelated policies into the answer for mass shootings. I am not interested in commenting on other political issues, only in identifying areas for improvement specific to mass shootings.

Racism is also a seemingly common thread among some portion of mass shooters. As difficult as it may sound, racist individuals must be brought back into the fold of modern society. What do I mean? Well take a look at how social discourse operates today. Social media is used by individuals as well as politically correct corporations to identify racist personalities and push them into the shadows. Removed from contemporary discourse, these uneducated and maligned personalities fester and devolve as they become surrounded by individuals who only agree with them and encourage their dysfunctional thinking. For some, it’s often only a matter of time until they burst back out into society in horrific acts of violence.

How can we begin to address this? Before going into combat, you have to do reconnaissance and intelligence gathering. The more you can understand about your opponent, the better you can counter his moves before he makes them. So when it comes to racist people in our society, I think it’s helpful to try to understand them first.

Soft White Underbelly is an incredible Youtube project run by a man named Mark Laita. Described as interviews and portraits of the human condition, Mark talks to individuals who most would consider to be on the fringes of polite society. Have you ever wondered what a prostitute, a rapist, or a white supremacist has to say? What are their stories? I think Soft White Underbelly is a powerful tool that can help give us a glimpse into the personalities and behavior we’re looking to change.

Take Donny for example. Donny is a skinhead with a background that shouldn’t sound too surprising. Raised in poverty with no parents or role models to mold him, he found the family he needed in the white supremacist movement. His story isn’t terribly dissimilar to so many inner-city kids who find role models and family bonds in an all too idolized gang lifestyle. Drugs also played a significant role in his life; as of the time he was interviewed, Donny was addicted to Fentanyl. And so, we get a portrait of our opponent, in his own words.

What do we do with this information? Can we turn humans like Donny back from the path they’re on? Like Luke Skywalker talking about Darth Vader in Star Wars, we have to believe that there is something good still left in there, something worth saving.

Enter Daryl Davis. Daryl has an incredible story that was detailed during an episode of the Joe Rogan Experience podcast in 2020. In short; Daryl, an African American man from Chicago, is responsible for the reform of over 200 Ku Klux Klan members, including some from the highest levels of that organization. And he did it all by using respect, patience, knowledge, and conversation. Now, I’m not saying we can all go out and be identical versions of Daryl Davis, but I think he’s given us the keys to unlocking successful discourse with our opponents on this problem.

In Daryl’s own words, “If you want to solve this problem of racism, we need to stop focusing on the symptoms… It’s like putting a band aid on cancer. You gotta go down to the bone and treat it at the source, the source of all this is ignorance. Ignorance can be cured. The cure for ignorance is called education. So, you fix the ignorance, there’s nothing to fear, because you fear what you don’t know. If there’s nothing to fear, there’s nothing to hate. If there’s nothing to hate, there’s nothing to destroy. So, we need to focus on the ignorance and we need to address it with exposure and education and conversation. We spend way too much time in this country talking about the other person, talking at the other person, talking past the other person. Why not just spend a little bit of time talking with the other person.”

Daryl Davis is an incredible individual with a powerful attitude, and I think we can all learn a lot from his example.

What Not to Do

Of all the possible solutions to the epidemic of mass shootings, I think mass punishment AKA prohibition is the least informed, the least effective, and has the potential to have the most damaging consequences down the road. Prohibition is the least informed because it puts a band aid on the proverbial bullet wound. It says, “We’re fine with these marginalized people living and working and struggling alone with their demons in our society, as long as they don’t have guns so they can’t bother us.” Quite frankly, this is lazy and shameful thinking as it leaves the least fortunate and most vulnerable among us alone and without support. Again, we must address the cause of the issue, not simply mask its symptoms.

Prohibition will also be an ineffective measure because it runs contrary to the American way of doing business. The fact is, as Americans, we want what we want and have a loose relationship with laws that tell us otherwise. Look at alcohol prohibition 100 years ago. Even at its height, most Americans probably knew where they could go to find a drink. Similarly, I’d bet most people today have tried cannabis products in one form or another, all while marijuana remains classified as a schedule 1 substance by the federal government. In short, making something illegal in no way guarantees it will go away; it will just be another band aid on the problem.

Finally, prohibition is outright dangerous for several reasons. First, it is dangerous because it will make criminals out of millions of law-abiding citizens across the country. The cat is out of the bag. There are an estimated 385 million firearms in private ownership in the US. Were prohibition laws to be passed, a vast majority of law-abiding citizens would not comply, and consequently become felons overnight. This is hardly the desired result of anyone honestly looking to solve the issue of mass shootings in this country.

Additionally, just like the rise of bootleggers, illegal alcohol importers, and organized crime syndicates in the 1920’s, there is no reason to believe something similar wouldn’t occur in the case of firearms prohibition. Mexican drug cartels already operate across the entirety of our southern border and exert complete control across vast swathes of territory in Mexico. Think about where the majority of marijuana in the US comes from. It would only be natural for the cartels to do the same with prohibited firearms. Were prohibition to be enacted, we’d in effect be helping the cartels (perpetrators of drug smuggling, human trafficking, extortion, and murder, among other crimes) by giving them another item to import and sell on our streets. So I think we must root the discussion of prohibition in reality and include these negative externalities; it simply isn’t all sunshine and rainbows.

A Failure of Leadership

Finally, poor political leadership on this issue gives us an opportunity cost component that should be considered. Leaders on the left have a simple strategy, demagoguery and draconian laws, often bracketed by our four-year election cycle. It’s a case of when your only tool is a hammer, all of your problems look like nails. Every four years, liberals use our elections as an attempt to bash through legislation that would restrict the rights of tens of millions of law-abiding Americans while simultaneously failing to address the core of the issue. This lack of leadership has led to the broken record of liberal rhetoric that we see today.

Those on the right have another problem; when mass shootings happen, there is almost no leadership or constructive thought on the issue at all. Conservative rhetoric is reactionary, understandably so to an extent, but fails to generate any unique, thoughtful, or creative solutions to the issue. The call is often to arm teachers or to somehow put good guys with guns in schools. At worst, calls for active shooter training that includes blank fire rounds and flashbangs in elementary schools comes across as absolutely ridiculous. Like liberals, conservative leadership’s failure to address the core of the issue has contributed to the stalemate we’re in today.

What is the opportunity cost of this chicanery? As of February 22nd, the Biden Administration has donated over $75 billion in assistance to Ukraine. How many mental health support facilities could we have bought for $75 billion? To how many underserved and at-risk communities could we have provided outreach and education? Even to band aid the problem, how many security guards could we have purchased to place in schools? Before Russia invaded Ukraine, we had no plan to spend that money. And yet, when the occasion arose, we found a way to make it happen. It’s shameful that we can agree to waste ungodly amounts of money on events outside of the US while allowing our country to fester and rot at home.

