Letter from the Editor

A lifetime ago, I stood on the porch of a house in western Iraq. My job in those days was to be the eye of a storm I brought with me everywhere I went, and the sounds of screaming women and the crash of flashbang grenades inside made calm communication difficult. So, I went outside. Now, as the suburban dad of a teenager, I still do. But as explosive as parenting can be, there is generally no threat of actual rocket fire from within my perimeter.

Such was not the case that night in Iraq.

As I stood under the uncertain flicker of a porch light that had somehow survived an explosive door breach, a loud pop in the street, followed by the explosion of a rocket-propelled grenade, got my attention. Orchestrating chaos was my normal condition in those days, but this was an unwelcome addition. I thumbed the push-to-talk button on my radio.

“Dagger 80, did we just take RPG fire?”

One of the cordon gun truck gunners immediately broke in, “A guy just stepped out of an alley and shot an RPG at Vehicle 2. He’s gone now, and he was between us, so I couldn’t shoot him without hitting our guys.” I had arrayed vehicles at four corners around the target building because I’d envisioned the threat coming from outside. I had always done it that way. It was my method. It was the right method. My gun trucks had 7.62 and .50 caliber machineguns with which to repel external threats. But the threat had come from within the perimeter.

Two days later, briefing my platoon on activities planned for that night, I showed a graphic depicting our vehicles arrayed just as they had been before. Most of our vehicles were shielded from one another’s fire by houses, but two were in view of one another. Thinking of the geometry of fires, one of my Marines, a Sergeant, raised his hand.

“Hey Sir, what if we didn’t have a vehicle on one corner and we just locked it down by intersecting fire? Then we wouldn’t have a friendly fire problem like we did the other night.”

He was right. The way I had laid out the cordon, the way I had done it for months, was no longer effective. Another person, a junior to me, had a better way, leaving me standing before my subordinates, nakedly wrong, requiring me to compromise my self-image as the font of tactical wisdom for the good of the unit. That was a small price to pay in a life-or-death situation, so I acknowledged him, made the change, and thanked the Marine for having our collective back.

Compromise is a hell of a thing. It requires the humility to acknowledge there might be valid opinions outside of your own; that some of the needs of the whole might be more important than some of mine.

Assuming it continues, by the time you read this, the federal government will have been shut down for 31 days. If it continues until November 5, it will be the longest government shutdown in US history. Maybe it will be resolved by then. But it won’t render the point any less important: American politics, an endeavor expressly built for the purpose of compromise, has somehow become a take-no-prisoners street fight, and, from my perspective as just another citizen, the people we hired to orchestrate the chaos are unwilling to accept that someone else might have a better way to set the cordon.

I will not endorse one side or another, much less apportion blame. I have my own opinions, of course, but to me, it’s pointless to fight about who created the problem until it’s solved. But solutions often require compromise, and I don’t see many of our “leaders” recognizing that the way they’ve arrayed the vehicles actually contributes to the problem rather than the solution. Unfortunately, according to the Pew Research Center, the percentage of members of the two major parties who view one another in a “very unfavorable” light has increased by an average of 39% since 1994, coincidentally the year I became a second lieutenant.

It wasn’t always this way. According to Facing History and Ourselves, in 1960, fifteen years after the largest military mobilization in American history saw twelve million Americans mobilized in her defense, and that of the world, only 4% of both Democrats and Republicans said they would be displeased if their son or daughter married someone of the opposite party. I have to believe there is a lasting commonality and understanding built when 9% of the nation goes forward to fight an existential threat. Contrast that with 2019, the eighteenth year of the still sputtering Global War on Terror ™ ©, in which less than 1% of the “Thank YOU for YOUR service” generation chose to serve. By then, 45% of Democrats and 35% of Republicans assessed the suitability of their child’s potential spouse by their political affiliation. I suspect it’s worse in 2025, when the veterans who do serve tend to be partisans who align their loyalty as much to their brand as their constituency and nation.

I don’t know the answer. But I know I am a gun-toting tree hugger whose liberal wife was an ACLU lawyer and whose conservative best friend/best man/godfather to my child (and for whom I fill all those roles in return) is a Marine turned investment banker who hung a picture of Ronald Reagan in our college apartment. I know that I have friends who vote across the political spectrum, and I find goodness in all of them, or I wouldn’t be friends with them. I know I had a Manhattan liberal and a “Don’t Mess With Texas” conservative in that platoon the night we got attacked from within, and have no doubt either would have moved heaven and earth to come to the aid of the other. It’s the Dichotomy of the Barracks, imbued in all of us by shared adversity, and we allow the rest of the nation to reject it to our collective peril.

