Letter from the Editor

I’m going to be honest. I don’t know that I would have fallen into the category of the Secretary of War’s “fat generals” had someone been fool enough to elevate me to flag rank, but I fought the tyranny of the Marine Corps height-weight standard for decades, even as I spent most of my career in assignments in which “all it takes is all you got.” It was not an insubstantial issue in a service that generally shames and punishes fatness more than it encourages and rewards fitness (see: the Courthouse Bay MCX at Camp Lejeune, where it’s far easier to buy liquor, cigarettes, energy drinks, dip, and red dye #9 than an apple).

Fortunately, I’ve always had a desire to do hard things, a character trait only matched by my inadequately suppressed dislike of rules and my love of Waffle House. Accordingly, and as a bulwark against the Marine Corps Body Composition Program, I ran ultramarathons for decades, including three 100-mile finishes. It’s hard to be mad at a fat guy who runs 50 miles on Saturdays and beats you on the 3-mile PFT. But that was then, and this is now, when I am fifteen pounds past ten pounds past where I ought to be.

At 53, it just doesn’t come off as easily. That’s even more true when you seem to require some new surgery every six to twelve months for something you ignored for decades. But the instinct to do hard things is still there. So, a year ago, I hired a strength trainer and told him if I was going to be fat, I wanted to be strong. Specifically, I wanted to deadlift 405 pounds. I had no reason for that goal, but about nine months later, I hit it. Now I have surpassed that number, as well as exceeded my previous bench and squat records, which is awesome, and I am a day away from hernia surgery, which is not.

This brings me to my point.

There is a downside to virtually any meaningful endeavor (whatever that may mean for you), always someone ready with a criticism, or a knowing look, or an “I told you so,” smug in the confirmation that daring greatly is folly.

When I ran ultra-marathons, people who had never run out of sight seemed compelled to explain to me the dangers to my knees and other joints of “all that running.” When, after thirty-five years of it, I had foot surgery, it was confirmation for them that the preceding three and a half decades of my life had been folly. But they only saw the boot on my foot and the stupid tricycle scooter I pushed with one leg for six weeks. They were ignorant of the years I spent training, studying, talking to experts, and runners of greater experience than I to become better at something hard. They ignored the mental and physical growth that came from hours on my feet. They never watched a second day’s sunrise from a mountain ridgeline, knowing it was all downhill running from there.

When I started lifting heavier than at any point in the preceding 53 years, people who have never known the elemental joy of moving that which does not want to move explained to me the dangers to my back, my knees, and my shoulders. Again, they missed the coaching, the hours of practice, the repetitions of ever heavier weights that passed until the day the iron gave me its gift and moved precisely, if begrudgingly, as I desired. But they were right there when I got diagnosed with a hernia. “It’s all that weight!” they immediately diagnosed, ignoring the fact that my surgeon said the tear likely preceded my lifting (which admittedly had likely aggravated it).

It has all made me think of the days when I was a 160-pound Marine Lieutenant, jealous of those Marines and Sailors in my infantry battalion who underwent “The Indoctrination” required to gain acceptance into what was then Fifth Force Reconnaissance Company. I was too afraid of failure to attempt it. I just sat on the sidelines as they dared greatly, too busy perseverating on the downsides of possible failure to consider the possibility of success. But eventually I realized I would rather be someone who dares and fails than someone who sharpshoots other people’s willingness to do the same. That set me on the path I’ve followed, one that necessarily comes with aches and pains now.

“You’re going to regret all that running with a ruck when you’re older!”

I don’t. I’m glad I learned how not to quit in the face of discomfort.

“Your [insert body part here] is going to hurt someday!”

It does. I don’t give a rat’s ass.

“You’re going to hurt yourself lifting all that weight!”

Not really. It makes me stronger and prepares me for the next phase of life, when bone density will matter more than my VO2 max. And when something does tear, it’ll heal, or I’ll get it fixed, and I’ll train heavy again.

There are so many people living in fear of what might happen if they try, so many people who want to have done a thing far more than they want to do the things required to do it. Don’t be one. Life is short. There is no dishonor in giving your best effort and falling short. There will be something else for you, another place for you to excel, something I am discovering to great joy in my second act as a writer. Maybe your place is here at Lethal Minds Journal. We always need volunteer editors, writers, artists, and voice actors to keep this thing moving forward. This volume is damned near an all-Marine show; let’s write as we fight…jointly. Everyone in uniform with a good idea is welcome here.

Dare greatly! Email us at submissions.lethalmindsjournal@gmail.com

Fire for Effect,

Russell Worth Parker

Editor in Chief - Lethal Minds Journal

Dedicated to those who serve, those who have served, and those who paid the final price for their country.

Lethal Minds is a military veteran and service member magazine, dedicated to publishing work from the military and veteran communities.

Two Grunts Inc. is proud to sponsor Lethal Minds Journal and all of their publications and endeavors. Like our name says we share a similar background to the people behind the Lethal Minds Journal, and to the many, many contributors. Just as possessing the requisite knowledge is crucial for success, equipping oneself with the appropriate tools is equally imperative. At Two Grunts Inc., we are committed to providing the necessary tools to excel in any situation that may arise. Our motto, “Purpose-Built Work Guns. Rifles made to last,” reflects our dedication to quality and longevity. With meticulous attention to manufacturing and stringent quality control measures, we ensure that each part upholds our standards from inception to the final rifle assembly. Whether you seek something for occasional training or professional deployment, our rifles cater to individuals serious about their equipment. We’re committed to supporting The Lethal Minds Journal and its readers, so if you’re interested in purchasing one of our products let us know you’re a LMJ reader and we’ll get you squared away. Stay informed. Stay deadly. -Matt Patruno USMC, 0311 (OIF) twogruntsinc.com support@twogruntsinc.com

In This Issue

Across the Force

UxS Employment Across the MAGTF and the Warfighting Functions

Search and Destroy

The Written Word

Cycle of Violence

The Letter I Never Wrote

A River Runs Through Helmand

Poetry and Art

“A Warrior Untested”

Old Men and War

How to Write a Prose Poem, a Drill

Fit to Fight

The Beast of Burden

Health and Fitness

Chaos Training for the Tactical Athlete: Application Within Marine Corps A-IMC Detachment Hawaii

Across the Force

Written work on the profession of arms. Lessons learned, conversations on doctrine, and mission analysis from all ranks.