How do I know it’s not about guns?

Sue Klebold, mother of Columbine shooter Dylan Klebold, wrote the following in her book, “Dylan and Eric had already been in certain corners heralded as champions for a cause. Tom and I received chilling letters from alienated kids expressing admiration for Dylan and what he’d done. Adults who’d been bullied wrote to tell us they could relate to the boys and their actions. Girls flooded us with love letters. Young men left messages on our answering machine calling Dylan a god, a hero…”

This tells me our society is sick. It seems to me these shootings are an external manifestation of some sort of internal societal neuroses. Banning guns simply doesn’t cut it. Something is deeply, breathtakingly wrong with us. This problem is huge and dynamic and tough, and it’s going to take a lot of hard work to turn things around. I won’t pretend to have all of the answers, but I think we can get there by first trying to ask the right questions. Moving forward, I hope we can avoid easy solutions and black-and-white thinking; we have to put the real work in and find a solution together. It’s the only way we can bring these events to an end.

Book Review - Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War - Eric @ WarMurals

“All of us who were there have a graveyard full of memories.”

- A book review of Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War.

Zinky Boys, the 2015 Nobel Prize Winner for Literature written by Svetlana Alexievich, is a moving and heavy book that provides a glimpse into the human and emotional toll of war, through and account of the Soviet War in Afghanistan. The book is made up of short testimonials from Soviet-Afghanistan veterans (Afgantsi) and their families- each usually no more than 4 pages long. Surprisingly, this was still a fairly difficult to read due to the unflinching look at the costs of war, and I was often only able to get through 5 sections or so before I had to put it down to digest the human and emotional toll. I can only begin to imagine the challenges of coming home and trying to live in an authoritarian society that denies the existence of a war that for 9 years inflicted at least 60,000 casualties on the Soviet military and killed, wounded, and displaced a million Afghans before Soviet troops withdrew in 1989 and the fighting ceased. This chapter of history remains underrated and unappreciated even after American troops began operating at former Soviet bases such as Bagram, Kandahar, and Jalalabad.

Despite being originally published in 1990, the book remains relevant today, especially after Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine, because it deals in the experiences of Russian troops, including the brutal hazing of conscripts, inadequate equipment, and the repressive control of a government that downplays and denies the war's existence .Whereas the bodies of Russians killed in Afghanistan would be shipped home in sealed zinc coffins (hence the name, ‘Zinky Boys’) that were forbidden to be opened and often buried at night, the Russians killed in action today are cremated near the battlefield to hide the true losses from the public.

Zinky Boys is an excellent account of the human experience in difficult times from forgotten voices, and I would recommend it to anyone who, interested in human costs of war, enjoyed the books “The Things They Carried” and “All Quiet on the Western Front.” I would also suggest this book to those closely following the war in Ukraine through sources such as Battles and Beers that provide firsthand accounts of life on the frontline and discuss the strife of the wounded and the families left behind. Additionally, the book offers a glimpse behind Russia's Iron Curtain and into how people live and think in a society and culture that denies its citizens the knowledge that they are paying dearly for a war in blood and treasure.

Overall, Zinky Boys is a must-read for anyone looking to understand the lasting impact of war on those who fight and the communities they return to. It is a reminder of the importance of recognizing the human cost of conflict, regardless of which side you are on. To get a taste of the book, you can read through some excerpts[Here]

Prayers From the Foxhole: Part 2 -Katherine Dexter

Faith used to be a familiar concept. It was harped upon throughout my childhood and adolescence. It was used to guilt me into places I never should have been. “If I had enough faith…” was and still is a familiar phrase. In most Christian religions faith is an essential component to belief in the system. Most would define it as “a belief in things hoped for but not seen”. It was only as an adult that I realized the religion of my youth had to redefine faith in order to succeed.

It doesn’t matter what background you come from, deconstructing your belief system is not an easy or exciting task. It is consumed by anxiety, wondering what comes next, and questioning the authenticity of some of your most intimate experiences. When I began actively deconstructing my beliefs after a lifetime of Mormonism, I felt like I was spiraling. I grew up in a devout home. We read scriptures together every morning. We prayed before the family went their separate ways, and again at night before bed. We were encouraged as children to say our own prayers and read the bible as well as the esoteric LDS scripture on our own. When I turned 8 I was baptized, told that all my sins were washed away, and I would then take upon me Christ’s name and be responsible for all my sins from that day forward. I attended three hours of Sunday service, and a youth activity each week. When I entered high school I began our church’s early morning seminary classes and would participate in an hour long class of scripture study each day before school, then sometimes two youth activities each week, in addition to the Sunday service. My family made it clear that church came before everything. No extracurriculars, and no personal desires, could trump a single meeting.

I was as devout as I was expected to be. I wore my skirts and shorts no more than 4 finger lengths above the knee. My sleeves covered my shoulders, my necklines reached high up to my collarbone, my ears had just one piercing, my hair could not be dyed, and my mother was constantly in a state of shushing my uncomfortably loud voice. I prayed, I read, I gave my tithes, I took the sacrament each Sunday, and I hoped for things that I could not see. When I graduated high school, I went to BYU’s Idaho campus. For members of the Mormon church, they subsidize tuition with tithing money, and even with the scholarships I had been awarded at other schools, nobody could compete with the price of tuition at the Mormon God’s college. It is worth mentioning that there are ecclesiastical interviews for students at BYU, because the college is private and owned by the Mormon church, that assess how willing you are to follow the rules of the campus. Rules which are even more strict than the standards Mormons ascribe to exaltation. During my time there I was warned on more than one occasion that my skirt was too short, and was distracting from the gospel lesson I was asked to teach during a Sunday service. Men were not allowed to have beards, so the 70’s Porn-Stache was edgy and popular. Women were not allowed to wear skirts above knee length, no one was allowed to wear shorts or flip flops, even to the gym. Leggings were absolutely forbidden. If you were caught drinking alcohol, or had a member of the opposite sex in your apartment past curfew, your roommates could tattle on you to the Honor Office (an actual disciplinary entity on campus) and this could result in an investigation and academic consequences. And we’d all signed the agreement to say we would abide by these rules. In the name of professionalism and education sanctioned by the God that Mormons knew was superior to all other Gods, if only by His strictness.

I can pinpoint a few moments in my lifetime of belief where I started noticing the chips in the paint. This was one. I’d grown up in Alabama, far away from the bubble of Utah Mormons, so I’d heard regularly how people thought we were like a cult. I never understood it until I was at BYU, and I finally began experiencing consequences for disagreeing with a system that seemed oppressive and unreasonable. By the time I enlisted in the Marine Corps I was ready to give up the cult of Joseph Smith, I just wasn’t ready to confront why. I suspended my beliefs, I put my questions on the shelf, and decided that comfort was more important than truth. It was years down the line, in the aftermath of a failed marriage, that the shelf finally broke.

