Letter from the Editor

The end of one year and the start of another is a natural point at which to reflect, a fact amplified when you consider we’ve been at this Lethal Minds thing for three and a half years.

Three and a half years is a solid lifespan for any start-up, particularly an all-volunteer one, commenced to give a voice to the barracks while making no money to speak of. And we’re still at it, stronger every month. Along the way, some generous folks have seen enough value in what we do to become paying subscribers, which allows us to fund our other efforts. But Lethal Minds Journal is free and always will be. Much of that is because we have some stunningly generous volunteers, most of whom are veterans and active-duty service members. But not all of them, an important fact to note. Some of our most stalwart volunteers are civilians, critical for an outlet that hopes to bridge the civilian-military divide. It’s an essential objective in a country such as ours, in which civilian control is supreme over the military, a relationship that seems to get increasingly muddled in our hyper-politicized nation.

But our main goal here at Lethal Minds Journal will always be to serve as a “for us, by us” platform for junior servicemembers who don’t have a dedicated place in which to be heard. There are plenty of places for senior officers and staff noncommissioned officers to pontificate –Marine Corps Gazette, Proceedings, Parameters, and War on the Rocks, just to name a few, and they’re all great – but though anyone is theoretically welcome in those places, in practice damned few places exist to affirmatively give voice to the folks who take the hills, turn the wrenches, and track the fight. With that said, LMJ has never existed to be exclusive, just the opposite, and it’s been gratifying to see more senior folks who could publish elsewhere offer their thoughts here.

We’ve published hundreds of articles since 2022. Additionally, in the last year, we’ve started publishing longer-form work, sometimes serializing pieces over several weeks. We’ve also established stand-alone series like “12 Questions with a Writer” and “Thoughts from a Vetrepreneur” to highlight the efforts of our community, or at least things we think likely to interest the members thereof. All of that has been internally driven, which makes it a perfect time to ask, “What would you like to see more of at LMJ?”

This is your platform and your voice, designed to serve you. Give us a heads up on what you want more – or less – of. Tell us what we’re doing well or where we’re falling down on the job. Most of all, be a part of it with your ideas, your art, and your stories. Email us at submissions.lethalmindsjournal@gmail.com

Fire for Effect,

Russell Worth Parker

Editor in Chief - Lethal Minds Journal

Dedicated to those who serve, those who have served, and those who paid the final price for their country.

Lethal Minds is a military veteran and service member magazine, dedicated to publishing work from the military and veteran communities.

Two Grunts Inc. is proud to sponsor Lethal Minds Journal and all of their publications and endeavors. Like our name says we share a similar background to the people behind the Lethal Minds Journal, and to the many, many contributors. Just as possessing the requisite knowledge is crucial for success, equipping oneself with the appropriate tools is equally imperative. At Two Grunts Inc., we are committed to providing the necessary tools to excel in any situation that may arise. Our motto, “Purpose-Built Work Guns. Rifles made to last,” reflects our dedication to quality and longevity. With meticulous attention to manufacturing and stringent quality control measures, we ensure that each part upholds our standards from inception to the final rifle assembly. Whether you seek something for occasional training or professional deployment, our rifles cater to individuals serious about their equipment. We’re committed to supporting The Lethal Minds Journal and its readers, so if you’re interested in purchasing one of our products let us know you’re a LMJ reader and we’ll get you squared away. Stay informed. Stay deadly. -Matt Patruno USMC, 0311 (OIF) twogruntsinc.com support@twogruntsinc.com

In This Issue

Across the Force

Presence Over Permission: The Enduring Value of Combat Art

The Written Word

Principles Before Procedures: A working playbook for Marines, veterans, and anyone who learns under pressure

Relief in Place

Moving Forward

Opinion

Part I “Well, I would NEVER!”

Poetry and Art

These Solemn Vows

Iron Sights

Across the Force

Written work on the profession of arms. Lessons learned, conversations on doctrine, and mission analysis from all ranks.

Presence Over Permission: The Enduring Value of Combat Art

Mike Reynolds

Why We Keep Looking Back

Before modern audiences seek to understand wars, they will undoubtedly see a movie about one. For my generation, it was Full Metal Jacket, a Hollywood lens that, for all its fiction, felt more instructive for Marine Corps Recruit Training than any training manual. This instinct to turn to media to understand war is not a flaw; it is a feature of how humans process conflict. But while Hollywood films dramatize, another, older medium is meant to document: the sketch.

The simple act of drawing, of bearing witness with pencil and paper, remains one of the most durable and explanatory artifacts of the military experience. Long after the tactical context of a battle has faded, a simple drawing continues to communicate fatigue, boredom, and fear with a precision that language cannot match. These visual records were never meant to be art for art’s sake; they are a warfighting discipline.

This instinct is neither accidental nor new. From early campaign sketches to twentieth-century battlefield illustrations, militaries have consistently relied on artists to record the human dimensions of war. These images were not created to embellish history, but to stabilize it. They function as a form of institutional memory, preserving aspects of military life that resist reduction into statistics or narrative summaries.

The United States Marine Corps is no exception. For over a century, it has maintained a visual record of its campaigns, training, and people through what is now known as the Marine Corps Combat Art Program. Yet despite the program’s longevity and purpose, awareness of its existence remains uneven, even within the Corps itself. This disconnect raises a fundamental question: if observation-based combat art has demonstrable historical and professional value, why does it remain so obscure to the very institution it serves?

Combat art, when grounded in direct observation and disciplined draftsmanship, functions as a form of professional documentation that reinforces institutional understanding of warfighting. The Marine Corps Combat Art Program endures not because of administrative efficiency, but because the practice it preserves remains indispensable.

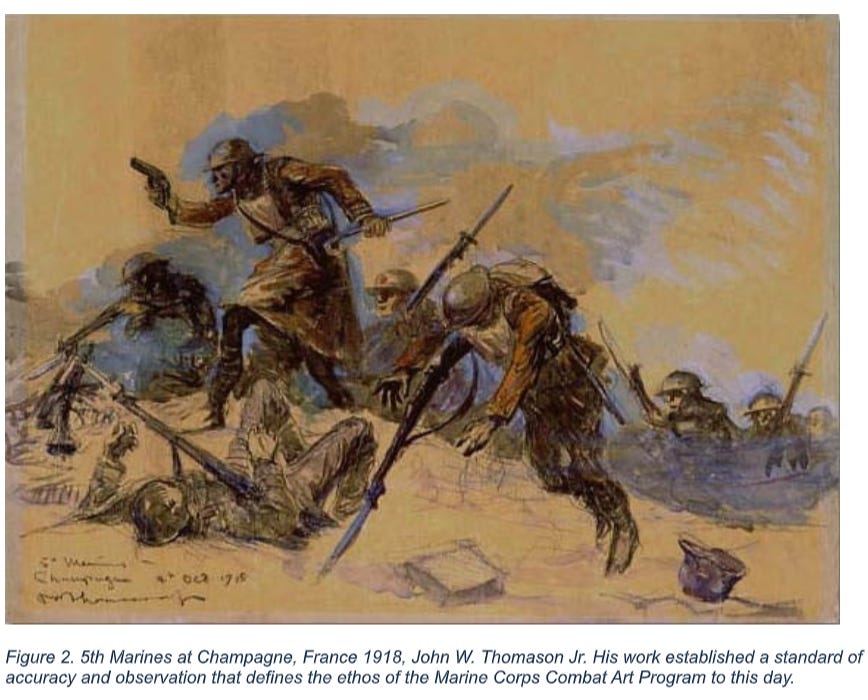

A Standard Established Early: John W. Thomason Jr.