Part of protecting what shred of unity we still have is these monthly missives to you, the readers of Lethal Minds Journal. I beg you to get involved, be a voice for the issues in which you believe, but listen to others who might be an opposing voice. Find some common ground. For me, it’s in the woods or on the water, a place calm enough to hear one another. But maybe for you it’s right here in excellent professional work like Joe Aiello’s Are We Truly Decentralized? Maybe you need to hear what Katie Strain has to say about suicide. Perhaps it’s poetry from people who’ve been where you are, all the way back to coming home from Vietnam. Whatever you’re thinking about, we exist to amplify your voice. Make it heard.

Fire for Effect,

Russell Worth Parker

Editor in Chief - Lethal Minds Journal

Submissions are open at lethalmindsjournal.submissions@gmail.com.

Dedicated to those who serve, those who have served, and those who paid the final price for their country.

Lethal Minds is a military veteran and service member magazine, dedicated to publishing work from the military and veteran communities.

Two Grunts Inc. is proud to sponsor Lethal Minds Journal and all of their publications and endeavors. Like our name says we share a similar background to the people behind the Lethal Minds Journal, and to the many, many contributors. Just as possessing the requisite knowledge is crucial for success, equipping oneself with the appropriate tools is equally imperative. At Two Grunts Inc., we are committed to providing the necessary tools to excel in any situation that may arise. Our motto, “Purpose-Built Work Guns. Rifles made to last,” reflects our dedication to quality and longevity. With meticulous attention to manufacturing and stringent quality control measures, we ensure that each part upholds our standards from inception to the final rifle assembly. Whether you seek something for occasional training or professional deployment, our rifles cater to individuals serious about their equipment. We’re committed to supporting The Lethal Minds Journal and its readers, so if you’re interested in purchasing one of our products let us know you’re a LMJ reader and we’ll get you squared away. Stay informed. Stay deadly. -Matt Patruno USMC, 0311 (OIF) twogruntsinc.com support@twogruntsinc.com

In This Issue

Across the Force

Are We Truly Decentralized? A Reflection on Command Philosophy in the Modern Marine Corps

The Written Word

Silent Issued Item

What is Moral Injury

Opinion

Who Wants to Buy the First Round?

Poetry and Art

Storms of summer

Oak Knoll Stop Off

The wind and waves

Bagram

Health and Fitness

Debunking Physical Fitness Myths for Female Service Members

Across the Force

Written work on the profession of arms. Lessons learned, conversations on doctrine, and mission analysis from all ranks.

Are We Truly Decentralized? A Reflection on Command Philosophy in the Modern Marine Corps

Joe Aiello

While the nature of war is enduring, the character of warfare is shifting. As the Marine Corps continues to adapt under Force Design 2030, it is essential that we reflect on how our doctrine is written—and how it is applied—to ensure we are prepared for the future fight. One area that warrants this reflection is our philosophy of command. Doctrine shapes culture, and culture drives action. How we define “command” and “control” will determine how effectively we can fight in distributed, complex environments.

Before starting that discussion, it is useful to lay out several key definitions from the Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (June 2025):

Command: The authority that a commander in the armed forces lawfully exercises over subordinates by virtue of rank or assignment. (JP 1, Vol. 2)

Control: Authority that may be less than full command exercised by a commander over part of the activities of subordinate or other organizations. (JP 1, Vol. 2)

The Marine Corps’ philosophy of command is founded on decentralized command and decentralized control, implemented through the use of mission tactics. MCDP 1, Warfighting (p. 4-9) states:

“The principal means by which we implement decentralized command and control is through the use of mission tactics, which we will discuss in detail later.”

Mission tactics are then defined as:

“The tactics of assigning a subordinate a mission without specifying how the mission must be accomplished. We leave the manner of accomplishing the mission to the subordinate, thereby allowing the freedom—and establishing the duty—for the subordinate to take whatever steps deemed necessary based on the situation.” (MCDP 1, pp. 4-18)

This philosophy has long been a hallmark of Marine Corps maneuver warfare. It emphasizes initiative, trust, and disciplined independence at every level. However, it also raises an important question: Is our command truly decentralized, or simply delegated?

The first echelon of command in the Marine Corps is typically a Lieutenant Colonel (O-5) commanding a battalion or squadron. Below that level, leaders exercise authority by virtue of delegated command or operational control. If “command” is only held by the commander of a battalion and above, then by definition, orders issued to company or platoon leaders are acts of control, not command.

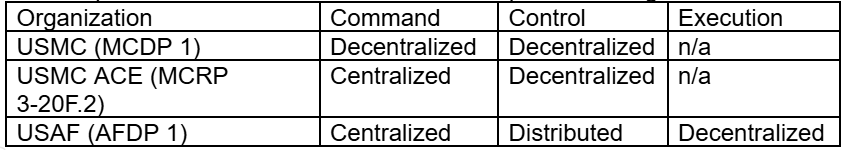

This distinction matters. If mission tactics occur within a structure where command remains centralized but control is delegated, then our practice may align more closely with the Air Force or Aviation Combat Element (ACE) philosophy than with the pure decentralization described in MCDP 1. The difference is not merely semantic—it affects how we empower leaders and how we design systems to support them.