There were a lot of very intimate particulars in the destruction of my faith, some that were personal between me and the God I don’t quite understand, and others between me and a religion that I understood too well. When I was 13 years old, I went to a church youth camp in the summer. There was an obstacle course built high off the ground that included a few platforms atop telephone poles you had to jump across. They were placed uncomfortably far apart for my 13-year-old legs, and they called it the leap of faith. Our youth leaders used it in the most obvious way, making us dig deep to find Jesus 30 feet in the air. I remember the way my stomach dropped and I halted. I remembered it every time I jumped from a cliff into water, from the top of the repelling wall in boot camp, from the diving board during swim qual, bounding from mound to mound with live rounds on a range in Marine Combat Training. I remember the way my stomach dropped and I needed to hope that my feet would find sure footing even though I could not feel it. And when I no longer had a belief that God was who I had been told he was, I jumped again, and my stomach dropped, and where hope had been there was a chasm. When I talk about deconstruction what I really mean is the jump with no end, and the willingness to find what is at the bottom, even if there is no bottom.

After taking the leap I realized that I could finally ask the questions I had been told all my youth and young adult years to never ask. Questions about Joseph Smith, about the Book of Mormon, about Jesus and how the bible was written. I decided that if the truth were the truth, it would hold up under any heat. I’d already jumped, so if it didn’t hold up, I let it go. And I distilled everything down into the singular points that I could start over from. I knew there was a God, but I didn’t know what it was, and I wasn’t even sure it mattered. I also knew that I was no longer limited by the Christian version of God, but there were thousands of ideas I could explore. Where religion and faith had once been a tool of control, they became tools of education, and the reconstruction could begin.

The Written Word

Fiction and Nonfiction written by servicemen and veterans.

Worth The Fight - Tim Morrison

I didn’t even know we had been shot at until after the flight was over. I was the medic in the second aircraft of a two-ship formation, flying over southern Syria. We were on our way to Hasakah after picking up a couple of kids, the children of an important SDF general, who had been injured by an old Russian mine. We took surface-to-air fire, apparently. We popped some flares, sped up a little. I don’t know, I wasn’t paying attention. We survived and carried on. That flight, being shot at–it didn’t bother me. The half dead kid on the litter didn’t bother me. It was the days and weeks and months of being told, “Keep on your toes: we have intel that ISIS or the IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps) are amassing for an attack,” that bothered me. It was the waiting that wore on my soul.

One night, at about 0300, the crackle of AK fire, a rattling PKM, and the pop-whoosh-BANG of RPGs broke the quiet. We ran out of our CHUs, rifles in hand, headed for the TOC. We met the Operators, already in their kit, and headed down to the gate. No one knew what was happening. I was terrified, but ultimately relieved that the fight we had been told to expect was finally here. Suddenly, I wasn’t scared. Nothing mattered. No visions of grandeur. No fear. No boredom. There was nothing but that moment. A gorgeous moment of clarity. The purest moment of my life.

It ended as soon as it came. The word came down that this was not an attack. No, this was poor communication from the SDF who were conducting a night range. Starting at 0300 in the morning. They hadn’t let anyone, including the operators with whom they worked, know that this was their plan.

I didn’t sleep well that night. I kept thinking about those few brief moments of clarity, and how free I had felt. Free from anxiety and fear. This may have been the first moment where I recognized how anxious I had been for the past several months. I didn’t know what to do with that realization, so I suppressed it. I forced myself to carry on. I had a job to do after all. I couldn’t take the time to recognize the fear. To acknowledge it was to let it control me.

For nine months this was my life: wake up, make coffee and oatmeal, go meet up with the other medics, ignore the fear, go to the gym, watch HGTV, ignore the fear, smoke cigars, play spades, talk to my wife, ignore the fear, go to bed. Ignore the fear. Ignore the fear. Ignore the fear… Do I have cancer? Soldiers are more prone to it… what is this lump in my throat? Why do my balls hurt? Why can’t I get motivated to do anything? Am I losing weight too fast? Fuck. Fuck! What is wrong with me? Someone tell me I’m okay! But don’t let anyone know something is wrong. They won’t trust you anymore. They’ll send you away. Don’t let them send you away. Don’t be a quitter. There’s only two months till we go home. Everything will get better when we get home.

I came home in January. I came home to a new state, a new house. I got involved in rugby to make new friends. Got a new job. I felt happy. Syria, the war, that nothing of a war, was far away. It was over. My anxiety could stop now. I was home. There was no one here to hurt me, but still it persisted.

For over six months it was a quiet annoyance in the back of my mind. A transient question of, “Am I okay?” Then, suddenly, I couldn’t sleep. Couldn’t eat. I spent days curled up on the couch. The only place I could sleep was on that couch, in the daylight, my head on my wife’s lap. No amount of Benadryl or melatonin could help me sleep through the night. I asked her over and over and over if I was okay. “Of course,” she’d answer. I couldn’t trust that though. Of course she’d say I was okay, she was my wife. But she couldn’t see inside of me. She couldn’t see the disease that I had in my body. This insidious cancer. Even the doctors who had examined me couldn’t see it. They didn’t look hard enough. I knew it was there. There was no other explanation for those little symptoms I was experiencing. I was massively depressed because I was going to die because they wouldn’t find out what’s wrong with me in time.

They call it cyclical thought. It’s a sign of a downward spiral in your mental health. I was in the middle of a downward spiral that would take me lower than I had ever been. I was never suicidal, but now I understood how people could be driven to suicide. Driven to just end their suffering. Driven to end the constant voice in their head. This was no way to live. After a month, I finally got up the nerve to seek therapy. I found a therapist through Psychology Today. He didn’t accept Tricare, so I paid out of pocket. All for the better anyway, I don’t want anyone to know I saw a therapist.

My first sessions were promising. He was a Vietnam veteran. We joked about hearing loss: his from bombs, mine from a helicopter. We met once a week and worked on exercises to increase my resilience. Breathing, and guided meditation. We never discussed why I had this anxiety, just how to manage it when it came up.

In September, I went out of town. I was gone for three weeks, training in San Antonio for Flight Paramedic Recertification. We were still in the first year of the COVID pandemic, so classes were held online. I was alone for two straight weeks. Near the end of this time, my anxiety was at an all-time high. I couldn’t sleep in the bed, so I slept on the couch in my hotel room. I woke up in the night and tried to go on a walk or two, maybe get a workout in the little hotel gym. Nothing helped. I reached out to my therapist and made a virtual appointment.