Any discussion of Marine Corps combat art must begin with Colonel John W. Thomason Jr., an infantry officer of the First World War whose legacy continues to shape the program’s ethos. Thomason was neither a detached observer nor an artist temporarily embedded for inspiration. He was a Marine, fully ingrained in combat, who documented his experience through both prose and sketch, producing a body of work that remains among the most respected accounts of Marine combat in the early twentieth century.

His book Fix Bayonets! is frequently cited for its literary merit, but its accompanying sketches are equally instructive. Together, they demonstrate a unified method of documentation in which visual and written records reinforce one another. Thomason’s drawings are not illustrative embellishments; they are observational records capturing posture, terrain, equipment, and interpersonal dynamics that prose alone could not fully convey.

This dual practice established an early standard for Marine Corps combat art: accuracy over spectacle, observation over invention, and participation over detachment. Importantly, Thomason’s example clarifies that combat art was never conceived as an aesthetic exercise separate from military professionalism. It was, from its inception, a method of record-keeping rooted in lived experience.

A Shared Practice Across the Services

The Marine Corps is not unique in maintaining an official art program. The U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard each maintain historical art collections intended to document their service members, environments, and operations. These programs differ in structure and emphasis, but their underlying purpose is consistent: to preserve a visual record of military life that complements written archives.

The Program in Theory and in Practice

I did not learn of the Marine Corps Combat Art Program until eighteen years into active service. This delay was not the result of institutional secrecy, but of institutional silence. Like many Marines, I progressed through multiple enlistments and assignments without encountering information about the program or its application process. If I had seen a sketch or painting on the wall of a chow hall, I would have just presumed it was some random dude hired by the government to paint a picture – I never realized the artists were Marines, expressing their lived experiences.

This realization invites an uncomfortable reflection. How many Marines with the aptitude and interest to document their experiences never learned that the opportunity existed? How many formative experiences went visually unrecorded, not because they lacked significance, but because no one knew to observe them through a visually artistic lens?

The concern is not hypothetical. The Marine Corps prides itself on identifying talent early and cultivating it deliberately. Combat art, by contrast, often relies on individual discovery rather than institutional outreach. This outreach is further hampered when development opportunities, like workshops, remain localized and insular, rejecting modern digital tools that could connect with the global majority of the force. The risk is not merely a missed artistic opportunity but a missed historical record.

The Marine Corps Combat Art Program operates under the institutional umbrella of the History Division in concert with the National Museum of the Marine Corps, where completed works are archived as part of the Corps’ permanent historical record. Officially, the program exists to produce historically accurate artwork derived from direct observation of Marines in training, garrison, and operational environments.

In practice, the program occupies an unusual space. It is neither a traditional military occupational specialty (though a Free Military Occupational Specialty (FMOS) 4606 exists) nor a purely civilian artistic endeavor. Officer participation is currently formalized for ranks from Major through Colonel, while enlisted Marines may be appointed on a case-by-case basis. Eligibility is not constrained by primary MOS, nor does it require formal academic credentials in fine arts.

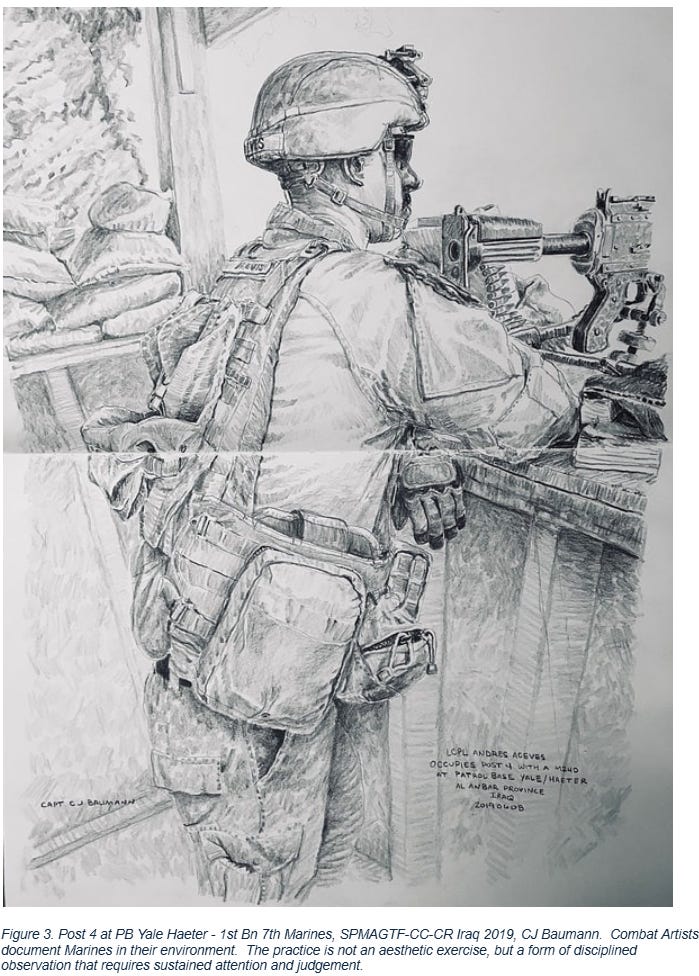

What the program does require, implicitly and explicitly, is discipline. Combat artists are expected to observe carefully, work rapidly under imperfect conditions, and produce visual records that prioritize accuracy over interpretation (though interpretation still adds contextual value). This expectation distinguishes combat art from strategic communication, promotional imagery, or commemorative illustration. The objective is not persuasion, but documentation.

Despite its clear mission, the program’s visibility within the broader Marine Corps remains limited. This obscurity does not stem from a lack of historical precedent or institutional justification, but rather from a tendency for such programs to be administratively peripheral. Combat art persists, quietly, because its value becomes most evident only with time.