UxS Employment across the MAGTF and the warfighting functions

Tom Schueman

Enablers from unmanned system (UxS) battalions will impact every element of the Marine Corps’ MAGTF. UxS are modular and cross-functional by design; they are intended to be multi-domain assets. The use cases below show typical applications organized by warfighting function, while recognizing that UxS employment often blurs the lines between warfighting functions. Rather than attempt an exhaustive taxonomy of where each platform nests doctrinally, this essay offers conceptual UxS applications using current technologies. Survivability and lethality on the modern battlefield demand integration of these capabilities into the MAGTF at echelon, along with skilled and trained operators.

Maneuver:

Extend the reach of the infantry squad by proliferating High-Volume Multi-Mission Attritable Precision (HMAP) systems to the rifle squads — e.g., FPVs & Cerberus — a direct aerial fire-support platform equipped with a 40 mm grenade launcher

Extend the reach of the infantry battalion with loitering munitions — e.g., OPF, ROC-X, Altius, Switchblade, Spike, Rogue 1, and Hero

At echelon, equip squads, platoons, companies, and battalions with a mix of UxS to include UAS from nano to long-range/long-endurance; UGVs from throwbots and quadrupedals to large remotely controlled vehicles; and USV/UUVs from small swarming USVs to Autonomous Low-Profile Vessels (ALPV) that are over 65 feet long

Leverage Group 2/3 aircraft to be the hunters that provide persistent cross‑cueing with EO/IR, ground moving target indicator (GMTI), SIGINT, and laser designation

UGVs support route clearance, autonomy-enabled logistics with systems like AutoDrive (a fully integrated autonomous driving system), breaching, counter-mobility, and casualty evacuation - including attritable flanking scouts and first-person-view teams tied to battalion fires nets. Systems like THeMIS and Hunter WOLF provide commanders with reconnaissance and remotely operated weapons systems

USVs and UUVs extend the battalion’s reach across rivers, harbors, and contested littorals. They support littoral sensing, mining and counter-mining, maritime deception, and reconnaissance in support of sea denial and maritime domain awareness

Sustainment:

UGV platoons can move ammunition, water, and batteries forward; back‑haul casualties; and perform 24/7 perimeter patrolling.

The Company Gunny has a new tool. Platforms like Overland AI’s ULTRA vehicles can stitch the last tactical mile across broken terrain without risking convoys. Uncrewed logistics systems like ULS-A will give maneuver elements organic sustainment, reducing risk to convoys and keeping Marines supplied inside contested environments— e.g., Tactical Resupply Unmanned Aircraft System (TRUAS) and Medium Aerial Resupply Vehicle for Expeditionary Logistics (MARV-EL)

USV — e.g., the autonomous low-profile vessel (ALPV) enables logistics in contested environments, carrying 5 tons for 2,300 nautical miles

Information: Unmanned systems are sensors, but they are also messaging machines. Every feed is a potential truth captured, so that the reviewing commander can compete in an information environment where narratives are formed and promulgated over social media networks. Robotics sections aligned to MIGs connect tactical collection to operational campaigns. Electronic warfare payloads on Group 2/3 platforms execute distributed electronic attack under the MAGTF EW construct, complementing joint packages and enabling fifth‑generation aircraft to fight into complex IADS. For an in-depth analysis on effects in the Information Environment, see From Electronic Warfare to Cyber and Beyond: How Drones Intersect with the Information Environment on the Battlefield.

Fires: The Infantry Battalion Experiment (IBX) Phase II Final Report concluded that “the [Force Design Infantry Battalion] FDIB was able to sense and use non-organic fires assets to successfully shape the battlespace with integrated sensors and Group 2 sUAS.” (p. 26). Compared to legacy formations, the primary improvement was the ability to extend sensing capabilities and engagement distances. This is precisely where unmanned systems transform fires. While the G/ATOR provides sensing out to 200 km and the NMESIS can strike targets at a similar range, currently available UxS dramatically extend both sensing and strike distances—often at a fraction of the cost and with a substantially lighter logistical tail.

Group 2/3 aircraft can designate targets and hand them off seamlessly

Platforms like the Autonomous DeepFires Launcher are self-driving and fire a variety of payloads to include Tomahawk and Patriot missiles

Leverage one-way attack platforms — e.g., LUCAS, MQM-172 Arrowhead

Ground Organic Precision Strike System (GOPSS) Echelon 0-Air/0-Ground (0A/0G) generates precision effects at the tactical level

USVs should also incorporate kinetic one-way attack options (a concept akin to a kinetic Maritime Reconnaissance Vessel (kMRV)) capable of delivering precision strikes against surface combatants or high-value littoral targets

HIMARS become short-to-mid-range systems once firing batteries begin employing systems like the Barracuda-500

Affixing antennas to UxS platforms, communication ranges expand dramatically, linking dispersed units across littorals and extending fires networks deep into contested areas

Intelligence: The proliferation of sensors in all domains enables the collection of information at a previously infeasible scale. Systems like the JUMP 20, V-BAT, and Stalker (HAVOC config) allow for unprecedented means to conduct ISR-T. The modular payloads and configurations permit a wide variety of missions and tasks. UxS adds exponential speed and scale to the intel cycle.

The Palantir Artificial Intelligence Platform (AIP) accelerates targeting by recommending objectives, validating strike options, automating post-strike assessments, and fusing sensor data with shooter execution faster than human targeting cells can

Palantir’s Meta Constellation leverages AI to direct, synchronize, and integrate commercial and military satellite imagery, drone video, cyber intelligence, and signals data in real time, enabling commanders to identify, categorize, and monitor forces across the battlespace

Force protection: UxS reduces risk to life, force, and mission.

