Letter from the Editor

I was writing an editorial about the document I carry every day, along with my watch, wallet, keys, and Les George Protech SBR, when it occurred to me: some guys already said it better than I can. Plus, it seems like some among our number, most of whom swore to defend it till death, might need a reminder. So, I give you the…

The U.S. Bill of Rights

Amendment I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Amendment II

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

Amendment III

No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

Amendment IV

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Amendment V

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

Amendment VI

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

Amendment VII

In Suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any Court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

Amendment VIII

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Amendment IX

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Amendment X

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

Maybe you have thoughts on the foregoing. You damned well should. Offer them here. We want your thoughts, opinions, and creativity. Submit them to lethalmindsjournal.submissions@gmail.com.

Fire for Effect,

Russell Worth Parker

Editor in Chief - Lethal Minds Journal

Dedicated to those who serve, those who have served, and those who paid the final price for their country.

Lethal Minds is a military veteran and service member magazine, dedicated to publishing work from the military and veteran communities.

Two Grunts Inc. is proud to sponsor Lethal Minds Journal and all of their publications and endeavors. Like our name says we share a similar background to the people behind the Lethal Minds Journal, and to the many, many contributors. Just as possessing the requisite knowledge is crucial for success, equipping oneself with the appropriate tools is equally imperative. At Two Grunts Inc., we are committed to providing the necessary tools to excel in any situation that may arise. Our motto, “Purpose-Built Work Guns. Rifles made to last,” reflects our dedication to quality and longevity. With meticulous attention to manufacturing and stringent quality control measures, we ensure that each part upholds our standards from inception to the final rifle assembly. Whether you seek something for occasional training or professional deployment, our rifles cater to individuals serious about their equipment. We’re committed to supporting The Lethal Minds Journal and its readers, so if you’re interested in purchasing one of our products let us know you’re a LMJ reader and we’ll get you squared away. Stay informed. Stay deadly. -Matt Patruno USMC, 0311 (OIF) twogruntsinc.com support@twogruntsinc.com

In This Issue

Across the Force

Generative Logistics: The Application of Artificial Intelligence Automation to Tactical-Level Logistics

From Incidental Operator to Professional: Recommendations on Drone Training and Employment

No Bench, No Game: Reconstituting Special Operations Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Depth from the Reserve

The Written Word

Let It Rip

Tolstoy's First Deployment

Opinion

The Kessler Vulnerability

Poetry and Art

Bagram

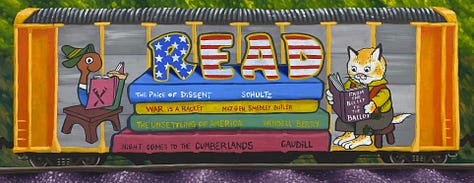

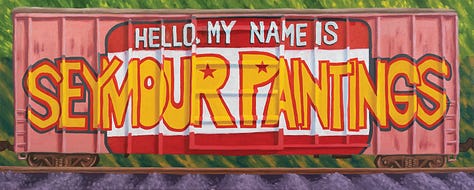

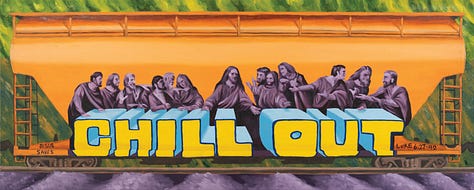

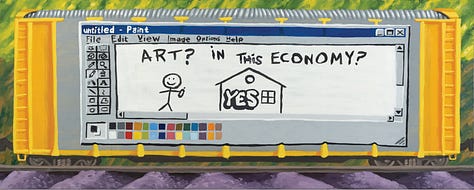

Traintings

Book Review

The Raider: The Untold Story of a Renegade Marine and the Birth of U.S. Special Forces in World War II

The Ambition of H.R. McMaster

Across the Force

Written work on the profession of arms. Lessons learned, conversations on doctrine, and mission analysis from all ranks.