Why Combat Art Matters to Non-Artists

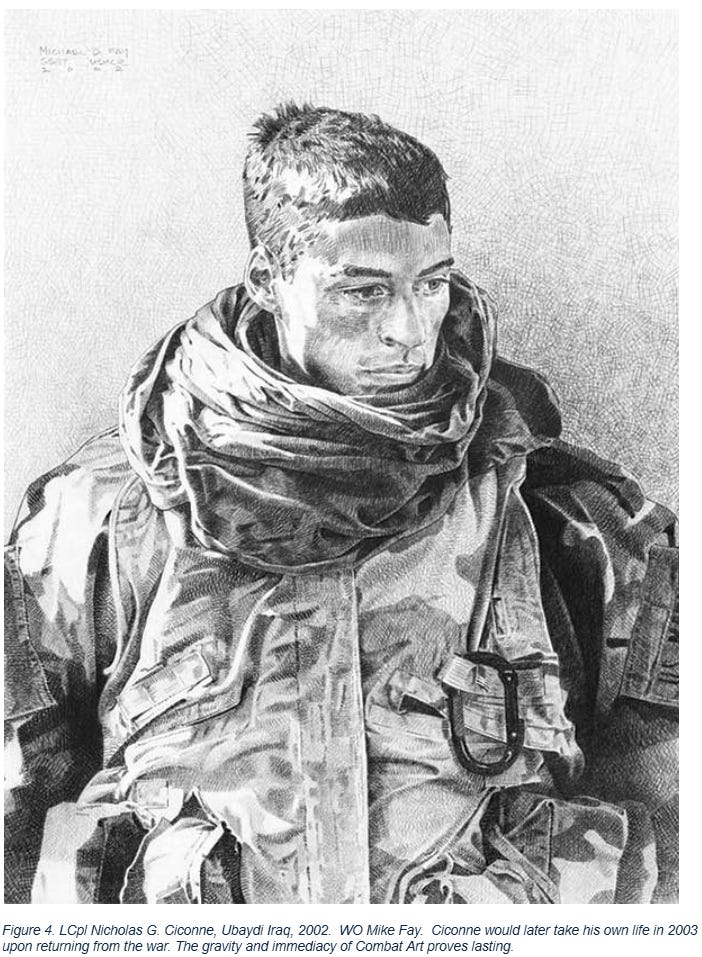

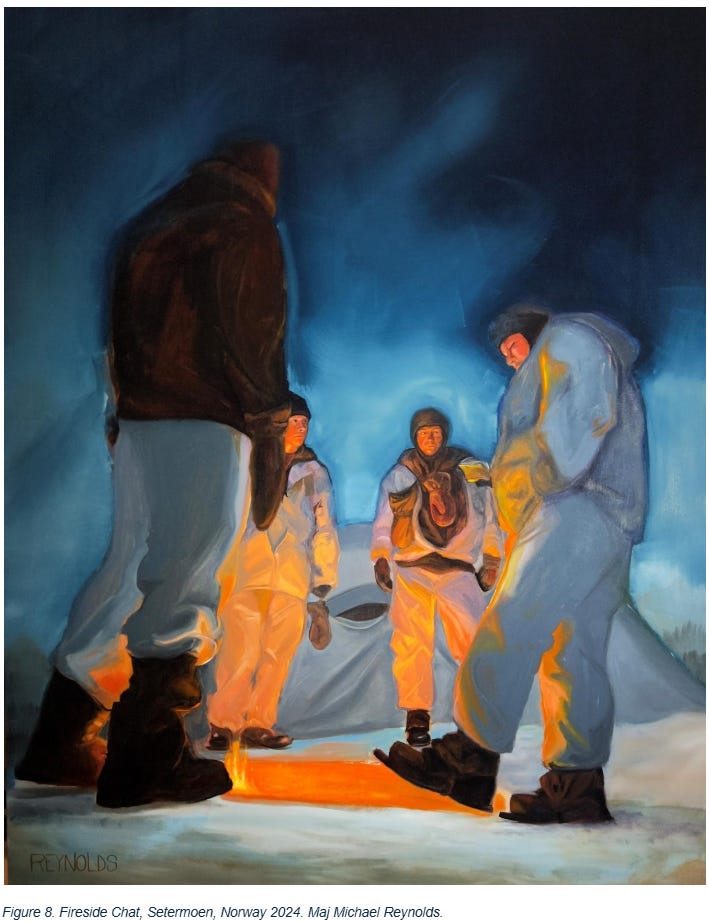

For Marines with no interest in drawing or painting, the relevance of combat art may not be immediately apparent. Yet its value lies precisely in its function as a visual similarity to after-action reporting. Combat art captures aspects of military experience that resist formalization: fatigue during extended operations, the interpersonal dynamics of small units, the physical relationship between Marines and their equipment, and the environmental conditions that shape decision-making.

Observation-based artwork preserves these elements in a way that photography, despite its immediacy, often cannot. Cameras freeze moments; trained observers interpret sequences. The act of drawing requires sustained attention, selection, and judgment, producing records that emphasize what mattered most in the moment of observation.

From an institutional perspective, this form of documentation supports professional education. Visual records offer future Marines insight into how their predecessors lived, trained, and led. They provide context that enriches doctrinal study and historical analysis, reinforcing an understanding of warfighting that remains grounded in human experience rather than abstraction.

What Combat Art Is (and What It Is Not)

Combat art is frequently misunderstood, often conflated with graphic design, caricature, propaganda, or other visual media. These forms serve legitimate purposes within military communication, but they operate under different constraints and objectives.

Combat art is, at its core, observational. It is produced from life and direct experience, and only rarely from secondary reference. How can you describe a watermelon if you’ve never tasted one yourself? The accuracy of combat art depends on the artists’ foundational artistic skills, such as composition, proportion, perspective, and value, to convey what they experienced or saw as they saw it. These skills allow the artist to record environments and interactions as they unfold, rather than reconstructing them after the fact.

This emphasis on direct observation distinguishes combat art from derivative practices. Copying photographs, stylizing figures, or prioritizing narrative effect over accuracy undermines the program’s documentary purpose. Combat art is not concerned with visual trends or personal branding. It exists to record Marines as they are, where they are, doing what they do.