On the day of my appointment, I told him what I had been experiencing. He asked if I had been doing my breathing and meditation exercises. I had not. His response was, “Well, if you’re not doing those things, I can’t help you.” It was the last time I saw him.

When I came home from San Antonio, my wife had finally had enough. Frankly, I had had enough. We made an appointment to see my doctor to discuss getting on medication. I had avoided medication for almost a year, because as a flight medic or like anyone on flight status, medication would ground me. My doctor was polite, listening intently as I told him all the things that I had been experiencing. He prescribed Zoloft, a SSRI. He told me it would take about six weeks to fully take effect. At the end of our meeting, he told me that I likely had PTSD. I can’t have PTSD; I didn’t see any real combat. I got shot at maybe three times total, and those were surface-to-air fire. I didn’t even know it had occurred until it was over. Either way, his diagnosis remained the same. “I think you have PTSD.”

I sought a new therapist. One of the first things she told me was that my previous therapist was likely using the wrong tools for me. She told me that in the middle of an anxiety attack, it is almost impossible for us to calm ourselves down through breathing exercises. Our bodies don’t work that way. To become “myself” again, we would have to address the root causes of my anxiety, not simply manage the symptoms. We met every other week. We talked about waiting around for an attack that never came and we talked about traumatic experiences in my past. We talked about ten years of EMS work and learned coping mechanisms that were not helpful. We talked about overactive imaginations and how the mind plays its tricks. We talked about the fear I felt in Syria and how, because I couldn’t address or show that fear at the time, it manifested as extreme health anxiety.

As time went on, the medicine worked, and my therapist and I worked on positive coping mechanisms. With the clarity of understanding came the ability to control my thoughts. It had been over a year since the anxiety began to manifest itself outwardly, and I was finally getting better.

For a long time, I didn’t feel like I had a right to have a diagnosis like PTSD. I worried that because my war was not Fallujah or the Korengal Valley, I didn’t have the right to consider that my time overseas caused my anxiety. It’s the, “Yeah, but so and so had it worse,” mentality that is so prevalent in public service and military communities. Trauma comes in many forms. It comes from being shot at too many times, or from seeing too much death, too much destruction. Sometimes, it comes from months and months and months of waiting for a fight that never occurs.

I don’t have some profound closing statement and my story is anything but exciting. I wrote this to remind myself, more than anything, that trauma doesn’t have to come from the grand battle, and the days of life and death. Certainly those things are traumatic, but for me, and for many others, the trauma is in the waiting. If we are going to help ourselves and our fellow servicemembers, we must be open about the things beyond the fight that cause us to struggle with mental health. We must be open to understanding, and we must be willing to set aside our preconceived notions of what is or what isn’t traumatic.

I still wonder if there are others like me out in this world, people who didn’t experience the war in the way that they thought they would, yet still came home and struggled. If you are reading this, and you are one of those people, I want to tell you that your mental health is no less important than the Korengal veterans. Your service still has meaning, even if it wasn’t in the way you thought it would. You are worthy of living a happy and healthy life. You just have to be willing to fight for yourself. You are worth the fight.

Strength Of the Pack - Jaime Lima

Being an only child, and an extrovert, has always placed the mantle of belonging front and center. I was born in Panama, and while my childhood was a happy one, I never really felt like I belonged. That changed when I moved to the US. Even with the challenges of being an undocumented immigrant from age 14 to 20, for the first time ever, I felt I was getting close to being accepted by who I am. When my time in high school came to an end, that sense of belonging came to a halt. My friends moved on with their lives, while I lived in my grandparent’s basement and worked jobs that would pay me under the table. That old childhood question came back; where do I belong?

I joined the US Marines back in 2003, when I was 23 years old. After Boot Camp and School of Infantry, I got orders to beautiful 29 Palms, California, to become a part of 3rd Battalion, 4th Marine Regiment. I deployed with my fellow Marines, my brothers, some whom I had known since Boot Camp, three times to Iraq. This was unusual, being together for so long, and from the very beginning. I was together with my friends, until it was time for us to go our separate ways toward the end of our fourth year. Some guys got out of the service; some re-enlisted and were sent away to their new units. Out of my core group of friends, I was the last one left. There was no ceremonial farewell, but it was cool. I was very busy training to prepare for Marine Special Operations Command Selection and Assessment, the first step in becoming a Special Operations Marine, a Marine Raider.

I made it. I got into the cool guy action club. “No more micromanagement (so I thought), jumping out of planes and helicopters, cool new gear and guns, awesome training, and going to countries where I could grow my hair out”. Training was hard, but very rewarding. Everyone that was there, really wanted to be there. Being part of a Marine Special Operations Team was the place to be. After some deployments and other work overseas, I was given orders to serve as an instructor at the Marine Raider Training Center. This is where Marines who have been selected are trained and ultimately earn the title of Marine Raider.

I was feeling pretty great about life in general. I was happily married, we were living in our first new home as a married couple, in a neighborhood where some of my best friends lived. I was looking forward to actually seeing my wife most days, as being at the Training Center meant that I wasn’t going to get deployed for a while. Life was good. I would look in the mirror and go “Tall, dark, handsome, and an action guy! Honey, go tell your friends how lucky you are!”. Did I mention humble too?

The Training Center was super busy. As Marines, we conducted a lot of training in the water. In my particular section at work, we had a need for a MCIWS, an acronymic title which stands for Marine Corps Instructor of Water Survival. I knew the course was hard, and I was lined up to attend. It has a bit over a 50% washout rate if memory serves right, and I was not the best swimmer. With the help of some of my peers from my section at work, my swim time had gotten a lot faster, and based on my track record of passing every training course I had ever been sent to, I was confident I would perform just fine.

I was not ready. The training was like underwater assault. Class instructors bellowed “Swim with your uniform and boots on, take them off on the deep end, now swim some more. Tread water with this brick. Give it to your buddy, but keep both hands out of the water. Ok, time for rescues! Half of you are the victims, go put that flak jacket, helmet and rubber rifle on. As the rescuer gets closer, splash water at his face. Once he is close enough, jump on him and take him underwater with you. Rescuer, do the appropriate pressure point technique on the victim, get him off you. Now bring him above water, and do the appropriate rescue technique like we showed you. Good, good, and now do it again fucker!” There was a lot more, I just kept on going until the training day was done.

As the mythos of Marines go, we never quit. But as a Raider, you should rather die before you quit. We were practicing one of the rescues, and as I was half way through, pushing the victim towards the opposite side of the pool, I just somehow couldn’t push anymore. My legs felt like they were stone, and I couldn’t slow my breath. I couldn’t slow my heart rate. I just couldn’t do it, and I didn’t understand why. (Later, I figured out it was a panic attack) Unable to contextualize what was happening…I started to sink. Right before I got to the bottom of the pool, one of the instructors swims down and pulls me out.