The Aviation Combat Element and Centralized Command

Marine aviation, by necessity, operates under a different philosophy of command. As outlined in MCRP 3-20F.2, Marine Tactical Air Command Center Handbook (pp. 1-7):

“The Marine TACC uses centralized command to establish priorities and ensure unity of effort of MAGTF air operations. The ACE’s aviation assets are finite, and the air groups and squadrons will likely be located at several bases. Centralized planning and direction are essential for coordinating the efforts of all the ACE’s assets.”

This statement represents a deliberate departure from the “decentralized command” model of MCDP 1. The ACE relies on centralized command to allocate scarce air assets effectively and maintain unity of effort across vast distances and multiple mission types. Yet, once those missions are assigned, control and execution are decentralized to subordinate agencies like the Direct Air Support Center (DASC) and Tactical Air Operations Center (TAOC), mirroring the broader maneuver warfare principles of initiative and flexibility.

The key takeaway is that even within the Marine Corps, different elements apply different command philosophies based on their operational context and technical requirements.

The U.S. Air Force codifies its approach in Air Force Doctrine Publication 1 (AFDP 1), describing its philosophy as centralized command, distributed control, and decentralized execution:

“Centralized command is the organizing standard for the effective and efficient means of employing airpower; it enables the principle of mass while maintaining the principle of economy of force. Because of airpower’s potential to directly affect the strategic and operational levels of warfare, it should be commanded by a single Airman, the air component commander. Distributed control exploits airpower’s flexibility and versatility to ensure that it remains responsive, survivable, and sustainable. Decentralized execution is the delegation of authority to achieve effective span of control, foster disciplined initiative, and empower subordinates to exploit fleeting opportunities.” (AFDP 1, p. 13)

Interestingly, this framework parallels much of the Marine Corps’ language in MCDP 1. The Air Force emphasizes initiative and subordinate freedom within commander’s intent—just as Marines do—but explicitly recognizes the need for centralized command at the operational level to ensure unity of effort for assets with strategic effect. In this sense, the Air Force’s philosophy is functionally identical to the Marine ACE’s: centralized command, decentralized execution.

If we step back and look across the services, a pattern emerges:

Viewed together, these philosophies suggest that the Marine Corps—especially when integrating air, ground, and cyber effects—is already operating from a hybrid model that resembles centralized command, distributed control, and decentralized execution. Mission tactics thrive within this model because they depend not on the absence of command, but on trust, clarity of intent, and disciplined initiative within a unified framework.

Why discuss this at all? Because the character of war is changing, and with it, the implications of command and control. As Force Design 2030 matures, we are pushing increasingly lethal and networked capabilities—such as unmanned systems, loitering munitions, and precision fires—down to the lowest tactical levels. These assets, once the purview of higher headquarters, now have the potential to create operational and even strategic effects.

If company-level or platoon-level units can employ capabilities with such reach, the Corps must clarify who commands, who controls, and how unity of effort is maintained across distributed operations. The ACE’s rationale for centralized command—unity of effort, coordination of finite assets, and synchronized priorities—may soon apply to ground-based unmanned or long-range fires units as well.

This is not an argument to take initiative away from small-unit leaders. On the contrary, it is a call to reexamine how we define and apply “decentralized command” in a force that is increasingly capable of influencing the battlespace far beyond its traditional boundaries.

The Marine Corps prides itself on decentralized command and the empowerment of subordinates through mission tactics. Yet our doctrine, when compared with that of Marine aviation and the U.S. Air Force, suggests we may already operate under a more centralized command model than we care to admit. As we move deeper into an era of distributed maritime operations and unmanned warfare, it is worth asking: are we doctrinally honest about how we command, control, and execute?

Reflecting on this question is not a challenge to Marine Corps tradition—it is an affirmation of it. The essence of maneuver warfare is adaptability. Our philosophy of command should be no different.

References:

Department of the Navy, Headquarters United States Marine Corps. (1997). Warfighting (MCDP 1, PCN 142 000006 00). U.S. Government Printing Office.

Department of the Navy, Headquarters United States Marine Corps. (2018). Marine tactical air command center handbook (MCRP 3-20F.2; formerly MCWP 3-25.4, PCN 144 000252 00). U.S. Government Printing Office.

Department of the Air Force. (n.d.). Air Force doctrine publication 1: The Air Force. U.S. Government Printing Office.

The Written Word

Fiction and Nonfiction written by servicemen and veterans.

Silent Issued Item

Katie Strain

I am convinced that we were issued the burden of suicide when we joined the military.