Unmanned overwatch of expeditionary advanced bases, ammunition supply points, and amphibious lodgments detects sUAS threats, guides counter‑UAS interceptors, and documents pattern‑of‑life

UGVs patrol obstacles and tripwires, reducing exposure

USV/UUVs provide early warning sensors in the littorals and kinetic solutions.

Command and control: The Infantry Battalion Experiment (IBX) Phase II Final Report noted that “in its current construct, sUAS feeds end at the ground control stations. These sUAS systems were highly effective in providing domain awareness to the battalion commander.” (p. 23). That finding highlights both the opportunity and the gap. UxS can provide commanders with unparalleled reach, but only if the network extends beyond the ground station. Properly employed, UxS transforms command and control by increasing resilience, connectivity, and real-time awareness through distributed network nodes—turning every unmanned platform into both a sensor and a signal extender. Comm relays that were once marked by large OE antennas have gone airborne.

Through multiple sensors and feeds with systems like COMPASS, commanders can achieve a greater situational awareness and more options to impose friction on the enemy at every phase of the fight

Marine Corps Operational Architecture must leverage automation, AI/ML, and rapidly emerging technologies like Hivemind to unlock human capital and create a resilient, networked ecosystem of UxS across all domains.

UAS integrates Multi-domain Unmanned Systems Communications (MUSIC) mesh network for C2.

Common Multi-Mission Truck (CMMT), a family of compact, low-cost air vehicles designed for a wide range of missions.

The recent MARADMIN announcing Maven Smart licensing for the Marine Corps demonstrates institutional recognition that AI-enabled processing, exploitation, and dissemination (PED) is essential, and the establishment of Project Dynamis resources the effort with the appropriate level of leadership. By automating exploitation, tasking, and fusion, Maven Smart provides the connective tissue to integrate sUAS and Group 2/3 feeds into the COP --generating actionable, real-time intelligence that accelerates targeting and decision-making.

Aviation: The UAS (FOUAS) CONOP offers the value proposition upfront: “enhanced integration of UAS in MAGTF operations to improve situational awareness, lethality, and force protection; proposed reorganization of UAS to optimize flexibility, scalability, and command and control.” As General David Berger noted in the DoN Unmanned Campaign Framework, “Concepts such as half of our aviation fleet being unmanned in the near- to mid-term, or most of our expeditionary logistics being unmanned in the near- to mid-term should not frighten anyone.” This vision reflects the direction in which Marine aviation must head. Testing of the XQ-58A Valkyrie under the Marine Corps’ Penetrating Affordable Autonomous Collaborative Killer – Portfolio (PAACK-P) highlighted the potential for unmanned teammates to expand reach and increase survivability. The unveiling of Sikorsky’s S-70 UAS U-HAWK and Shield AI’s X-BAT, powered by Hivemind, suggests General Berger’s prediction that, in the near-term, half of our aviation fleet may have been a conservative estimate.

Group 2/3 aircraft can assume SCAR-C roles, employ precision glide kits, enable FAC(A), serve in an escort role with non-kinetic effects, and even carry kinetic options that de-risk manned platforms. Together, these roles decrease reliance on a constant flow of manned attack aircraft, lowering cost per flight hour while increasing the volume and persistence of effects delivered per gallon of fuel and per minute of contested airspace.

Conclusion:

In an address to Congress, General Eric Smith, the 39th Commandant, has emphasized that the Corps’ understanding of “maneuver” must evolve alongside the changing character of war: “Marines at the tactical edge will maneuver under all-domain supporting fires to seize terrain and destroy the enemy. This challenge will require a greater proliferation of capabilities that can provide those all-domain effects down to the lowest level. This requirement includes autonomous systems; precision fires; intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and targeting (ISR-T); integrated command and control; and increased ground and maritime mobility.”

The imperative to operationalize UxS for greater lethality and survivability demands decisive action. The Corps’ future success will hinge on agility and adaptability—qualities Marines have always possessed and must now demonstrate once again.

Search and Destroy

SSgt Kaleb Miller

As we look to the future of the Marine Corps, many skeptics question the new mission of the infantry and their place in the new construct. The cause of the skepticism is the idea that an equal-parts traditional war of two forces facing off eye to eye and waging war on one another is the way of the past. Aligned with that was the sunset of the Scout Sniper program and the stand-up of the Scout School, which divested precision fires and reinvested in reconnaissance. Without long-range precision fires, we are left with Marines highly trained in infiltration, surveillance, and threat-armor identification. This leaves the investment the Marine Corps made in these Marines with no return, and focuses them on substituting for unmanned systems that have proven easy to counter during recent conflicts. If we take these scouts and fuse them into a Javelin team, we create a small, highly skilled, highly trained team with endless capabilities. As we transition as a service to LCTs, if there is no longer a requirement for mounted anti-armor capabilities and precision fires, two fields remain available to fill a new role. The transition to Littoral Combat Teams creates an opportunity to synergize existing capabilities.

The National Defense Strategy outlines China as a pacing threat; we turn to the Pacific and reflect on the island-hopping campaign of WWII. A large-scale amphibious assault on island chains is not as feasible when those islands are littered with surface search radars, high-fidelity sensors, and robust anti-air/ anti-ship capability. How do we, as a service, fill this gap for the joint force? A simple answer is to do exactly what we have done in the past: adapt.

In this case, adaptation should mean the standup of search-and-destroy sections consisting of a 6-man searching element outfitted with long-range communications, organic precision fire munitions (OPFM)/ First Person View (FPV) drones, and Small Unmanned Aerial Systems (sUAS), working in conjunction with a 6-man destruction element outfitted with 1 Command Launch Unit (CLU), 2 FGM-148 Javelin Missiles, with one member of the team being a Joint Fires Observer (JFO) or a Joint Terminal Attack Controller (JTAC). This combination yields a small force with a long-range observation and killing capability.