Contemporary Marine Corps Combat Artists

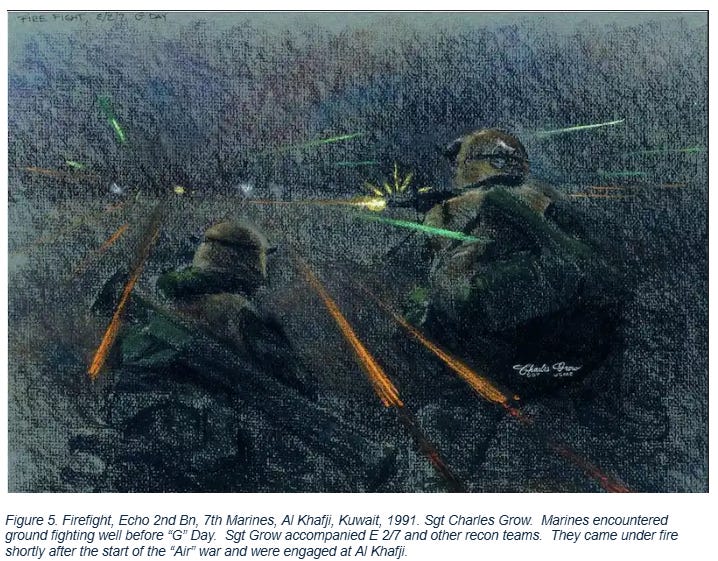

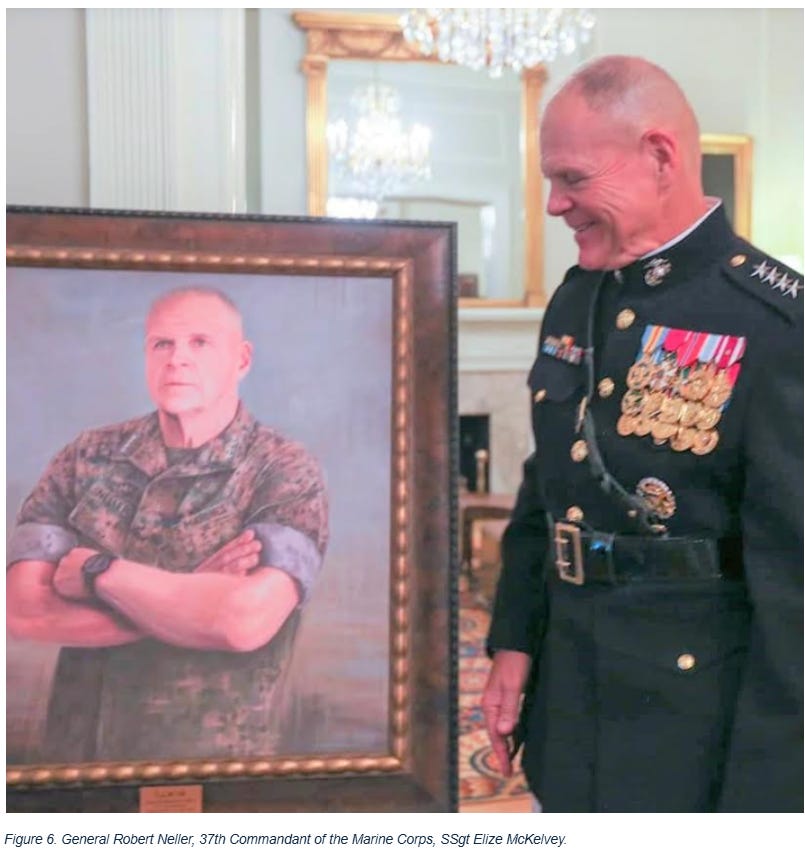

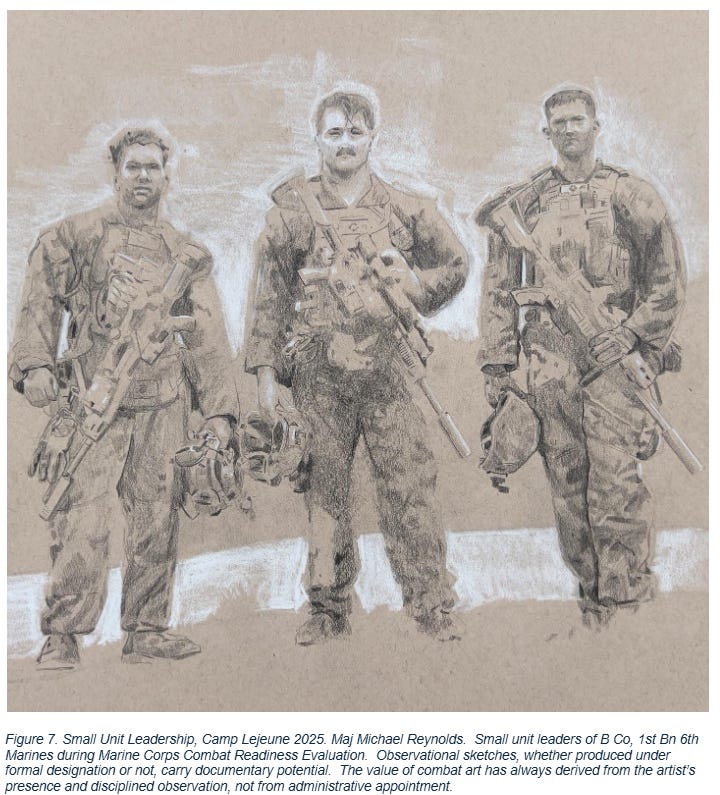

Throughout its history, the Marine Corps Combat Art Program has been shaped by Marine artists who approached the task with professional significance. Among more recent contributors are CWO2 Mike Fay, Capt Charlie Grow, Maj Charles “CJ” Baumann, Col Craig Streeter, and SSgt Elise McKelvey. Their work demonstrates the range of visual approaches possible within the program while maintaining a shared commitment to observation and accuracy.

These artists document not only combat, but training, preparation, and the mundane realities of Marine life. Their contributions reinforce the idea that historically significant moments are not limited to battlefield engagements. Readiness itself is worthy of record.

Access Without Appointment

Marines and civilians who have no desire to apply to the Combat Art Program can still benefit from its output. The National Museum of the Marine Corps provides public access to original works and archives, offering insight into the Corps’ visual history through exhibition. Additionally, reproductions of selected artworks are available through the Marine Corps’ authorized third-party service, requestaprint.com, allowing the public to engage with this record directly.

The Myth of the Gatekeeper: Presence Over Permission.

Participation in the Marine Corps Combat Art Program is often misunderstood as the defining factor that confers legitimacy on a work of combat art. In practice, this distinction matters far less than commonly assumed.

To be clear, the program does not ‘create’ artists. Nor, on the rare occasions it attempts to, does it meaningfully direct them. Its most successful contributors are not responding to guidance, tasking orders, or aesthetic preferences from a higher authority. They are working independently, embedded in their own operational and training environments, observing Marines as they actually live and work. The absence of direction is not a flaw in the system; it is the system’s quiet acknowledgment that authentic documentation cannot be centrally scripted. Conversely, when attempts at formalizing program standards are made, they can become casualties of bureaucracy, with well-meaning reforms indefinitely stalled or farmed out to unqualified confidants, prioritizing personal loyalty over professional competence. This only reinforces the fact that the program’s primary institutional benefit should be administrative, not creative.

Appointment as a “Combat Artist” provides a mechanism through which completed works may be donated to the National Museum of the Marine Corps and accessioned into the permanent collection. This archival function is important, but it should not be confused with authorship, validation, or artistic authority. In other words, the program serves as a repository, not a gatekeeper. This stewardship role is fundamentally at odds with any effort to reframe the program as a private gallery, curated according to the aesthetic preferences of any single individual acting as a de facto director.