He is yelling; “Just quit, just get out and quit! What are you even doing here? Just quit! Get out!”

To civilians that might sound harsh, but he is good at his job, and he was doing it well that day. Remember, this is the Marine Corps, and there were not going to be any kind words after he pulled me from the bottom of the pool.

I did get out of the water, angry at myself. Feeling a deep shame for not performing the way I’m used to performing. I didn’t feel like myself…. I walked towards an old metal bell hanging next to the pool, the one you ring to announce you have had enough. This particular MCIWS school in Camp Lejeune had one. My heart was racing, I was grinding my teeth, listening to the instructor still yelling for me to quit, as I would be a liability if I was to somehow pass this course. I also heard the voices of some of my classmates yelling for me not to do it. I then hit the bell as hard as I could.

A minute later I’m inside the locker room, warm water running down my head in the shower. The Chief Instructor walked in to check on me. I told him I was fine. Of course, I wasn’t. My heart started to slow down, I stopped shaking, and I asked myself, “you idiot, what have you done?!” I started regaining my breath, but I also felt dizzy. I sat down on a bench; wondering if there was any way that I could get back into the pool and rejoin training. No, I could not. I got dressed and gathered my things, and realized I had to go back to the Training Center, and explain what happened. I froze for what seemed like a few minutes, but in reality, it was half an hour. I just sat there.

As I walked out of the building, one of the Gunnery Sergeants from my section was there. I couldn’t swallow. My heart raced. He asked what happened. I went over what I just experienced; he then said to me “I’m going to send you again”. I didn’t know that it was possible to feel terrified, devastated, and deeply grateful all at once. A chance at redemption had already materialized.

As I drove back to my office, I started thinking how much trouble I was going to be in with my leadership. Will they try to get rid of me? Has that even happened before? What would I do? This was who I am. This was my identity. I didn’t want to get pulled from my pack.

I sat at my boss’s office, and he asked me what happened. He says to me “We are not supposed to quit”. I wanted the Earth to swallow me whole. I could see in his face he felt bad for me, and somehow I felt worse because he was not yelling at me instead.

I got to my little office cubicle. One of my buddies comes out and asks me if I’m ok. I say yes. He smiles at me, and he walks away. He and a handful of other dudes there would treat me like I still belonged. I don’t know what I would have done without them. This was not the case with everyone else. At first, I was too busy beating myself up and feeling sorry for myself, but eventually I noticed that other guys in the section were just not engaging with me.

Something had changed. Then there were the passive aggressive comments, overheard conversations with dudes from other sections in the Training Center about me; discussing with my peers how I didn’t belong there. As the days went by, it got worse. There were some peers who thought I no longer needed to be in the unit. It never dawned on me that it would be this way. All along I thought my command, the senior leadership, would want to get rid of me, but it was some of my peers who were talking about how embarrassed the unit as a whole was, because having a quitter among them makes everyone lose credibility.

The days at home were long after work. I was unable to leave my heartache at the office. I started to drink more than usual. I was mostly a weekend drinker back then, but then I just lay on the couch, staring at the TV. My dog Alex, and my pet pig, Napoleon Bonapig, joined me for a snuggle. I have sometimes wondered how much worse I would have felt, had it not been for my loving pets.

I was miserable at work. I was miserable at home. My wife didn’t know how to help me. I wasn’t honest with her about how tormented I felt. Weeks go by, and every time I thought I was getting over it, someone in my section brought it up, or shared a snarky comment. “So and so just passed MCIWS. Not surprised, he’s not a little bitch”. I pretended it did not bother me. I had a funny drawing by my desk, taped on the side of my cubicle. It was a Mr T looking guy riding a warthog. A hog rider if you may. It always made me smile. Someone wrote “I quit” under it. I took it down.

But all during this, I was swimming every day. That same Gunny that met me at the pool when I quit, handed me a 25lb bumper plate weight and told me, “You are going to swim with this from one end of the pool to the other. This will make your legs strong. Do a few laps at first, and once you get the hang of it, do it more. Once you start getting tired, do more”. He never made me feel small. To this day I’m grateful for him. I swam with his stupid bumper plate, and as the days went by, I could do laps with it. I did it in my dreams. I woke up in the middle of the night sweating, sometimes even holding my breath. I went to MCIWS again. This time I passed. I felt invincible again! Yes, I’m back! On that day, my wife tells me that she is pregnant. I thought to myself, “hang on to this feeling for as long as you can”.

The feeling wouldn’t last. Nothing changed at work. There were less snarky, passive aggressive comments, but I was never treated the same by some of my peers the way it was before. I hated everything, but above all, I hated myself.

I started thinking that it was time for me to leave the service. As I explored that thought, I reached out to my cousin, who was working at a cool new company. One of his colleagues was a previous MARSOC Marine. This guy was in charge of a department there, and my cousin said he would talk to him about me, and see if a job opportunity was available. My cousin called me back. He told me that his guy called someone from the Training Center, and he said nothing but bad things about me. I went silent on the phone. I hung up. I was angry; not only did someone not want me in the unit, but they decided to go out of their way to close the door for me on an opportunity out in the real world. I can only imagine what that convo must have been like: “Oh, you mean Lima? He can’t swim, and he is a quitter! What business are you in? Manufacturing? Yeah, well, like I said, you’re better off without him”.

All my years of training, the multiple deployments, and this moment in the pool is going to define me?

Band of Brothers my ass! You are not only messing with me; you are also messing in the way in which I provide for my family! You coward! Who are you?! I sat down, and thought to myself, maybe I’ll go for a swim out in the Atlantic Ocean, about ten minutes from my house. Maybe I would swim out there without the intention of coming back. I then remembered my wife was pregnant with our first son. I started to cry

As my wife and I discussed whether I am going to reenlist or not, it felt surreal. I always thought I would be in the service for twenty plus years, but instead, there I was, considering leaving everything I know, and what makes me, me, behind. We decided I would leave once my contract was done.

The last few months of my service I was on autopilot. But I did my best to help anyone who might be struggling with training at the pool. If I could get at least one of those guys not to panic in the water, I felt I was doing my job.

One day, as I just get done working in the pool, one of our senior enlisted leaders, a Master Sergeant, approached me, and told me something that made me feel like I was worth wearing the uniform,

“It’s too easy to kick someone when they’re down, I’ve been there and had someone pull me out of a low point. Some of these guys I’ve known for a while. They don’t fool me because I know their history. Trust me, the ones that shun you or cast doubt have their own shortcomings. Attacking you, it’s their way of deflecting”.

Those words restored me…I felt like I mattered. I no longer felt the need to swim into the ocean. I should tell him that someday.

On my last day in the Marine Corps, I went to pick up my DD214, which is the document that summarizes my service. Once it’s in your hands, you are done.