The first time a Soldier came to my office crying, unable to talk between the tears, I was introduced to this issued item. It scared me. I had trained to handle that exact situation in AIT and knew what to say and the steps to take, but I wasn’t acquainted with its darkness yet. My boss, the unit chaplain, was somewhere else, and I had to keep the Soldier calm until he picked up my call.

“I don’t think I can do this anymore…”

I remember her words as she gripped my leg from the chair across from me.

“I can’t live anymore.”

The next was a few months later, a male Soldier this time. He was of a higher rank than I, an NCO. But the same sentiment was there. He couldn’t do it anymore. That is the feeling that suicidal ideation or even being suicidal will bring to a person. Active suicidal ideation is when a person has persistent thoughts about ending their life, accompanied by a clear plan to do so, whereas suicidal ideation in a general sense refers to having thoughts of ending ones life but without a plan to do so. It may not be objectively rational for those looking at it, but it seems objectively rational for the one experiencing it. And that feeling is virtually everywhere.

Working as a unit chaplain assistant meant I dealt with mental health issues in all sorts of locations. Usually outside of my office, meeting Soldiers and officers where they worked. Motor pool days were big for unloading stress. Looking back at it now, I see that it was not only a pervasive issue but a “systemic” one. And frankly, I hate that word, or any overused buzzword, really. But in this case, it’s true.

The military issues us a silent item.

It doesn’t fit well in a rucksack, or in a duffel bag. It’s not really an item you can wear, either. I used to have long talks with my chaplain later on, towards the end of my career, about the way we had to handle it in the Army. Units liked to send Soldiers and NCOs to us when they saw someone suicidal, not understanding that we were not mandatory reporters but had to keep it confidential. It could be so challenging and almost a barrier if you weren’t creative. But often, the unit leadership was already aware and just wanted us involved.

For instance, one early Saturday morning when I was a staff sergeant in Germany, I received a frantic call from the barracks on our little base.

“Sergeant, we need you here. He said he wants to die!”

No matter what I could or couldn’t do, I would always respond to a Soldier who was expressing suicidal ideation or had actually acted upon it. I rushed to the barracks, driving through my tiny village that looked like a Norman Rockwell painting, thinking over this epidemic of our thoughts and mental states. The E5 I was rushing to see was always good to go, always at work on time, and always taking care of his Soldiers. What was going wrong?

The answer was more than subtle, more than nuanced. Even now, I see it as an overall problem that can’t be eradicated with various mandatory training sessions or even simply sending service members to mental health. It is issued to us when we join. We will all experience it, if only from those around us. But there is a way to view it and then handle it. Of all the hundreds of mental health counseling sessions I conducted, whether formally or informally, a few things were constant.

People find pain in relationships and with finances.

This isn’t universal to the military. It’s very much a part of civilian life, too, but it is exacerbated by the military. Living in states and countries far from where you have roots and family is hard. Having to work with such different types of personalities in a very strict environment is hard. Juggling physical fitness and long work hours is hard. The military is one of the roughest places to work on all fronts.

It’s no wonder that suicidal ideation becomes so common.

Once you leave the military, this problem then becomes an epidemic. Veterans die by suicide more than servicemembers on active duty. Like it or not, we get to bring home our issued item; it doesn’t get turned into CIF with all the rest of our issued gear.

So what do we do?

How can we stop suicides from being so high?

We have to view it through the lens of resiliency.

Often, when I have online conversations or text conversations with fellow veterans in distress, they need someone to listen to them first. Listen. Not to give advice or tell them what I would do, but try to save them. Just listen. Once they have laid out what is going on in their lives, I can remark on how resilient they actually are – to endure such crap and hardship all the while continuing to live.

This shift in focus is literally a game-changer.

Will it stop everyone from continuing to have suicidal ideations? No. I should know. I still experience this myself from time to time. I suffer from pretty debilitating PTSD and TBI from my time in Iraq. I have found that often redirecting focus to how damn resilient you are does work, but if it’s not enough, further counseling and treatment is one hundred percent recommended and needed.

Resiliency also demands that we find coping strategies. That is what we were taught to do in the military: cope and adapt to the stress, so we can continue to drive on and keep showing up every day. In Iraq, for instance, that is an ability we all developed pretty early on. Route clearance will suck the soul out of you. I experienced it and saw it happening to the guys firsthand. We became invincible in our ability to stay on track and keep “doing.” There was no other choice.

So let’s ask: can the issued item be harnessed for good? Or is it doomed to be a burden none of us want and that we must carry forever?

Military members have the unique opportunity to show the rest of the world what it means to endure hard things. We can show society that, despite the madness of people quitting on you, cheating you, and harming you, you can still figure out a way through. Money comes and goes, but this mindset – that suicidal thoughts do not have to be the way to handle money problems or any other kind of problem, and that if suicidal thoughts crop up, they can be dealt with respectfully – is simply golden.