There is as much of a requirement for defensive capabilities as there is for offensive, including a small man-packable Counter Unmanned Aerial System (CUAS) capability to these small teams. The extension of counter-drone warfare would extend the protection of Naval vessels from adversary low-cost drone swarms and attacks. This increase in situational awareness would allow Naval vessels to focus their counter-aircraft systems on higher-yield adversary capabilities, such as manned and unmanned fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft.

General Alford’s original idea for the Hunter-Killer platoon was a step in the right direction and may have even been before its time. His article focuses on a significant change in the current construct, aiming to have a large subset of Marines proficient in a slew of weapons that would provide flexibility to the commander and introduce a reconnaissance and killing construct. Search-and-destroy elements create a smaller pill to swallow for Battalion Commanders, allowing them to allocate resources within the battalion. There are no requirements for a school or funding needed to support this endeavor; funding would be for training alone. The weapons systems are available, the schools are available; the only thing missing is putting two separate capabilities that are lethal, but together are capable of shaping the battle space for the joint force.

The employment of these teams would be offensive in nature, partially aligning with the search-and-attack operations outlined in MCRP 3-10A.3. I say partially because the adversary they would be targeting. Instead of focusing on enemy LP/OPs, they would focus on destroying enemy anti-air and anti-ship capabilities, setting the conditions for the insertion of High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS) and infantry rifle companies into that zone of action. This co-aligns with the Force Design efforts and the Navy’s navigation plan for distributed operations and controlling littorals in support of our Navy’s global sea domination efforts.

During my time with CTU 61.2, I witnessed the true capability of combining multiple capabilities to shape the battle space. After hearing firsthand from commanders regarding the necessity for units to increase maritime domain awareness, it seems the risk is well worth the reward. That said, those efforts were conducted in a fairly uncontested environment. As we continue our experimentation efforts, we, as a service, need to lean into how we set conditions for those systems to be placed and how we can support the insertion of firing agencies that receive target-level fidelity information from the mobile recon units. That gap can easily be filled by Search and Destroy sections with a mission focused on just that, enabling freedom of movement for national-level assets like an ARG/MEU.

The question is how we get those Marines to that island if the adversary has anti-air and anti-ship capabilities. With Marines already possessing the capabilities for actions, there is ample time to develop insertion capabilities, leaving no perfect insertion method for all situations. If the answer is by air, the schooling exists for these Marines to gain that capability. As amphibious assault battalions continue to train on small-boat operations, they create yet another method of insertion. The introduction of the Medium Landing Ships purchased by the USN leaves the door open for an increasingly capable landing capability. As stated, there is no perfect answer for all situations, but the answer will be produced within the commander’s analysis. Identifying the adversaries’ gaps and formulating a plan to exploit them to facilitate the insertion of this small unit will create a larger gap to allow the flow of more troops, ultimately setting conditions for global sea dominance.

When the Commander does his analysis, it is apparent in all wargames that the enemy quickly throws personnel and equipment at problems. With the proliferation of enemy amphibious tanks and other mechanical assets, there is a need to remove those threats at the tactical level. Currently, the only assets available to handle armor threats outside of an infantry battalion are nestled within the operational and strategic asset list. Having the assets at the tactical level enables the main effort of the infantry to conduct operations and facilitate operational and strategic components.

The opposition to this construct lies in a lack of confidence in these small units’ ability to self-sustain and the fear of compromise. As logistics has been a topic of debate at the most senior levels of the joint force, it is no coincidence that it is a conversation among staff noncommissioned officers as well. As we stand today, logistics will remain a shortfall and concern within the forces, and with continued experimentation, I believe we will find our answer. As we sit today, the sustainment duration is in the 8 to 16-day range, with no resupply capability. As far as a compromise by adversary forces, that is where the advantage of a small-footprint unit with a specialty in staying hidden will be emphasized.

Insertion and sustainment are only two-thirds of the problem. Following action or compromise, there is still a question to be answered: how do I get my Marines out of the contested environment? As we examine this issue without reiterating the same lines from the commander’s analysis, I see two schools of thought. Do I have the forces to resupply these Marines during their occupation of these islands, or if the environment does not yet enable the mass movement of troops, how do I get them out? I lean on previous statements regarding the environment, the commander’s analysis, and the team’s extraction capabilities to answer that very question. There is an inherent level of risk assumed by the commander with this concept, but regardless of concept or practice, the issue across the Marine Corps is how to get my Marines in and how to get my Marines out.

In conclusion, there is a gap that we could address with national-level assets and achieve the same end state. The difference lies in the cost, specifically the cost of moving a satellite, the cost of relocating firing agencies, and the inherent risk of placing those firing agencies within the adversary's weapon engagement zone. The weapon systems and associated capabilities of scout and anti-armor teams have been proven repeatedly in combat. Putting them on a team together with a new mission in a new environment, will new technology still yield an exponentially more lethal capability for the joint force and our naval partner in the future fight?

The Written Word

Fiction and Nonfiction written by servicemen and veterans.

Cycle of Violence

Seabass

June 2004

Husaybah, Al Anbar Province, Iraq

Four other Force Recon Marines slept on the dusty floor beside Brian and me as we stood watch, scanning the city from the blasted-out windows of the building’s top floor. Before dawn, our team had secretly occupied the abandoned Saddam-era Iraqi government office, slipping away from the 40-man infantry patrol without the local spotters noticing. Like hunters eager to kill a trophy buck, we searched the alleyways below with high-powered optics, hoping to catch our prey off guard as the sun rose.

Husaybah, a densely packed rat’s nest of a town on the Syrian border, was bursting at the seams with ‘Muj’ - a mix of hardcore foreign jihadists, combat tourists, disenfranchised former Iraqi soldiers, and local opportunists. The savage outpost had a nasty edge, with death so close that a short life span seemed natural. Religion, testosterone, and conspiracy theories fueled a self-sustaining cycle of violence. The deaths of colleagues and slights of honor incited further action. Body counts became scorecards.