Generative Logistics: The Application of Artificial Intelligence Automation to Tactical-Level Logistics

Captain Bryson Curtin

Throughout the 20th Century, American military strength and dominance has relied on technical and tactical advancements born of a union between the scientific and military communities. As we progress through the quarter mark of the 21st Century and are again engaged in Great Power Competition, we face a renewed need to maintain a technological advantage over our enemies, specifically the People’s Republic of China. While there are a number of research areas that could be called our new Manhattan Project, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is chief among all new frontiers. Although the United States initially achieved an edge in AI, our arrogance, fear, and inability to refrain from committing an “own goal” have allowed us to slip behind the PRC. Earlier in 2025, China released its Deepseek AI model, which is allegedly faster and cheaper than those from American firms such as OpenAI, X AI, or other such entities. This was a wake-up call to many that the United States can no longer sit behind the comfortable quad of Wall Street, the Ivy League, the Capitol Beltway, and Silicon Valley, self-assured in its preeminence in scientific matters. While “Artificial Intelligence Integration” is almost as ubiquitous a buzzword as “tranche” in the Pentagon, integrating AI into military tasks is very much an issue needing focus. As with the original Manhattan Project, the operative question is not so much teaching a computer to think (splitting the atom) but how effectively to apply thinking computers to practical defense problems, including logistics.

It is helpful to lay down a baseline understanding of AI before going further in the analysis. AI is a branch of computer science that enables machines to mimic human intelligence, including learning, reasoning, and decision-making. AI systems begin by receiving large volumes of data through various inputs such as sensors, text, images, or user interactions. This raw data is preprocessed and fed into algorithms that identify patterns, correlations, or anomalies. Machine learning models, a key subset of AI, are trained on labeled data to recognize features and make predictions or classifications. As the system is exposed to more data, it refines its understanding, often improving its accuracy over time. Interpretation and understanding in AI involve organizing data into meaningful insights. Natural language processing (NLP) helps machines understand human language, while computer vision enables the recognition of visual inputs and data displayed on a screen. These capabilities rely on neural networks and deep learning models that mimic the human brain’s structure.

While some AI tasks are automated completely, AI systems are divided into two formats: Human in the Loop and Human Out of the Loop. In Human-in-the-Loop systems, people are involved in supervising, training, or making final judgments, which is important for high-risk or ethical decisions. In other words, an AI model may automatically sift data, analyze it, and prepare a series of decisions for humans to validate, speeding up processes and potentially minimizing or eliminating errors. Human-out-of-the-Loop systems, on the other hand, operate autonomously, offering speed and efficiency but with reduced oversight, raising concerns about accountability, bias, and control. A Human out of the Loop system will be given the order to initiate and/or monitor a task or tasks to produce a certain outcome and carry that order out without the need for (or benefit of) human input.

AI can dramatically simplify logistics planning operations by streamlining complex processes and reducing the cognitive load on planners and operators, specifically by automating redundant or routine tasks, in essence creating a series of simplified decisions and inputs for users to make. One particularly effective application is within systems like the much-maligned Global Combat Support System (GCSS), where AI can be used to automate time-consuming tasks such as form filling, requisition requests, and consumption tracking. By embedding AI into these systems, logistical decision-making can be transformed into a much simpler, user-friendly interface—reducing a potentially multi-step process into a binary prompt like, “Do you want to order more of X? Yes, or no?” This simplification allows operators at the tactical edge to focus on mission execution rather than navigating clunky or redundant data entry. AI can learn from patterns in supply consumption, predict resupply needs based on operational tempo, and automatically populate forms with accurate, validated data. These capabilities reduce errors, speed up the logistics cycle, and increase responsiveness. AI can also help logistics planners analyze trends across units, anticipate shortages, and propose efficient distribution plans. For example, a motor transport unit that has consistent issues with parts breakdown in the JLTV that affect readiness could employ an AI model to analyze all of the reported statuses in GCSS, how often trucks are broken down, the amount of time between parts being ordered and the amount of time of their journey to the unit, the amount of time it takes before the trucks are reported as operational again, and the number of parts needed. The AI model could take all of this information, analyze it, and produce a simple decision to automate the orders process that would look like a prompt of: “Every 44.6 days, this unit has a vehicle become deadlined due to a failure of system X, which is caused by Y part based on current and historical work orders in GCSS. Would you like me to set a recurring task to order Part Y every 31 days so that on the average day that the JLTV breaks down, the part is on hand or on its way already?” The user could then simply say “yes”, and the model would carry out the task until told to stop, or the user could say “no” and issue more direct or limiting instructions to the model, such as “Order the part only on command by me but prompt me every 31 days so that I can take into account the Unit’s budget”. This could all be done in less than a day, automating a simple task that eats away at a unit’s man-hours. By integrating predictive analytics with simplified user interfaces, units can significantly improve sustainment planning and operational readiness while minimizing administrative burden on small unit leaders.