The silent issued item is widely considered taboo. So you might balk at my audacity to call it out, to speak so freely about it. But I think we shouldn’t hide what has become the number one killer of our population. It deserves to be brought out of the duffle bag and the rucksack and examined. In the end, the chaplain and I concluded that it will probably always exist in society, especially in the military. But there is one last secret that we often fail to recognize when it comes to suicide and suicidal ideation.

It doesn’t have to hold the power it tries to grasp for and steal from us.

We can tell it to pound sand!

Be there for your fellow veteran, helping them see their problems for what they are (and what they are not); help them see that there are solutions for what drives the issued item to take over. This is what we need to keep doing. Empower each other to rely once more on our resiliency so our community doesn’t have to lose another valuable member. When we do this, it can help protect us from suicide and weaken the damaging, contagious effect suicide has on others.

The military issued us a silent item, but that item is defective as hell, and it’s time we all talked about it. Start the conversation.

Our lives depend on it.

What is a Moral Injury?

Heather O’Brien

A moral injury: The damage done to one’s conscience or moral compass when that person perpetrates, witnesses, or fails to prevent acts that transgress one’s own moral beliefs, values, or ethical codes of conduct.

This is a relatively new term in therapeutic circles. It has a nice sound too – as if the image it conveys isn’t really horrific. Not even the therapists with their neat clinical phrases have found a way to fully heal moral injuries. It’s considered something one must live with forever.

So what is a moral injury?

It’s the outrage of seeing a single man being beaten by a mob, and there is nothing you can do to stop it.

Day after day, it continues until you’re finally so numb you take bets on how long each beating lasts.

It’s the horror of hearing men “welcomed” to prison.

Or maybe it’s getting so accustomed to it that you laugh about it.

It’s no longer being worried about violent riots and hard pushes but enjoying them because you no longer need to exercise restraint – you can finally vent all the stress you’ve built up. The adrenaline rush of causing someone pain becomes an intoxicating drug.

It’s seeing a monster holding a gun reflected in someone’s eyes and realizing the monster is you.

It’s coming back to the land of normal people, loving and hating them because they seem naïve and happy. Knowing it’s good that they are happy and hating them because you can’t be anymore.

It’s hearing/seeing every terrible thing you couldn’t stop every time someone calls you a hero. What hero just allows injustice day after day? No hero sits by and laughs at another’s agony.

Pretty words and nice scientific phrases cannot accurately describe it. A moral injury is a ripping of the heart, a shredding of the soul, and a broken spirit. It whispers the only way to silence the agony is to be silenced. This injury points the wounded in only one direction: death.

Thankfully, I know a Physician who takes delight in healing not only body wounds but mental, spiritual, and soul ones as well.

So when a child’s happy scream conjures up images of brutality, I don’t have to stay in that terrifying memory. My God heals physical and mental wounds.

When a well-meant word about my service makes me cringe as I remember every dishonorable thing, I remind myself that my God is my Redeemer.

Against all psychological reasoning, my wound is healing.

The injuries inflicted by the atrocities of being unable to help others in need and letting myself fall into evil are being eradicated.

The poison is being sucked out.

This moral injury is one that will not control my life any longer.

Opinion

Op-Eds and general thought pieces meant to spark conversation and introspection.

Who Wants to Buy the First Round?

Benjamin Van Horrick

As the Marine Corps approaches its 250th birthday, it faces a choice: throw a party or reckon with its future. Force Design overhauled the Corps, divesting capabilities like tanks to invest in platforms like drones and anti-ship missiles, betting on a future Pacific war. Critics call it reckless. Supporters call it visionary. But with the Davidson Window, the time when the PRC is most likely to initiate military action, approaching, there’s no time left for polite disagreement. Secretary Hegseth demanded frank talk from flag officers. The Corps should demand the same of itself. Topics should include whether divested tank battalions were worth the trade, what Ukraine teaches about drone warfare, and whether distributed operations can survive modern surveillance. Before we cut the birthday cake, we need to examine Force Design’s assumptions and whether the Corps can still win in any clime and place.

Force Design’s advocates and detractors continue waging a fierce debate online. The opposing factions publish tomes but rarely, if ever, meet face-to-face. This debate resembles faculty lounge arguments, unbefitting warriors on the front lines. Debate does not mean discord. The discourse signals the Corps’ health, not its rot. Articles and online essays refine ideas and challenge assumptions. However, the debate remains online and detached from those charged with implementing Force Design — enlisted Marines. An open debate would resemble the long-form podcasts popular with young men—who make up most of the Marine Corps. Debating Force Design face-to-face will sharpen ideas, drive innovation, and build ownership. Force Design and the Stand-in Force concept remain unfinished products. Like any operations order, bottom-up refinement fills gaps and pushes ownership to the lowest levels.