Hatred infected everything in this ecosystem. It was heard in the too-long bursts of fire that overheated machine gun barrels. It drove Muj IED makers to work to exhaustion, like obsessed outsider artists in back-alley garages. It motivated our platoon to drop unit calling cards on dead fighters just to send a message. The enemy intensified the hostility by employing car bombs and suicide bombers, and we introduced them to air strikes and thermobaric rockets. Both sides fought like wild-eyed predators thrown together in a small cage.

Little was wasted in Husaybah other than life. During gunfights, the local kids greedily harvested our spent brass ammunition casings as they fell onto the street. The Muj hid IEDs in dead animals. Our platoon snipers, hidden among garbage on the outskirts of the city, maintained a distant watch over the Muj they killed in the streets. The dead enemy were valuable bait to attract more targets who attempted to recover their martyrs.

A few months earlier, our platoon and a reinforced company of infantry Marines deployed here, supposedly intending to safeguard civilians and create conditions for democracy to take root. We soon discovered, however, that the locals, under pressure from the swaggering and ruthless Muj who lived among them, were intractable collaborators. While our senior officers planned reconstruction projects, the operators and grunts passed around well-worn copies of Devil’s Guard and devised ruthless plans. We knew that a successful counterinsurgency first required breaking the enemy’s will.

We grew to despise the locals, and they returned the sentiment in spades. The so-called ‘civilians’ weren’t non-combatants, but accomplices to murder. Our jaws and trigger fingers tightened as the villagers openly laughed, their faces beaming with joy, when IEDs maimed young infantry Marines. The hateful children acted as spotters and threw rocks at us as their parents looked on with approval. We’d see to it that these nasty fucks got the government they deserved.

Our platoon was usually on the receiving end of violence - an unnatural position for special operators. The Muj regularly attacked us with small arms and IEDs before slipping back into the populace. They pounded our base with mortars as we sat pondering the construction of our make-shift barracks. A month ago, an enemy sniper round struck my ceramic chest plate while I held security on the street during a daytime raid. The experience left me with a deep bruise and bouts of dark contemplation.

Four days ago, our platoon volunteered to recover the remains of a beloved infantry company commander killed in action. We felt a responsibility to spare the Captain’s subordinates the trauma of seeing his broken body. Working silently as the sun hammered us, we wrapped a black body bag around the Captain’s mangled corpse, nearly cut in half by close-range machine gun fire. The cheap plastic bag was once the object of the Captain’s black humor every time he jumped into the passenger seat of his command vehicle. Now unfurled, it realized its purpose as a temporary tomb for his dirt- and blood-covered corpse. A heroic soul reduced to an obscene and unnatural pile of flesh.

Early the next morning, our platoon and the Captain’s orphaned company raided homes throughout the city. We hoped to take revenge against the enemy as they hid in their bed-down locations. As the infantry Marines established a cordon around the target houses, our platoon explosively breached and cleared the structures, eventually capturing 14 Muj and recovering a trove of computers, phones, IED materials, and weapons. We preferred to kill, rather than capture, the Muj, but none met our legal criteria for lethal force. When some resisted, however, we rained fists and boots on the cowards who refused to fight us like men.

As our convoy snaked back to base with the detainees, the enemy responded by triggering a rocket from a launcher built into a stairwell 20 feet above the road. The rocket screamed down into the open back of a Humvee where five young infantry Marines were seated as if on park benches. The warhead exploded among the five, slinging dozens of small arrow-like metal flechettes through the air.

As the badly damaged Humvee limped to a stop, two of the Marines crawled over the back of the truck and fell in a pile. Incredibly alive, they were soaked in blood and explosive material. They slowly stood and stumbled aimlessly in the street. The survivors’ three friends, seated close enough to reach out and touch only 30 seconds earlier, were instantly transformed into headless masses as if commanded so by an evil magic wand.

After dwelling a little on these recent events, I refocused and continued scanning the dusty lots and alleyways outside of our hidden position. I was startled from complacency as six Muj appeared from behind a building only 50 meters away. Oblivious to our presence, they stopped at a small open intersection and huddled closely. The fighters wore black running pants and dark shirts, their faces covered with balaclavas and red checkered keffiyeh. Two had bandoliers of machine gun ammunition draped over their shoulders. Another carried a backpack containing extra RPG rounds and AK-47 ammunition. As they prepared for action, most of the Muj bounced up and down in place like boxers waiting for the bell. One was clearly in charge, his arms gesturing like a preacher while delivering instructions to his attentive flock. My heart raced with excitement as I hissed, ‘Enemy 12 O’clock!’ at Brian.

Brian slid in next to me. He took in the scene and whispered, ‘Oh, hell yes!’ while moving his rifle into position. I lined up my ACOG rifle sight on the preacher’s chest, so close that it nearly filled the entire view of my magnified scope. I focused on a stain on his shirt and pressed my suppressed M4 carbine deeper into my shoulder. I told Brian,’ I’ll take the guy in the middle who’s giving orders and then shift to the others on the left. You take the RPG gunner and then move to the two on the right. After that, we’ll improvise…. on ‘three’.

As I counted down to one, I slowly pulled the trigger and felt the break of the shot. The preacher immediately dropped to his knees. I followed him down, firing four more shots into his chest and head in quick succession before he fell into the dirt. After years of training, my actions were mechanical and rhythmic like a slaughterhouse worker driving a bolt into a cow’s head.

I swung my rifle left to engage the other Muj just as Brian dropped the RPG gunner with two well-placed .556 shots to the chest. The report of our suppressed carbines created confusion among the clean-shaven fighters, who couldn’t identify the origin of the muffled shots that echoed among the buildings. During the final seconds of their lives, the remaining enemy scattered like panicked rabbits, unsure which direction led to safety.

Three of the fighters ran directly toward our position and stopped with their backs to us on the street just meters below. They shouldered their weapons and frantically scanned the rooftops across while jabbering in Arabic. Leaning out of the window, Brian and I placed several rounds into the enemy machine gunner and then transitioned to finish off the two other Muj when they turned toward us in a too-late moment of recognition. Brian and I alternated placing fresh magazines into our weapons.