The guys in my section were busy working in the pool. I went to say goodbye to the few that cared. One of them asked for a favor. If I could drive the bus with the students back to the barracks. I was not wearing my uniform, just jeans and a t-shirt. I got the students on the bus, and drove them to their barracks. I laughed, thinking to myself, millions of dollars and thousands of hours spent on my training, and on my last day as a Marine, the last thing I do is drive this bus.

And just as I left my first unit, nobody really said goodbye. There was no ceremonial farewell, just a little thank you plaque from my boss, who handed it to me himself. I visited the memorial of our fallen outside of our command’s headquarters building, and I paid my respects.

I got in my truck and tried to leave the man I was behind. With my wife waiting for me in Idaho by then, I started the drive out of NC. I start to wonder, what kind of father will I be? My son is due in four days. What will I do for work? I had an interview in Boise, but it was not guaranteed that I would get the job. Where would I belong? And then I told myself a quote that you will find around the Training Center. “All it takes, it’s all you got”.

The Standard - George Bednar

Reigning in concealed anger, he grabbed the page out of my hand to look. “It’s not a big deal, Gunnery Sergeant, you just missed the ‘J’ in his name.” Following a deep inhale and exhale, he walked out of the room to his office. He would fix the letter, rescan the document, and have me sign it again. He was furious. Not with me, but with himself. His frustration was caused by a minute, harmless error that most would brush off. Not Gunnery Sergeant Daniel Triebell. He forgot a single letter in a one-hundred-plus page commissioning document that was organized with attention to every detail. It was not “okay”. I will never forget this moment of unwavering commitment to do the little things with precision and set the standard for others to follow.

GySgt Triebell is the epitome of a Staff Noncommissioned Officer in the Marine Corps. He is the Assistant Marine Officer Instructor (AMOI) at the Notre Dame Naval ROTC unit in South Bend, Indiana. He is the example to follow in all facets of his Marine Corps career. Rarely dishing out compliments, my father noted that GySgt Triebell’s dress blues and MARPAT camouflage uniform “appear painted on” his lethal, warrior physique. He IS the standard when it comes to appearance. His military tuck is perfect, his camouflage sleeves are rolled with precision, and his dress shoes shine so bright they could blind the enemy!

Although physical appearance is a priority for Marines, leadership is not about ribbons or large biceps protruding from one’s uniform. Leadership is about taking care of people and nobody understands this better than GySgt Triebell. This past December our unit took in a 2ndLt for a brief period. He just finished The Basic School (TBS) and was waiting to begin flight school. When I asked GySgt Triebell how this 2ndLt ended up at Notre Dame, he replied, “He wanted to spend some time at home near his family. It is my duty to show him what it means to take care of officers so that he might one day care for his enlisted Marines.” I was in awe. He did not invite the Lieutenant to help him with paperwork, he worked to get him to the unit so that his future enlisted Marines might reap the benefits in the future.

GySgt Triebell has children, a mortgage, an arduous job, and plenty of other things to deal with. Despite this, a few weeks ago, he brought me and a fellow senior to a coffee shop to discuss leadership. He bought the coffee. He even brought notes because “[I] always need to be ready.” We sat for hours talking about how to properly delegate tasks, when to be vocal with a platoon, and above all, about the importance of taking care of enlisted Marines. When I thanked him for his time he replied: “It’s my return on investment that you are all successful.” He did not get an award for his time or recognition from his superiors, he wanted to be there with us. We will never forget it.

Every year Notre Dame puts on a national Naval Leadership Weekend (NLW) conference. The guests are frequently high-ranking service members and units from across the country travel to South Bend, Indiana for the event. It is a big deal. Although it did not fall on his plate, GySgt Triebell was the master orchestrator. He took initiative. All six of the main event speakers came because of his work and, in my four years here, there has never been a greater lineup of talks. After the final speaker I checked my phone and a text awaited me: “I don’t miss!” No you don’t, GySgt!

Although the buck stops with the leader, GySgt Triebell is never satisfied. While many Marines view their “B-billet” as a time to relax and recover before they return to the fleet, GySgt Triebell is still operating in peak form. He was able to get both General Mattis and Medal of Honor recipient Kyle Carpenter to speak with our unit privately. Seldom could a unit get one of those distinguished men to talk with them about leadership. He got both. It was not allure or recognition he sought, it was impact. GySgt Triebell is solely focused on his mission: making the best Navy and Marine officers on the planet. He is willing to move mountains to ensure the mission is accomplished.

This summer I finished Marine Corps Officer Candidates School (OCS) in Quantico, Virginia. My friends, family, and peers asked me: “What was your biggest takeaway? What was the hardest part?” The answer is simple: after interacting with elite enlisted Marines like GySgt Triebell for the last four years, I recognize the challenge of the journey that awaits me. When I raise my right hand this May and commission as a Marine Corps officer, I will be leading the most hungry, skilled, and lethal people in the world. GySgt Triebell sets the standard for others to follow. His leadership is unfaltering and represents everything the Marine Corps seeks in its ranks.

Poetry and Art

Poetry and art from the warfighting community.

Justification - Douglas Patteson

I've never been to the killing field

They need our support

Though I contributed to it from afar

It's just imagery ok? Send it

I stepped through that door boldly

If you can't, I'll get someone who can

And the aftermath left my soul ajar

It's a proxy war

But do the dead care who the proxies are? Did they even know?

Poppies No. 1 - Eli Gardner

All of us know the shape of a poppy

All of us know multiple indicators

To positively ID an IED.

We know enemy tactics

And the orientation of a mosque.

But do any of us know

How to fill out a travel voucher

Or how to catch Finance in the office.

War Nostalgia -Eli Gardner

Why are we nostalgic about war.

The civilians who live through it

Do not share this feeling after all.

The soldiers who fight it think bittersweet thoughts.

That familiar arsenic-ambrosia mixture.

We went away when we were young.

We went away half formed.

We thought we knew everything.

We thought we were immortal.

We thought the enemy was just the enemy

Faceless and full of blame.

But when you see your first death

When you lose your first friend

When you hear the sounds of bombs

Or the high-pitched scream of mortars

When the alarms on base cry out

Because there is death enroute

When you attend your first ramp ceremony

And a flag-draped coffin passes by you

Suddenly you grow up a little.

Suddenly your immortality vanishes.

Suddenly you realize no one back home will understand

Quite like the brother and sister who stood beside you

At attention in the desert summer sun

With sweat dripping down their faces

Unable to wipe it away

Because you are at attention, after all

As the flag-draped coffin is loaded

Into a plane bound for home.

And after the ceremony ends

And you return to the mission at hand

Someone will make a joke

Because that is how you all cope

But nothing is really funny

And everything is really funny.