So where should this debate happen? A bar should hold this convocation, not an auditorium, a fitting venue considering the Corps was founded in a tavern. The proceedings should be filmed and livestreamed across the globe to foster transparency and discussion. So much of the debate originates from the Beltway, but the stakes are highest in the First Island Chain. Junior Marines now crave the long-form discussion they consume daily. The impending National Defense Strategy makes a Corps-wide convocation urgent. The Marine Corps reached its yearly reenlistment goals in two weeks—proof of a mature, committed force. This force deserves mission clarity. A convocation serves as an azimuth check, not a course correction. Secretary Hegseth didn’t just permit frankness—he demanded it.

For a service that’s “First to Fight,” the Corps should lead through disciplined, intellectual debate. Force Design has provoked passionate investment from both sides, proof of how much the Corps means to those who earned the Eagle, Globe, and Anchor. Frank, substantive discussion – not petty sniping – is needed now more than ever.

Who wants to buy the first round?

Poetry and Art

Poetry and art from the warfighting community.

Storms of Summer R.H. Booker Thunder rolls as cows look towards the distant black, then at me, sitting beneath the mesquites, much of the rain beyond us. Nothing like lightning within a stone’s throw to remind you of mortality. Eternity not all so far away. Death doesn’t strike fear in me, instead a homesickness for rivers and streams, valleys and oceans, though there is much better to follow. There are no atheists in foxholes– so why not face it now? Prepare yourself to walk above through forests of pine, the songs of Heaven’s birds far too much for us here on earth. Oak Knoll Stop Off K.R. Harbert Back to the world, fresh from Nam— new orders: TDY to Oakland. “We promise less than six weeks. Honest.” Back in dress whites, headed for Oak Knoll— Naval Hospital Oakland, built in ’42: eighteen floors, forty wooden clinics linked by ramps— for all the chairs. Five hundred beds. Seven hundred to a thousand patients each month. Assigned to Thoracic Surgery— Alfa and Bravo: fifty beds total. Alfa: twenty-five chest wounds from Nam. Bravo: twenty-five with cancer. Corpsmen and nurses ran the shifts. Welcome home. We give you pain to make you better— the oxymoron of healing. Business was good. Never empty, day or night. Chinooks dropped off the Nam patients— faster than any ambulance. Cancer patients came by car. Familiar sounds— day and night. Did I really come back to the world? On Alfa side, I held retractors, suctioned wounds, changed dressings. They made me feel at home— I knew where they’d been, what they’d done, what they’d survived— and who didn’t. On Bravo side, life slowed down— older Marines and sailors coughing through the night, thirty-year-olds who looked eighty, living day to day, fearing sleep. We carved hope from lungs. They asked me to hold cigarettes to their trachs when they went out for “fresh” air. Dealers brought free cartons— Luckies, Camels, Marlboros galore. Funny—Alfa side couldn’t smoke. At night, I’d sneak grunts out the windows to see their girls, then back in again— dressings changed, wounds suctioned, sutures done, ready for 0700 rounds. Weeks blurred into months. “Just one more extension,” they said. Six months later—orders. Time to go. I quit smoking. I’d watched the grunts walk out alive, and the cancer patients carried out in bags. Fifty years later, Agent Orange introduced me to the big C. So it goes Time repeats itself, daily. The wind and waves E.B. How easily I forget The shape of me Each edge diminishes By your presence And I become Entirely immersed Part of the molecular Rave of being present In the room with you Bagram Isaiah Garrod

Health and Fitness

Guidance for improving physical and mental performance, nutrition, and sleep.

Debunking Physical Fitness Myths for Female Service Members

Alissa Newman, PhD, CSCS; Tristan Irwin, US Army Veteran, and LtCol Tara Sutcliffe, USMC

Navigating fitness as a military woman can feel like a crapshoot. Advice is everywhere — but much of it is misleading, contradictory, or just plain wrong. One source says eat more, another says eat less. Train harder. No, rest more. Take this supplement. Wear that gear. So, who’s right?

The good news: after decades of neglect, the body of scientific evidence on how to train female tactical athletes is finally catching up. In the last few years, there has been a surge in research on women’s physical performance. As new studies emerge, we’re better equipped to challenge the myths surrounding women’s fitness in the military. While the science isn’t yet as deep as it should be, it’s growing fast. Researchers are finding that while sex-based differences matter, most fundamental training principles still apply. Women aren’t small men, but they’re not a different species either.

This article will arm you with the latest science on effective training for female tactical athletes. Whether you train, coach, or are a military woman yourself, you’ll find practical insights for cutting through misinformation. We’ll start with an overview of basic anatomy and physiology, explore how they shape performance, and tackle the most persistent myths in the field.