One fighter remained. Still trapped in the middle of the kill zone but hidden from view, he yelled ‘Allah Akbar’ from behind a low wall 25 meters away. We fired at the top of the wall to keep him fixed in place. Realizing that his options were limited, the Muj broke from behind cover and ran left across our field of view. I swung my rifle to engage the fleeing target, led him by a foot, and fired. I missed with the first shot but connected with a solid second shot to his thigh. As he crumpled to the ground, Brian and I rapidly fired several more shots to his profiled chest. The kill zone cleansed of life, we scanned for enemy reinforcements.

The ambush was over in less than a minute. We had decimated the enemy element. The rest of our team, startled awake by our firing, scrambled to throw on gear and move to firing positions.

“Hold security on the other window”, Brian barked to one of the disoriented Marines. “We killed six, but there are probably more”.

“Do you want me to call the QRF?” asked our radio operator, referring to the remainder of our platoon waiting on standby as a quick reaction force back at base.

“Fuck yes.”, Brian responded calmly. “But tell them only to stage just outside the base for now. We don’t need them to come in yet. We’ll need an extract eventually… just not now. Since we can defend this position indefinitely, we’ll stay a little longer and see what happens. Make sure you guys maintain 360 security and watch the stairwell.”

We had certainly lost the element of surprise, and everyone in town now knew we were here. We were secure for the time being, though, and assessed that more Muj would come out to attack to save face. Over the next hour, we remained in sporadic contact as small groups of Muj popped up to fire inaccurate bursts from several hundred meters away. After a few minutes of surveillance, I dropped a black-clad male as he stood on the street staring at our position while speaking into a radio. Although he didn’t have a weapon, it was clear he was spotting for the Muj. I wouldn’t lose sleep over taking the shot.

One of my teammates nailed three more fighters from over 1,000 meters away with his Barrett SASR .50 caliber sniper rifle. I provided corrections for him from behind my spotting scope, which offered a front-row view of the dirty work. Upon impact, the huge SASR rounds, designed to destroy vehicles and infrastructure, took individuals off their feet and left huge gaping exit wounds. I watched with fascination as a mangy wild dog pulled at the flesh of one of the dead Muj. The feasting dog snarled and snapped at other members of his pack as they tentatively approached to share in the prize.

By nightfall, we ran out of targets as the Muj lost the spirit to fight. We were energized, having killed several enemy combatants with no friendly casualties. As nightfall arrived, we carefully departed the building while scanning for hidden IEDs and Muj. With the aid of our night vision goggles, we hastily searched the dead fighters sprawled in front of our former position. We recovered a few cell phones, SIM cards, and ID cards, which would help us target more Muj. After moving down dark alleyways, we linked up with our platoon as they waited in idling vehicles. Cobra attack helicopters, piloted by men who were chomping at the bit to engage the enemy, hovered overhead to cover our extract.

Seabass is a former Force Recon Marine.

The Letter I Never Wrote

Stan Lake

I wrote you letters in high school and college biology classes. I mailed them to you during basic training, AIT, and later, my deployment to Iraq. I fought tears of frustration as we talked over each other on the delayed payphones in the call center. Holidays, birthdays, and anniversaries were all rife with turmoil and raw emotion we couldn’t process correctly. We were 7,000 miles apart, and I was obsessed with the idea of you. Little did I know the burden you carried while being left behind. I had no way of knowing how hard my being at war was for you.

I guess you started drinking during the lead-up to that tour. It began with just social drinks and parties to send me off right. I figured, hell, I’m going to die anyway, I might as well drink too. I didn’t expect it to become a problem for you. I just knew it was never for me. I left. You stayed home. Iraq was a dry country. Our hometown was not.

You drank to numb yourself, to quiet the worry you carried living in the darkness of my absence. Through the distance and discord, we became versions of ourselves neither of us could live up to. I was mission-focused, and you watched the death tolls rise on the news back home. You kept drinking. You’d sneak drinks. You made some mistakes. I found out when I got home that you’d been unfaithful. I lost you and a best friend in one fell swoop—how cliché. I still loved you. Removing you from my life made me carry the phantom pain in that part of my heart for years. You were a vestigial limb that I evolved to live without, yet it always stayed attached to my skeleton.

Before I got married to my now wife, I burned all the letters you sent me. I burned our photos, our memories, our history. I burned my war journals because every page sang your name. I was heartsick that our forever was extinguished. I was more saddened to learn later that your drinking became a disease that ultimately took your life.

I carry a lot of guilt, thinking that perhaps my leaving caused you to slip into substance abuse. Into alcoholism. The cause of death was alcoholic ketoacidosis and liver failure two days after Christmas. Everyone called to see if I was okay. We’d broken ties years earlier, and to me, I lived as if you’d died when I burned those letters. I wasn’t ready for the onslaught of emotions that followed. Was this my fault? Was my deployment the catalyst for your slow suicide?

I didn’t know people our age could be alcoholics. Cirrhosis of the liver, at barely over 40, I didn’t know that was possible. I hated hearing how your mother found you. I cried when I read the toxicology report and death certificate. The images that were painted in those sterile documents seared into my brain, and I burst into tears. I mourned for a life cut short.

Despite our ending, we were close once, and no one deserves to die alone. I still loved you long after the pain of what you did. There will always be a part of me that aches with loss, knowing I played a small part in your demise. You were part of my history, my formation, and one of my best friends before it all fell apart. If I could write you one more letter, it’d be to say I’m sorry—for everything. I’d write to tell you that, despite how you feel, numbing it with substances is a road that only leads to sadness. You don’t even have to go to war to be a casualty of it.

A River Runs Through Helmand

Benjamin Van Horrick

As the sun sets in Helmand, a cramped tent smells of body odor and CLP as the squad begins weapons maintenance.

The lull lends itself to the diversion of choice: movies.

“I want to see a love story.”

“I got just the ticket.”

“Oh Jesus – not another midget porn.”