This distinction matters. Historically significant combat art has never depended on appointment orders to justify its existence. Its value derives from disciplined observation, technical competence, and proximity to the subject, not from endorsement. The Corps’ visual record has always been built by Marines who were already paying attention long before anyone asked them to formalize the act.

Framed this way, the Marine Corps Combat Art Program functions best when it recognizes its proper role: not as a curator of talent, but as a steward of record. It exists to preserve work that would otherwise disappear into personal sketchbooks, private studios, or forgotten hard drives. The act of donation, not the act of appointment, is what ultimately converts individual observation into institutional memory.

This has an important implication. Marines do not need to be selected, assigned, or titled for their artwork to be meaningful or contributory. A drawing made honestly in a barracks room, a field environment, or a training area carries the same documentary potential as one produced under formal designation. The difference lies only in whether the institution is willing to receive it.

If the goal of combat art is to record Marine life as it is actually lived, then the most important qualification has never been permission. It has always been presence.

The Record Endures

An institution that prizes control over truth will eventually be left with neither. If the goal of the Combat Art Program becomes to curate a comfortable narrative, to act as a gatekeeper against inconvenient or underdeveloped observations, then it will fail its only sacred duty. The Corps will be left with myths instead of memories, with polished statues instead of the tired, dirty faces of the Marines who fought. If we are serious about remembering, then we must get serious about who we empower to do the remembering: the Marine in the field. We are living tomorrow’s history – tell your story to the Marines of tomorrow what you did, through your art if able.

The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not represent the official policy or position of the Department of Defense/War, the United States Marine Corps, or any other government agency.

The Written Word

Fiction and Nonfiction written by servicemen and veterans.

Principles Before Procedures: A working playbook for Marines, veterans, and anyone who learns under pressure

Johnathan A. Wittcop, USMC Ret.

Preface

“From one thing, know ten thousand things.” - Miyamoto Musashi, The Book of Five Rings

I’m a retired Marine, a former Combat Marksmanship Coach, a practicing grappler (BJJ, Judo, Aikido), an amateur scuba diver, and an undergrad in cybersecurity. I’m young in academic years, and I’m not pretending to be seasoned in anything I cite. I’m also not coaching, teaching, or mentoring anyone right now—I’m academically invested and building my own craft. What I do have is a clean pattern that shows up everywhere I’ve trained: when I start with principles—the why—everything I do with the how gets more stable, more transferable, and more reliable under stress. When I skip the why and cling to steps, my skills get brittle.

This paper is for the active-duty Marine who wants something he can use in the barracks tonight, the veteran translating service into a new craft, and the scholar who studies how durable expertise is actually built. It is also personal. Musashi’s way of thinking is the thread through all of it: learn the structure so you can move through forms without being trapped by them.

Where this started (and why it stuck)

Before the Corps, I played fighting games. That’s where fundamentals first clicked. Players who chased flashy combos got smoked by players who controlled space, pace, and timing—footsies, anti-airs on reaction, resource management, and the discipline to press the least button necessary. The wins came from concepts, not button strings.

On the range, I saw the same truth wearing cammies. Stability and natural point of aim, sight picture, breath control, trigger path, follow-through—those aren’t trivia, they’re the anatomy of a shot. If I could name the cause of a miss, the correction would be small and permanent.

On the mat, it repeated itself. A sweep is base and angle beating balance. A throw is the center of gravity crossing a line of no return. A submission is frames and wedges lining force through a weak axis. Techniques multiply; principles stay few.

Underwater, it happened again. I got into scuba while I was still in the service. Trim and buoyancy are stability. Slow, controlled breathing is rhythm. Minimal finning avoids stirring the water column—small input, least disturbance. Quiet checks—depth, NDL, SPG—are sight picture before action. Equipment changes, environments change, but the underlying logic refuses to.

In cybersecurity, I’m still a student. I don’t claim hard-knock experience. I’m learning the field, and the only way to keep up with fast-moving tools is to anchor to ideas: assets and adversaries, attack surface and trust boundaries, defense-in-depth, and clean signal before response. If I can state those plainly, I can swap software and still keep the defense intact.

The thesis in plain words

Teach the invariant first. Use the procedure to show the invariant in action. When the situation shifts, keep the invariant and change the method. That’s the difference between a checklist that breaks outside its lane and a skill you can carry anywhere.

A medieval proof of concept: Giotto’s circle

“…with a turn of the hand he made a circle, so true in proportion and circumference that to behold it was a marvel.” A moment later, Giotto tells the envoy: “Send it, together with the others, and you will see if it will be recognized.” - Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors & Architects.

In the years around 1300, the papal court commissioned major works in Rome, including the decoration of the old Basilica of Saint Peter. Giotto’s reputation was already rising as a break from the stiff Byzantine manner, so the Pope (traditionally identified as Benedict XI, though many popular retellings say Boniface VIII) sent an envoy north to solicit sample drawings from leading painters and report back whom to hire.

When he reached Giotto and asked for proof of skill, Giotto dipped his brush in red and—holding his arm fixed—drew a single freehand circle “so true in proportion and circumference that to behold it was a marvel.” The envoy, thinking he’d been mocked, brought the circle to the Pope along with other artists’ samples and explained how Giotto made it without moving his arm or using compasses. The Pope and his courtiers recognized from this alone how far Giotto surpassed his contemporaries. The tale, Vasari adds, spawned the Tuscan proverb, “Tu sei più tondo che l’O di Giotto!”—“You are rounder than Giotto’s O,” where tondo means both a perfect circle and a dull wit.

The point wasn’t style; it was principle embodied. Mastery of the fundamentals makes every other expression possible. That story lives rent-free in my head because it matches everything I’ve seen: when the base is right, the rest becomes easy; when it’s wrong, you’re decorating failure.

The Conceptual Engine, Spelled Out

Everything I do that holds up under pressure seems to ride the same six rails.

Stability and alignment come first. If the base is crooked, every “fix” injects a new error. Stack your skeleton and a rifle returns to aim; set your hips under your shoulders, and a guard doesn’t collapse; trim out, and you stop fighting the water; architect a network sensibly, and small shocks don’t cascade.

Signal and noise must be separated before action. A clear sight picture matters more than eagerness to shoot. So does clean telemetry before a response. Same on the mat: establish grips and inside frames—signal—before chasing a pass. Acting without a picture wastes effort.

Timing and rhythm govern when force can land. Breath control is timing to the body; anti-airs are timing to the opponent; entries are timing to a weight shift; buoyancy is timing to the inhale; a change window in a system is timing to mission and threat. When the timing is right, effort looks like ease.

Force must travel along the intended axis with the least disturbance. Press a trigger straight to the rear; drive a wedge through the line that actually breaks posture; kick just enough to hold depth; make the smallest configuration change that accomplishes the aim. Big, showy corrections are usually wrong.