You are in a world between worlds

While you are there it doesn't feel real

But when you get home, it feels faker still.

And you sit on your porch with nothing but memories

And your brothers and sisters are on their own porches

In their own silent homes

And you puzzle about what you had seen

About the enemy who was also a father, a brother, a lover.

This truth clashes with what you've been told.

This truth doesn't fit next to the shape of that coffin.

You have a tan on your face from that desert sun

And people will ask you if you had any fun

And the truth is, you did, but you can't explain to anyone

That there is pride.

There is also some guilt.

Because how can you enjoy war, even a little bit?

There was that coffin after all.

It passed so close to you

You could have brushed it with your fingertips.

Transition and Veteran Resources

Career and civilian transition guidance, geared towards helping servicemembers plan their careers and help transitioning servicemembers succeed in civilian life.

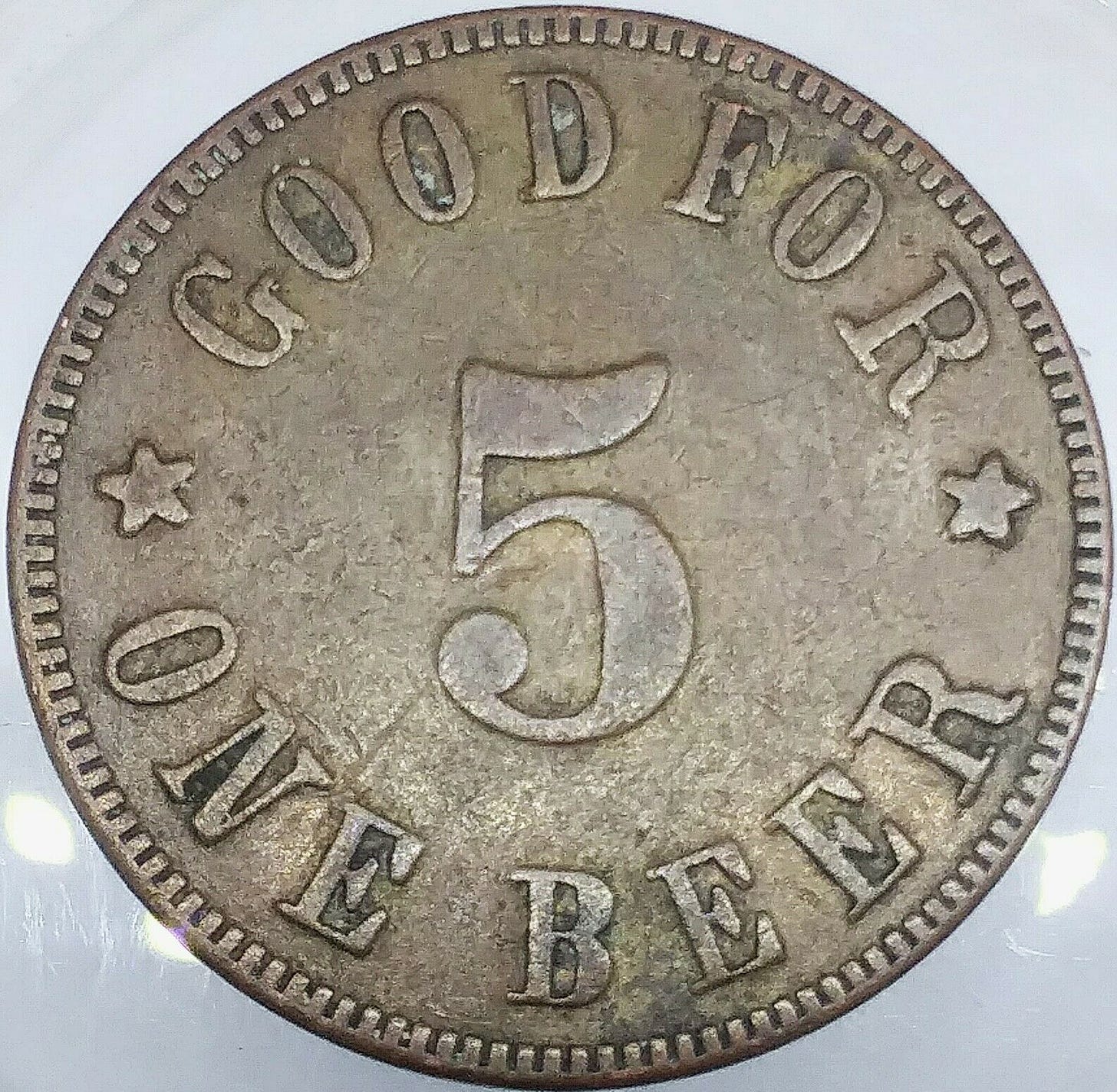

Object 9: National Home Beer Token - Michael Visconage, Chief Historian, Department of Veterans Affairs

Beer token, Central Branch-NHDVS, Dayton, Ohio. (Private collection)

“The beer hall is more attractive to a large number of the members than either the library or reading room.” – Edward Cobb, Civil War Veteran and resident, Southern Branch-National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers

Beer halls and beer gardens were familiar to Civil War Veterans who resided at branches of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (NHDVS). A predecessor to the modern VA medical campuses, the NHDVS system was established for Union Veterans after the war. The military-like setting included barracks-style housing, uniforms, formations, and a disciplinary system to maintain order. Veterans had assigned duties such as raising crops, tending the small herds of domesticated animals, and performing kitchen labor. Residents also formed marching bands and baseball teams, cultivated flower gardens, and engaged in a variety of other leisure and recreational activities. Many sites also established on-campus beer halls.

Alcohol consumption was commonplace among Civil War soldiers—and Veterans. This led to habitual intemperance among Veterans and incidents of drunkenness. NHDVS managers attempted to prevent residents from overindulging through rules limiting alcohol on campuses. Regulations also discouraged residents from frequenting establishments outside NHDVS gates willing to sell them as much liquor as they could consume. The creation of on-campus beer halls was an agreeable compromise for controlled access to alcoholic beverages.

Residents drinking beer in the Recreation Hall (known as the "dugout") in the Western Branch-NHDVS, Leavenworth, Kansas, sometime between 1898 and 1907. (VA photo)

The Northwestern Branch-NHDVS in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, began selling beer on the grounds in the late 1870s. In 1887 the Central Branch in Dayton, Ohio, reported reduced rates of drunkenness and improved order after opening a beer hall. NHDVS administrators limited consumption in these beer halls by selling beer tokens or tickets that were exchanged for beer. The compromise was welcomed by administrators and Veterans alike.

Tokens were round and made of brass or other metals, usually less than one inch in diameter. They were produced for NHDVS sites by craftsmen like James Murdock, Jr., an engraver from Cincinnati, Ohio.