Key Concepts Explained

Let’s start by defining a few important terms. First, we define a “female tactical athlete” as a woman in the military (or other physically taxing profession) whose occupation has significant physical fitness demands and the potential for exposure to life-threatening situations. In this piece, we use “female tactical athlete” (or FTA) and “military woman” interchangeably. Second, “anatomy” refers to body size and structure. This includes physical and structural characteristics like height, weight, limb length, and torso length. Finally, physiology refers to the inner workings of the body, such as hormones and metabolic responses.

Anatomically, women tend to possess less muscle mass and be smaller, lighter, and shorter than their male counterparts. Women also tend to have less upper body mass. Physiologically, women have female sex hormones such as estrogen and progesterone and have lower levels of testosterone compared to males. These sex hormones and their fluctuations across the menstrual cycle (MC) have been purported to impact substrate metabolism, based on cell and rodent studies. Among human women, these hormones have only a small effect and are likely to be overridden by factors such as nutrition, fitness level, and exercise duration and intensity.

There is minimal to no evidence suggesting that women and men respond differently to exercise. That’s good news; it means we already have a strong foundation for training FTAs without reinventing the wheel. That said, nuance exists. For instance, progesterone can raise core temperature, which has implications for women training in hot or humid environments.

Let’s get into some myths!

Myth 1: Women should be training using “women-specific movements.”

We’ll get right to it: “women-specific movements” don’t exist. A woman might need a variation of a given movement based on her size, shape, mobility, or fitness level, but not solely because she is female. Bodies come in all shapes and sizes, and everyone moves according to their own body structure and physical capacity. Just as a man and a woman might perform the same exercise differently, a tall woman and a short woman might perform differently as well. Someone with long limbs is going to look different doing a squat than someone with shorter limbs, regardless of sex. Everyone—not just women—must figure out how their own bodies perform a movement best. Movements are just movements; they don’t belong to one sex or the other.

Similarly, differences in metabolic response to exercise are largely dictated by individual fitness levels, not sex. Let’s say two people go out for a run. One of them comfortably runs two miles in 12:00 minutes. The other runs two miles in 17:30 minutes and describes it as “difficult.” If they run five miles together at an 8:00 minute-per-mile pace, one of them will experience the run as an easy jog, while the other will be performing high-intensity work. The same exercise can elicit varying metabolic responses, but these differences are due to their fitness levels, not biological sex. If Person A has a maximum deadlift of 250 pounds and trains alongside Person B whose maximum is 450 pounds, lifting the same weight will feel very different for each of them. For Person A, lifting 225 pounds represents 90% of their maximum, while for Person B it’s only 50%. As a result, the effort is highly demanding for Person A but more like a warm-up for Person B. This difference produces distinct metabolic responses not because Person A is a woman, but because lifting 90% of one’s maximum is a very different physiological stimulus than lifting 50%.

Myth 2: “Training like a man” is bad for you.

To date, there is no clear consensus on what “training like a man” means. Is it lifting heavy weights? Doing squats, bench presses, and deadlifts?

We’ve been sold a story as women that we should avoid “getting bulky” at all costs (a story that deserves to be sunk to the bottom of the ocean forever). This story links lifting heavy weights with becoming “too muscular,” equates “training like a man” with “looking like a man,” and ultimately scares women away from the barbell. It goes on to tell us we should “tone,” “sculpt,” and stay small. But here’s what that story gets wrong: “toning” and “sculpting” aren’t real physiological processes. If you want muscle definition, you have to build muscle and potentially reduce body fat. If you want strength, you need to train your nervous system to recruit muscle fibers more efficiently. And to do either, you have to lift heavy.

Quality programming is paramount for tactical athletes of any sex. Occasionally, “training like a man” is code for poor training, like mistaking a “smoke session” for a productive workout. While smoke sessions are deeply rooted in military culture, they should be used judiciously, not in a strength-building program. Injury risk rises in these cases, not because you are a woman, but because the program is flawed.

What everyone should do, regardless of sex, is train smartly. This means following a program that meets you where you are and progresses appropriately (shameless plug here for our nonprofit, The Valkyrie Project!). Focus on your specific weaknesses, rest when needed, and train with intention. Don’t confuse complicated with effective, or assume that a workout’s value is measured by how hard it feels. Fuel your body well; you may need more than you think to truly support your training, especially when balancing bodyweight standards with strength goals. You’ll likely be surprised not only by your progress but by how much better you feel day to day.

To perform at a high level as a FTA, you need to lift heavy weights and train hard—not “train like a man” or “train like a woman.” Just train smartly, incorporate progressive overload as adaptation occurs, commit to the process, be patient, and consider getting a coach if you feel like you need additional support.