Disciplined feedback closes the loop. Hold through recoil long enough to read truth; hold position long enough to feel frames give; stop finning and watch what the water does; verify that a change produced the effect you intended before you stack another one on top.

Follow-through turns feedback into the next clean act. Read, adjust, repeat—without drama. That’s how groups tighten, passes land, dives calm down, and fixes stop turning into new problems.

If I can name these in normal language, I can teach them to a brand-new private, and I can hold myself to them when I’m tired.

What this looks like in the barracks (or a dojo, or a lab)

I start by saying the principle out loud, in words anyone can understand. I show one clean example where it’s obvious. I practice the embodiment without hurry. I change one thing—distance, grip, load, time—and require myself to keep the principle intact. I end by saying three things: what stayed constant, what changed, and what smallest adjustment preserved intent.

On the range that might be dry-fire until the trigger path is clean, then a single environmental change—wind, posture, time cap—while keeping sight picture and press. On the mat, it might be drilling a sweep until base and angle are felt, then adding one predictable reaction from the partner and solving it without abandoning the principle. In the pool or open water, it’s hovering motionless and then adjusting breathing cadence to hold depth without sculling. In cyber class, it’s defining a detection goal and then swapping a data source while keeping the goal, not the tool, as the anchor.

When I assess, I don’t stop at the score. I include a sentence about why it worked or failed, and I retest later—after sleep, after stress—to find out what stuck. Durable skill shows up on a delayed test, not just the first day.

For the active-duty Marine who wants the “So What?”

You already live this. You run PCCs/PCIs because stability beats surprise. You send SALUTE because signal before action beats noise. You move on a lull instead of launching into chaos because timing is a force multiplier. You make the smallest correction that solves the problem because second-order effects are real. You confirm receipt and effect because feedback and follow-through keep intent intact. If you start naming those things deliberately in training, two changes happen fast: your juniors correct themselves sooner, and your AARs get sharper because you’re talking about causes, not just outcomes.

If you want a starting point, pick one block this week—tables, comm checks, maintenance, small-unit tactics—and open by naming the governing principle in plain English. Show one clean example. Change one variable. Close by asking for a short explanation. It will feel a little slower. Watch what happens on the retest.

For veterans crossing into new fields

You already carry these principles. Say them out loud when you interview or when you learn a new craft. Tell a story where you preserved a principle while the environment moved, and how that kept the mission on track. Employers don’t just want tool users; they want people who can keep their head when the script runs out.

For scholars who measure this kind of thing

There’s a clean program of work here. Compare cohorts taught procedures-first versus concepts-first and measure not just immediate performance but delayed retention and adaptation under a single, controlled perturbation. Instrument live settings—range strings, rolling rounds, neutral-buoyancy drills, basic detection labs—to see whether principal articulation predicts successful adjustment. Publish minimal, repeatable lesson patterns so instructors in units, dojos, and classrooms can run them and report effect sizes. Veterans and currently serving Marines are ideal participants; they bring frameworks that can be made explicit, strengthened, and moved across domains.

Edges and honesty

I’m not claiming a lifetime of proof. I’m saying the pattern that taught me to win neutral in Killer Instinct, Mortal Kombat, and Street Fighter taught me to tighten groups, pass guards, hold depth, and keep my head while I learn cyber. In cyber, I’m consciously applying a mindset while I build actual practice. Concept-first training sometimes dents early scores. I choose to make the payoff visible with quick retests and by celebrating small, precise corrections over big, theatrical ones. Not every expert naturally teaches principles; that’s fine. Give them small scaffolds: a one-page concept card, a short demonstration script, a tiny menu of condition changes, and three closing questions—what stayed constant, what changed, what smallest adjustment kept intent.

Why Musashi and Giotto sit on my shoulder

Musashi doesn’t sell gimmicks. He points to invariants. “From one thing, know ten thousand things” isn’t a slogan—it’s a training plan. Learn the structure, so you’re not trapped by forms. On the range, that’s fundamentals over trends. On the mat, that’s posture and pressure over scrambles. In water, that’s buoyancy and breath over motion. In security, that’s models over tools. In all of it, it’s principle over pose.

Giotto’s perfect circle tells the same story from a different century. One stroke, complete control. No decoration, just mastery. Fundamentals first. Everything else—artistry, creativity, expression—sits on top of that control, or it collapses. That’s how I try to train.

Closing

Principles first. Procedures next. Variation to prove it. Explanation to lock it in. Then check again later to see what survived. That’s the whole method.

That is what I owe the Marines who trained me, and the crafts I’m still learning.

Relief in Place

Benjamin Van Horrick

Marjah, Helmand Province – June 2010

“Ramos said his squad wants their cherries popped, sir.”

“Figured.”

“So...”

“Sergeant, can you hand me the CLP?”

“Sir…”

“Larson — we got to do it.”

“And we take them where?”

“We take ‘em to the three-eight…?”

“Are you out of your fucking mind, sir?”

“After the clearing, the Taliban went to ground, right?”

“Right…”

“And their platoon commander and platoon sergeant are at the shura.”

“Until when?”

“1600. Maybe later.”

“So we babysit.”

“So we need Ramos and his squad to go east to get some.”

“You saw that squad. They’re a bag of ass.”

“And we leave tomorrow, the clock is ticking, Larson.”

“But still, sir…”

“What? Better with us than Ramos and those clowns alone.”

Larson laid out everything in his patrol pack, folding threadbare clothing and sorting tactical gear for easy access on a patrol. The rest of his gear and platoon were at Dwyer awaiting a flight out of Afghanistan.

“Larson, how many times do you do this each day?”

“Enough. So you want to head to the three-eight, kick a hornet’s nest, and run?”

“Yup. I don’t see much choice here, Larson. The Taliban went to ground after the clear. They are fucked up for now. Give Ramos and his boys a show.”

Lt Calvert took the gun lubricant, placed three drops on an old undershirt, and ran the rag over the bolt carrier group, leaving a thin layer of solvent.

Calvert and Larson sat now in their tent as transients, not tenants.

Ramos stuck his head into the tent.

“Been looking for you gents everywhere.”

“We turned in our radios, remember?”

“Yeah, so…about getting some.”

“We got the spot for you.”

Larson picked up his laminated map and a map pen from his precise gear arrangement.

“Here.”

“That’s a long patrol; the boys are getting used to the heat.”

“The heat? Deal with it.”

“Ok, hero. Now we’ve got to hump to fuckin’ Pakistan.”

Larson and Calvert shot each other a look.

“Hey, shithead. That clear cost us two of ours,” said Calvert.

“Sir…I didn’t mean…I just…sorry.”

“Just say fucking thank you. Listen more and talk less, Ramos,” said Calvert.

When Ramos looked down at the map, Larson gripped and crumpled the map.