During the GWOT, external hard drives held America’s cinematic canon in a small, rectangular plastic container, a little larger than a wallet. From the Godfather Trilogy to every Police Academy, the collection brought the motion picture to a province still mostly stuck in the 18th century. The hard drives also held a smattering of smut, each with titles more ridiculous than the last. But deeper in the recesses were films that offered something else — tenderness.

No matter what movie they settled on, when the opening scene rolled, the one-liners started flying.

“Why can’t we watch Fast and Furious?”

“Go to bed.”

Tonight, the platoon had settled on an unlikely flick — A River Runs Through It.

Fifteen minutes into the film, and half of the audience retreated to their racks.

The film depicts a father guiding his sons as they fly fish.

Squad leaders felt the same impulse toward their charges, but could never quite find a way in Helmand. In the film, the boys’ father, a preacher, spoke words the squad leaders might have wanted to offer but could never arrange into a coherent sentence.

As they watch, the Marines are transported from Helmand to Montana. Gone for these moments is the stagnant, smelly Helmand River, replaced for a time by the rushing, pristine Blackfoot River. Every hue and value of brown in Helmand gives way to the lush, verdant Montana wilderness.

The Marines lean back further on their packs and nestle in deeper. The screen lights the faces of the Marines still awake, now drawn into the movie. Even though they have not bathed for days or weeks, they somehow feel refreshed. Seeing a meadow or a stream breaks the cycle, if only briefly, of blistering heat, rashes, decaying boots, and fraying garments.

In the final minutes of the movie, images of the brothers, still young on the riverbanks, bleed into the older narrator’s vision as he prepares his fly and casts alone. A close-up of the older man’s hands as he struggles to tie the fly—yet he persists.

The final line of the movie links us with the old man alone in the river:

“I’m haunted by waters.”

Poetry and Art

Poetry and art from the warfighting community.

“A Warrior Untested” Tara Sutcliffe What is sacrifice without war? I raised my right hand while the nation went to war Volunteered to place my God-given talents on the line for a country whose blessings I longed to honor A warrior’s identity built on the potential for sacrifice. Harrowing headlines told of casualties and courage; Brothers and sisters to my left and right deployed once, twice, three times to fight. I believed my time would come as theirs did to do my part, to prove myself. Month after month, year after year, decade after decade, I stood the watch. Ready. Waiting. My duties quiet and invisible. Body sore from drills, exercises, and training. Eyes strained from reading, writing, and reviewing. Hands buried in rosters, reports, and spreadsheets. Mind numbed from blaring alarm clocks and middle-of-the-night calls. Coffee cooling, untouched. Fluorescent lights flickering overhead. Late to bed, early to rise. Hurrying. Waiting. Sprinting. Analyzing. Planning. Preparing. Rinse and repeat: the cycle endless. But no battles marked my path. No opportunities to sacrifice. No scars. No stories of smoke, sand, or steel. Still, I stay ready for the hour that may never call. Service is not glory, but resolve; a quiet faith in unseen purpose. Can I be a warrior untested? What is sacrifice without war? Perhaps this: to offer your whole self— and be left holding it: steadfast, unused— still ready. Old Men and War Adam Walker I don’t want to go to war. I want to see my garden grow. I want to see the joy my dog feels when I come home and scratch his ears. I want to walk my daughter down the aisle, and I want to hear a grandson yell “papa” with outstretched arms. I want to lie down to sleep at night with a full belly in a soft bed with a woman that loves me even though she shouldn’t. None-the-less, I am going to war. I don’t know the politics, but I know the boys. They are being sent so I too must go. I don’t like it much, but I am bound. We’ll fight hard, not for the cause but for each other. I hope we get to be old men with a garden, but I know some of us will be forever young…as we bleed out in the dark soil of someplace. It will be hard for the old men. How to Write a Prose Poem, a Drill Evan Young Weaver Don’t. Write an essay instead. Two paragraphs, or three. First is the smack in the face with some lightly peppered slights and easy vulgarity. Pull back a bit. Close it out soft, intimate, but at arm’s reach. Like fucking without kissing. Fake your vulnerability just a little bit. First paragraph is done. Second one up. Reference one idea from the first and draw this paragraph all in around it like a sleeping bag not rated low enough for a freezing night. Maybe keep it as cold, maybe create that pocket of warmth for the reader. Either way, time for a few examples, maybe some rules that are more like suggestions, all a little rough, a little unexpected. Snap those paragraphs down like twigs as kindling for a fire, just like the ones thick enough to break by hand but are difficult to. Feel the same pain as you do, as you would feel as you crouch uncomfortably, catch a small splinter, light burn as you tend the first flames. Fit to Fight Cody Lefever Lift a tall, frosted pint: ounces of courage, cold strength. Mugs get heavy when beer is gulped. Pushing down the past with every glass. Damn, it feels good. Knurling is sharp on soft, suds-soaked skin. Nights out drinking to be outlifted. Count reps, not calories. Remembering good times, burying bad. Weight un-racked: yesterday’s bar and today’s. Yellow fluid fills a yellow-bellied man. Glug and grunt, lift cans and bells, shots and steel, at home, saloons, and squat racks between. Pour it down, pick it up. Crush the empty. Grip something: liquid or iron. Solutions to problems, day or night, something to be lifted and let down: booze, weights, myself. Pay in cash and sweat, all the same. The Beast of Burden E.J.M. Perez Give him the weight—he will take it—he must In him repose your confidence and trust, He is not mindless—he accepts On his burden he reflects, A brute he may be—yet A fighter we must not forget, There are but few can do as he Beyond his suffering they cannot see, What drives this man—this Beast The legacy of those deceased, Those with scarred and mangled hands Those who fell in foreign lands, Those who kicked in every door Those who took the weight before. Bestow on him no praise—no glory You are not the author of his story, To do the thing he knows is best To put his mettle to the test, To see the sun on his own dawn The Beast of Burden carries on.

Health and Fitness

Guidance for improving physical and mental performance, nutrition, and sleep.