At the Southern Branch-NHDVS in Hampton, Virginia, resident Edward Cobb recalled, “The quality of beer is of the best, and the glasses are large. On pension day and for a week afterward, the place is crowded; the men [are] standing in long lines.”

In early 1907, as the prohibition movement gained momentum nationwide, Congress banned alcohol at National Homes, and the era of the beer halls came to an end. By this time, the number of Civil War Veterans was declining. After World War I, a new model of veteran care replaced the self-sustaining National Home campuses.

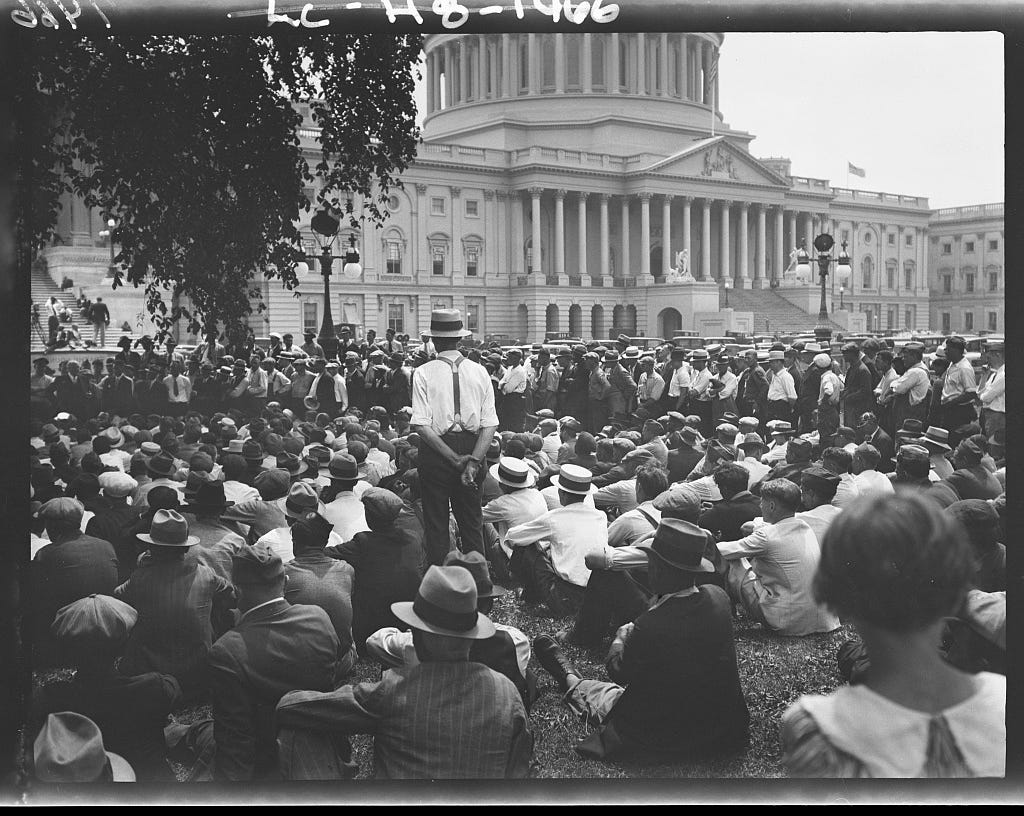

Object 21: Bonus Army - Alexandra Boelhouwer, Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, Veterans Benefits Administration

Bonus Army Veterans on the grounds of the U.S. Capitol, in the summer of 1932. (Library of Congress)

After World War I, Americans discharged from military service faced a difficult homecoming. Many struggled to find work in the tight labor market created by a post-war recession. They also felt ill-used. During the war, civilian workers benefited from a booming economy and enjoyed wages that far exceeded their own military pay. In the early 1920s, Veterans took their grievances to Congress. The newly formed American Legion and the more established Veterans of Foreign Wars led the way in lobbying for a one-time cash payment that would compensate Veterans for their missed earnings. In 1924, Congress passed the World War Adjusted Compensation Act, which awarded Veterans interest-bearing certificates with a face value of up to $625. But the law came with an important proviso: the certificates could not be redeemed until 1945.

Even with its deferred payout, the Bonus Act, as the bill was called, satisfied Veterans’ demands for some form of monetary compensation for their service. Their attitudes changed, however, with the onset of the Great Depression. The economic crash sent unemployment rates soaring and caused immense hardship for millions of Americans. Veterans were particularly hard hit by the crisis and they appealed to the government for immediate payment of their bonus certificates to alleviate their financial distress. When the administration of President Herbert Hoover proved recalcitrant, they mobilized for action.

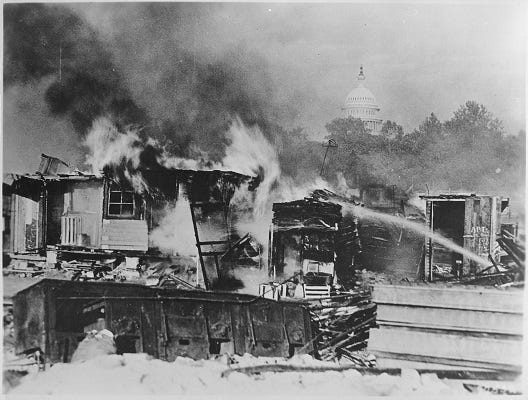

Bonus Army camps went up in flames after the U.S. Army evicted protesters on the night of July 28, 1932. The dome of the Capitol Building is visible in the distance. (National Archives)

In the summer of 1932, an estimated 20,000 Veterans, many with their families in tow, descended on Washington from all parts of the country to petition Congress for their money. Dubbed the “Bonus Army” or “Bonus Marchers,” they settled in tents, cardboard shanties and wooden shacks in parks and empty buildings in downtown Washington. They also established their main encampment across the Anacostia River on a muddy expanse of land called the Flats. Their daily presence on the steps and grounds of the U.S. Capitol, however, failed to win over Hoover or enough members of Congress. After the Senate on June 17 rejected a bill authorizing payment of the bonuses, many of the marchers went home. But even after Congress adjourned for the season in July, several thousand stayed on to continue their protests at the Capitol building.

Fearful that the demonstrations would turn violent, Hoover and the District of Columbia Commissioners on July 28 ordered the police to remove the marchers from their downtown camps. Following a skirmish that left two marchers dead and three policemen injured, Hoover made the fateful decision to send in the Army to restore order. Later in the day, six hundred soldiers, some mounted on horseback, and six light tanks under the command of General Douglas MacArthur moved against the Veterans. The troops on foot threw tear gas grenades and the makeshift shantytowns on both sides of the river went up in flames. The Bonus Marchers dispersed and by July 30 the city had been cleared of their presence.