“Ramos, you wanted your cherry popped, so listen to us.”

“Ok...look…so we go here, then what?” said Ramos.

“Take shots and then fall back,” replied Larson.

“Fall back? Fuck that — My boys came to hunt.”

“You are too far east to get support fast. We got caught here before — get shot at and head back.”

“Yeah, and then we look like pussies to the company.”

“It’s a long deployment, Ramos. Business is slow.”

“Fuck…”

“We can do it today. No one else has seen action. Pays to be first.”

“Shit…I suppose.”

“You two going?”

Calvert and Larson locked eyes again. Calvert shook his head.

“We’re in, but…” said Calvert.

“But what?”

“We get the radio,” Calvert insisted.

“No way.”

“Ramos, you’ve never called for fire, nor returned fire, nor been fired at. We got one day and a wake-up, and our ride home. We get the radio.”

Moving Forward

Jennifer Deets

Moving forward can be a physical act – placing one foot out in front, transferring weight to it, releasing the foot behind so it can swing through and be placed in front. Moving forward can also be a metaphysical act – venturing beyond the known, whether cognitive, emotional, or spiritual. Such moving forward is often called letting go or even surrender. Both concepts are tricky for military folks. We don’t like to let go, and we definitely don’t like to give up, to surrender.

If, however, we take “letting go” and “surrender” to mean releasing what isn’t working, what does not further our development and ability to make the world a better place, we start to gain clarity on the power and importance of this kind of moving forward.

My 87-year-old father-in-law has lived a decade longer than he expected to. My mother-in-law lives in a slightly different reality due to dementia. These facts make sorrow a tangible presence in our home as he grapples with his continued existence and all the pains that accompany a body in physical decline and a heart that breaks a little more each time he visits his wife, who is in a memory care facility. He is a prime example of a person for whom letting go would be the gentlest, most compassionate way to move forward as he approaches his final days, weeks, years.

My own father died 24 years ago, my mother almost 6. He was 62; she was 80. He was the healthy one; she had the heart problem. None of it makes sense; it just happened that way. As I approach my dad’s age (I am 58 this year), and I know my heart has the same problem as my mom’s, I wonder which trajectory I will more closely follow.

Whereas my father-in-law wishes he were gone and not suffering (something I do not pretend to understand fully), he has gotten to see his grandchildren grow into adults who are making their own way in the world. They have known him their whole lives, all his stories and advice and love. My dad’s presence in their lives became only stories when they were still quite young, the youngest just a toddler.

The news I got in February about my heart being like my mom’s, and like my brothers’, one of whom had to have a transplant seven years ago, made time seem to stop. Of course, life has gone on, but somewhere in my being I froze, bated breath, eyes wide, afraid. Glacially, I have begun the process of moving forward, past the news and into the world after. In my experience, this forward movement looks a lot like recalibrating what success and accomplishment and a life-well-lived look like. Moving forward means relinquishing ideas and expectations that feel less significant now, even if a lot of time and effort were expended in the acquisition of skills, experience, and degrees that simply do not serve the steps ahead.

I want to be around when I am 87, rickety or not. I want to meet possible future grandchildren and be a living presence in their lives. I want to be a living presence in my children’s lives now. I want to keep living fully, and that means I need to ensure I make room for top-priority activities. Accepting these changed terms is surrendering to the reality of the present moment. Making room for the dreams I have is letting go of the busyness of a life filled with chosen obligations, winnowing them down to the essential few. Letting go, release, and surrender are also taking charge- being the boss of what I can be and striving for equanimity along the way.

As I move forward in my mind and heart, I am ready to move physically into this after chapter, returning to the level of activity that serves the dreams, allowing me to appreciate what is and not fret so much about what could be or might have been.

Opinion

Op-Eds and general thought pieces meant to spark conversation and introspection.

Part I “Well, I would NEVER!”

J.D.

If the all-volunteer military is a microcosm of the society it serves, then we need to acknowledge some uncomfortable truths:

1. Society in America right now is polarized by sensationalist media sources [this piece is focused specifically on this topic and the harm it causes].

2. The Marine Corps (allegedly, just go with it) specifically recruits bold and audacious people with a bias for action. It trains action before understanding because in war, immediate action can save your life before you will ever understand the nuance of the situation you’ve found yourself in.

3. We, as a nation, are in a strange blend of inter-war and cold-war periods that is not good for keeping the military focused on military things, which has led to a surge of “influencers” and people prioritizing anything other than warfighting.

On the topic of polarization—it’s more than clickbait, it’s more than right or left wing, it’s a human issue, and it’s deeply unsettling how many folks will make snap judgments, anchor down, and never update their stance with new information. And what’s worse is some days I am one of them (ask me how I feel about the average field grade). I know very few people who enjoy being wrong, who relish it and seek it out; the military certainly does not encourage it. There is a need to create distance between things we as individuals find ugly, unpleasant, repulsive, wrong, etc, and ourselves. The inherent need to be seen as good can sometimes overpower any other rationale. I remember learning the story of Peter denying Jesus as a child and almost immediately wanting to denounce Peter, to persecute him viciously. How could anyone do such a thing? How could you be so cowardly? Have you no sense of shame? Of right and wrong? And yet Jesus still loved Peter. Whether you believe in God or not, I use that example because 1. It is familiar to me and 2. It has many good principles. I believe the Bible is full of helpful anecdotes of ways to behave that are worthy of emulation and some that are not; whether it is fact or fiction makes no difference to me. If I were more educated, I could almost certainly pull out similar excerpts from the Quran, Torah, Bhagavad Gita, or Native American folktales. My point with the parable is two-fold: I, as a human being, was deeply uncomfortable with the notion that within me, made of the same flesh and bone as all of you, could be the capacity to be such a little shit. And the quickest way for me to expand the distance between Peter and me was to persecute him as violently as possible by enumerating all the reasons why he was wrong to behave in such a way, almost all of which were certain to be valid reasons… And yet, somehow, he was forgiven, retained amongst his friends, and is still remembered by members of the Christian faith as someone worth emulating. Not every mistake is irredeemable, not every choice is unforgivable.

What the hell does that have to do with the military? Ever been in an operational planning team on a general officer-level staff? Ever look around the room when the unpopular person talks? Ever see a hated person make objectively excellent points and immediately be disregarded because… they’re the person no one likes? You either want to win or be right. Sometimes you cannot be both. When you are incapable of compromise in pursuit of winning, you are the problem. And if you have zero self-awareness, you will ruin progress. Looking around at peoples faces, knowing my own face and feeling my eyebrow raise when someone makes a comment I do not violently agree with, I wonder if we are slow to adapt and overcome because the challenges we face are hard or because we are so practiced at getting in our own way through the time we spend on social media swimming within Big Data’s pre-programmed streams that we could not fight our way out of a wet paper bag much less a sUAS battle.