Myth 3: You need to train in accordance with your menstrual cycle (MC).

The answer to this is “probably not,” but your mileage may vary!

Recent studies suggest that MC phase-based training (both resistance and aerobic) does not promote superior training adaptations compared to a more traditional training program. While research does suggest that performance may be trivially reduced during the early follicular phase of the MC, this finding is likely inconsequential outside of elite athletics.

While sex hormones themselves might not alter exercise performance, MC-based symptoms may have negative impacts. In one study, researchers found no correlation between sex hormone levels and exercise performance, but they did see a reduced performance associated with factors such as motivation, perception of performance, and pain.

If you find yourself dealing with severe MC symptoms, you may benefit from adjusting your training accordingly. Maybe you rearrange weekly training sessions so your rest days or easier days align with the more severe symptom days. Maybe this means reducing weight, repetitions, or sets to accommodate symptoms. If you can push through fatigue or lack of motivation safely, that’s an option too! It can be very valuable to remember that how you feel is not always indicative of how you will perform. Learning how to show up even when things aren’t great is a valuable skill set for military members.

Myth 4: Women need specific injury prevention exercises.

Maybe! Research suggests that low back pain and injuries to the hip, thigh, and lower leg are more frequent in female soldiers. However, many injuries sustained in the military can be classified as overuse injuries, which are often preventable with a smart training program (see Myth #2). When military women get injured, it’s likely not because they are performing specific exercises, but rather because their training program isn’t suitable.

In military settings, many of the injury differences between men and women likely stem more from variations in fitness levels than from sex itself. Like with metabolic response differences, the discrepancy in injury tends to disappear when controlling for fitness in both basic training and in the conventional force.

That said, incorporating exercises that build core/postural strength (like heavy carries) and address upper or lower body strength deficiencies can be valuable for reducing risk of injury, as can maintaining an adequate range of motion through mobility training. If you have a recurring injury or specific pain area, we recommend working with a knowledgeable physical therapist.

An important caveat is that this does not apply to women in the postpartum period. Women returning to duty postpartum need extra support and specific exercises to safely resume physical training.

Myth 5: You need to eat in accordance with your menstrual cycle.

Unlikely, with a few exceptions. And it doesn’t have to be complicated. (However, if you feel better doing this, keep doing whatever makes you feel good and perform at your best.)

There is some evidence that energy expenditure can increase by 8-16% during the luteal phase as compared to the follicular phase. During the luteal phase, estrogen may slow down the process of creating new glucose molecules and cause female athletes to be more reliant on fat for fuel during exercise. Together, this may make high-intensity exercise more difficult, as carbohydrate is the primary fuel for exercise at higher intensities. Consuming additional carbohydrates before, during, and/or after your workouts can help if you feel wiped out during your luteal phase.

Hungrier in the latter half of your menstrual cycle? Try eating more. Struggle with making progress in the gym? Try eating more. Struggle with recovery and feel sore all the time? Try eating more. Struggle with keeping energy up after a workout? Try eating more. If you are eating enough to support your activity levels, consider increasing carbohydrate intake to a larger share of your total intake.

As a general guideline, female athletes should aim to consume ~45 kcal per kg of fat-free body mass for optimal health and performance. For a 155-pound (70.5-kg) female at 25% body fat, this is roughly 2380 kcals per day. Optimizing macro- and micronutrients (based on MC or not) is ineffective unless you eat enough calories to support function. Working with a licensed sports/tactical dietitian can be helpful for nutritional support.

Training with Confidence

Navigating fitness as a military woman can feel overwhelming, but the truth is more straightforward than the noise suggests. While some sex-specific differences exist, the fundamentals of strength and conditioning apply to everyone. Training smart — progressing safely, fueling your body, maintaining mobility, and avoiding overtraining — remains the most reliable path to strength, endurance, and resilience. Research on female tactical athletes is finally catching up, providing evidence-based guidance to address sex-based nuances where they exist and cutting through myths and misinformation. While more research is needed, sticking to these core principles can enable military women to train with confidence, strength, and purpose.

The Valkyrie Project Inc., 501(c)(3), is a nonprofit that works in the realms of human performance, education, research, and advocacy to provide American female service members the tools they need for success across the full spectrum of military service.

——————————

This ends Volume 40, Edition 1, of the Lethal Minds Journal (01NOVEMBER2025)

The window is now open for Lethal Minds’ forty-first volume, releasing December 01, 2025.

All art and picture submissions are due as PDFs or JPEG files to our email by midnight on 20 November 2025.

All written submissions are due as 12 point font, double spaced, Word documents to our email by midnight on 20 November 2025.

lethalmindsjournal.submissions@gmail.com

Special thanks to the volunteers and team that made this journal possible.

Wonderfully stated

Excellent introduction. Well said.