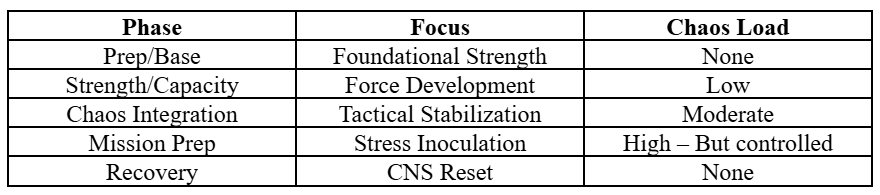

Chaos Training for the Tactical Athlete: Application Within Marine Corps A-IMC Detachment Hawaii

Andrew Siepka, CSCS - Head Strength & Conditioning Coach, USMC WARR Human Performance Center, Marine Corps Base Hawaii

There is a stark difference between training for fitness and preparing for combat. Fitness is predictable. Combat is not. The tactical environment is built on volatility. Surge, fatigue, uncertainty, threat, friction, fog, and life-altering consequences. Chaos finds you whether you invite it or not. In the Marine Corps, especially within high-demand units who attend the Advanced-Infantry Marine Course (AIMC)- Detachment Hawaii, Marines don’t just need to execute under pressure; they need to remain capable, lethal, and lead when everything goes sideways.

Chaos training refers to deliberately injecting controlled instability or unpredictable variables into physical training to force adaptation across physiological, neuromuscular, and cognitive domains. It bridges the gap between conventional strength and conditioning and the uncertain demands of combat (Caterisano et al., 2019; Sayers, 2015). The goal is not simply strength; it is resiliency, defined as sustained performance under disorder, fatigue, and threat.

Why Chaos Training Matters in the Tactical Environment

A Marine must solve problems when they’re tired, loaded down, short on oxygen, sweating through their plate carrier, and having orders barked to them under stress, not just when they’re fresh and working in perfect gym or training conditions. Chaos training reflects this reality by forcing the nervous system and musculoskeletal system to stabilize under unpredictable tension patterns. In other words, it allows the mind and body to “lock in” via stimulation of the CNS.

Traditional training builds strong Marines. Chaos training builds problem-solving fighters, physically, mentally, and neurologically capable under duress.

Neurophysiology and Performance Basis

Chaos training speaks the nervous system’s language. Unstable and unpredictable stimuli increase afferent neural input and proprioceptive demand, enhance motor unit recruitment and co-contraction, improve joint stiffness and reactive stabilization, require rapid sensory integration and executive function, and develop intermuscular coordination and connective tissue resilience (Behm & Anderson, 2006; Kibele & Behm, 2009).

Application Within A-IMC Detachment Hawaii

Working with the Marines of A-IMC-Det Hawaii demonstrated that realism-based training paired with intent produces resilient, adaptable warfighters. These Marines operate in dynamic, maritime-adjacent environments requiring stabilization under load, high-end aerobic and anaerobic capacity, problem solving under fatigue, recoil, and weapon stability, and the ability to perform after exertion.

Chaos training became a core component once foundational strength and work capacity were established.

Example Progressions

- Hanging Band Tension (HBT) lifts

- Slosh-filled carries and sandbag drags

- Reactive med-ball throws

- Decision-based agility

- Unilateral chaos strain

Outcomes Observed

- Increased reactive stability & trunk stiffness

- Better posture and endurance under kit

- Faster reactivity during tactical agility drills

- Enhanced confidence under unpredictable load

Risk Reduction & Injury Mitigation Benefits

Chaos training has a misunderstood reputation in some circles. To those who see instability as a gimmick rather than applied stress inoculation. When programmed responsibly and layered on top of a strength foundation, chaos training plays a key role in injury mitigation.

Key mechanisms include:

• Improved joint stiffness and dynamic stabilization reduces ligament strain risk (Behm & Anderson, 2006)

• Increased neuromuscular coordination limits compensatory patterns that lead to overuse injuries

• Exposure to perturbation prepares connective tissue for unexpected forces—similar to real operational demands

• Enhanced proprioception improves landing mechanics, deceleration, and change-of-direction resilience

• Subjecting Marines to controlled chaos reduces the likelihood they fail under uncontrolled chaos

Marines don’t get hurt because movement is too complex. They get hurt because they are unprepared for complexity.

As the NSCA TSAC literature notes, tactical operators experience high injury burden due to unpredictable multidirectional load patterns, uneven terrain, and equipment stress (Oliver et al., 2021). Strength alone does not protect the warfighter. Stability under stress does.

In a tactical population where musculoskeletal injuries account for the highest non-combat medical limitation and attrition rates, chaos training—applied correctly—becomes not only a performance tool but a force protection tool.

Programming Framework

Chaos should not dominate; it supplements:

You don’t rise to the occasion; you fall to your level of training. Make sure that level includes the unexpected.

References

Behm, D.G., & Anderson, K. (2006). The role of instability with resistance training. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 20(3), 716-722.

Caterisano, A. et al. (2019). CSCCa and NSCA joint consensus guidelines for safe return to training following inactivity. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 41(3), 1-10.

Kibele, A., & Behm, D. (2009). Seven weeks of instability and traditional resistance training effects. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(9), 2443-2450.

Oliver, G.D., et al. (2021). Tactical athlete injury prevention and performance optimization. TSAC Report, NSCA.

Sayers, A. (2015). Tactical strength and conditioning: Preparing the modern warrior. NSCA Performance Training Journal, 14(3), 5-10.

Simmons, L. (2015). Westside Barbell Book of Methods. Westside Barbell.

——————————

This ends Volume 41, Edition 1, of the Lethal Minds Journal (01DECEMBER2025)

The window is now open for Lethal Minds’ forty-second volume, releasing January 01, 2026.

All art and picture submissions are due as PDFs or JPEG files to our email by midnight on 20 DEC 2025.

All written submissions are due as 12-point font, double-spaced, Word documents to our email by midnight on 20 DEC 2025.

lethalmindsjournal.submissions@gmail.com

Special thanks to the volunteers and team that made this journal possible.