We, as a society, hold many excellent collective values. Almost every nation agrees that things like murder, rape, and any crime involving a child are wrong and that offenders must be punished. And yet within each nation, we find examples of humans exercising their discretion in ways that make allowances for such things—gulags and disappearings, chai boys, and human trafficking all happen regardless of written laws and conventions. That does not make it okay, but it does make it a reality. Evil will always exist in the world. When governments attempt to remove free will and control people to prevent such crimes from occurring, they inevitably create a set of conditions that they believe in so fervently that it justifies in their minds any crimes they will commit to maintain that control. Perhaps you have heard of a well-intentioned (some believe) man named Mao? And, at great risk of losing most of you who are still reading this, perhaps you remember the way our forefathers treated the natives when we arrived and expanded our territory, and formed our nation?

What makes America an amazing place is the amount of liberty the citizenry is allowed to take in how we act. Being belligerent with that freedom is not how we guarantee its longevity; ostracizing those who have different beliefs or lifestyles is not how we cultivate trust. It is not for me to decide if the ends justified the means in Mao’s actions or that of Americans when we pushed Natives off their lands, the part of me that is capable of being a cowardly little shit is happy I was not there to have to decide, but I am terrified by the possibility that I could easily make the same choices with the same information.

Hermann Hesse wrote, “If you hate a person, you hate something in him that is part of yourself.” Creating distance between ourselves and others has led to so much unnecessary bloodshed. Grossman talks about it in On Killing, and anyone who has studied killing or gone through boot camp/military indoctrination is familiar with it. Screaming “KILL” while completing a facing movement is pathetic, but it opens the door to ingraining it as a basic task. As middle management disregards input from those on the ground doing the actual work because their emails have grammatical errors, or they don’t share the same hobbies, or they party too hard on the weekend, we betray our duty to the mission. Moving from unconscious incompetence to conscious incompetence requires us to admit to ourselves that we don’t like certain people sometimes, and we have to forgive ourselves for that to get to the why. And once we figure out why we don’t like or trust someone, we can evaluate whether their input will help drive us toward mission accomplishment. The next issue is speed. How fast can you move through this cycle? Acknowledging the potential for mistakes is not the same as believing you are destined to always commit them. Paralysis by analysis has plagued decision makers for ages, from groups of friends spending two hours deciding where to eat to military commanders deciding where to commit forces and politicians deciding which way to vote. The binary fear of “I have to get this right, or it’s over” has not proven to be useful all the time.

History is replete with figures who were doing their absolute best and really blew it. Anyone who owned a slave or tolerated those who did has since been labeled many a terrible name (once again, for what are all conceivably very good reasons), generals who misplaced their troops and had them killed in vain, politicians and diplomats who knowingly withheld information or misrepresented ground truth to accomplish their own aims at the expense of the people they were installed to protect and support. Police officers who killed a suspect without proper cause or authority. The list could go on for pages, hours, days, even. The bottom line is, in this, the fabric of our shared human experiences, we have some torn threads, some loose seams, and some stains that can never be washed away, but that is no reason to burn the entire garment and dip everything in black dye and start sewing again with only one kind of thread. Hitler tried that, you may recall, as did every member of the Crusades, and it did not end well. Being good to others does not mean whitewashing their shortcomings. We must hold our friends, adversaries, and ourselves accountable while still giving grace and leaving room for recovery. We must engage those who hold different beliefs from us in meaningful dialogue and find common ground—in and out of uniform. The desire to label someone at first glance of their social media profile or within the first five minutes of talking is incredibly tempting, but so harmful to the goal of uniting us at a time when we need unity. The unwillingness to challenge and change our own beliefs is as harmful as having none at all. The People’s Republic of China wants nothing more than to see the downfall of capitalism and democracy and the installation of communism in as many nations as possible. Each time we take our freedoms and liberties and use them to belittle, take advantage of, marginalize others, or do anything else that is objectively mean, we reinforce the belief that freedom is bad, dangerous, and can lead to no good to those who would do us harm. We must not give our nation’s adversaries such easy access to ammunition. We must remember that we, the United States of America, are where the PRC steals the most intellectual property from, where they seek to educate their future leaders, where they send anyone who shows promise in any field in life. They denounce us, but they still see the good we offer; we must not forget that, despite all our internal turmoil, people still long to come to America and live a dream many claim died long ago. We are all capable of screwing things up in galactic proportions, but we are not doomed to, and we cannot corner others into believing they are doomed to either.

Poetry and Art

Poetry and art from the warfighting community.

These Solemn Vows R.H. Booker I will achieve the only true aristocracy, that of consciousness. I will walk the hundreds of miles required to satiate the soul. On the Summer solstice, I will go to the forest and dance the longest of days. If I am to accompany a family of otters out to sea, then so be it. Perhaps this may be on the furthest reaches of sanity but maybe not. In a one-man tent during a rising tide I promised these solemn vows– to listen to the bend of each river, to sing as long as I am taken out to sea. Iron Sights Evan Young Weaver Side to side and don’t see the same, as shoulders touch, eyes do tricks, each keep their own as theirs. Like trying to pick the same duck, as the dozen dive and surface. For all the flights from and to, just fumes and grey and cold. Stacked up on Highway 1, colors blur and merge into one. Even the names are gone, of airbases in Germany, only cold terminal benches remain. Just a fence line is all that is left, of the Epic of Manas. Kandahar, just down to the dust. All of Kuwait, one glance from a veiled face. But flashes back, how a glove feels; another shift, broken, bare hand, and again, another hand in mine. A Soviet tank and a few Enfields, in the pattern of a rug, Lapis blue dyed through the middle, and brown intersects with red. Side to side and don’t see the same, as shoulders touch, eyes do tricks, each keep their own as theirs. Unforgettable, but forgotten, nothing more unique, moondust, clay mud concrete – countryside. I don’t recall one brick, as it is mortared in place. Touchdown and wheels up are the same. The overload and nuance, a glance up from the sights.

——————————

This ends Volume 42, Edition 1, of the Lethal Minds Journal (01JAN2026)

The window is now open for Lethal Minds’ forty-third volume, releasing February 01, 2026.

All art and picture submissions are due as PDFs or JPEG files to our email by midnight on 20 JAN 2026.

All written submissions are due as 12 point font, double spaced, Word documents to our email by midnight on 20 JAN 2026.

lethalmindsjournal.submissions@gmail.com

Special thanks to the volunteers and team that made this journal possible.

As a lifelong student of war, warfare, military history and its art and science - who despite 8 months at Fort Knox School for Boys decades ago has never served in uniform abroad - I have found the traditional arts of painting, sketching, photography, and poetry, a great help in trying to deepen and broaden my own understanding. I have about 20 shelf feet of books about these arts including many by individuals who themselves were soldiers (and that includes their musical contributions). Highly recommend this area of endeavor both for those in uniform and those trying to better understand those in uniform.