AI’s predictive and analytical powers can supercharge the sustainment planning of units at multiple levels and across stages of the Military Decision-Making Process and other such planning processes and considerations. In crisis scenarios or environments with degraded or intermittent connectivity—such as expeditionary operations, ships at sea, or combat zones—AI-enabled systems can fall back on probabilistic models like Monte Carlo simulations. These models can simulate thousands of possible outcomes based on historical data, previous order cycles, and mission profiles, allowing units to anticipate demand across multiple variables (e.g., operational tempo, geography, failure rates of specific levels of equipment, and stock expenditures). Additionally, they allow planners and staff to adjust certain elements and variables to wargame with greater speed and breadth, such as an unexpected loss of fuel access or an increase in maintenance failures due to fatigue and other human factors.

With these analytical models preloaded and updated periodically during planning cycles, logistics elements can maintain intelligent supply flows even when real-time communication is limited. This allows units to handle their own data gathering and synthesis portions of logistics planning, freeing up the commander’s time and the bandwidth of higher staff sections to focus on the application of that data and the overall commander’s intent. The net effect is a logistics network that is more resilient, responsive, and adaptive. This is not about replacing Marines but about enhancing their capability with tools that manage complexity at scale—especially in contested or resource-constrained environments where efficient use of bandwidth, time, and manpower is critical to mission success.

In addition to the inventory control and planning sides of logistics, AI can also be used to significantly enhance the quality and timeliness of financial and supply analytics available to commanders, inspectors, and supply personnel. By automatically aggregating and analyzing logistics data across multiple touchpoints, AI can generate detailed insights that go far beyond simple dollar amounts. For example, AI systems can track and report the average time it takes for an item to move from delivery at the unit to being sorted, placed into layettes, and finally stored in the correct location under the right supply account. These metrics offer a clear picture of process efficiency, highlight bottlenecks, and expose areas where accountability or procedural delays may be affecting readiness, whether due to human error or systemic supply chain issues. For commanders, this information can inform resource allocation, manpower usage, and unit performance. For inspectors or auditors, it creates a real-time, data-driven audit trail, reducing reliance on anecdotal evidence or manually compiled reports, and can even change a dreaded “finding” on an inspection into a simple, actionable solution that units can input in real time. Over time, patterns can emerge— trends in supply delays, excessive handling times, or inventory mismatches—enabling corrective action before issues become systemic. Ultimately, AI doesn’t just make supply chains faster or simpler; it makes them transparent, accountable, and more tightly aligned with operational goals and fiscal responsibility.

While the points I have described may frighten some or make some assume that AI is currently on the cusp of perfectly replicating human capacities and taking jobs from Marines, those fears are not at all well-founded within the realm of what is technically possible at this writing. AI in its current form is a great tool for analyzing and synthesizing mass amounts of data. It only knows what data it is fed and does not take into account other general probabilities it was not told to consider, such as the presence of natural disasters, changes to funding, or the increased or decreased risk of a crisis in geopolitics such as major wars or a pandemic. Frankly, AI systems are frequently only as good as the data fed into them or the person tasking them, meaning humans will very much be required to be in the loop. Government agencies already know this and are racing to learn to use AI, a prime example being the Department of Defense’s own Project Maven, which has been used to synthesize and interpret UAS and other gathered intelligence data by the US Army’s 18th Airborne Corps.

AI integration is not something that “could” happen or “might” happen; AI integration is already here. However, AI is not by any means ready to replace human beings, nor do we want it to. Human-in-the-loop decision-making will be essential to military operations for the future of AI integration. And while AI cannot fully replace a human being, it can and should be utilized and exploited. No technology is perfect, and all have their weaknesses. But it is helpful to think of AI as something analogous to prior innovations in technologies with profound military applications: aviation, the submarine, the machine gun. Just as the Maxim Gun gave the firepower of a company to a three-man crew, AI will empower single individuals to produce the work of many. If we fail to incorporate AI across as many warfighting functions as possible, we will lose the next big fight—and our heirs will judge us as we now judge those who refused to evolve on the Western Front in 1914.

From Incidental Operator to Professional: Recommendations on Drone Training and Employment

LtCol T.K. Schueman

The Marine Corps is moving quickly to integrate small unmanned aircraft systems into infantry formations. That urgency is warranted. What is not yet settled—and what will ultimately determine whether this effort succeeds or fails—is where these capabilities belong, who should operate them, and what tasks they should actually support.

We cannot continue treating Group I ISR and attack drone operation as incidental skills for 0311s. Doing so is not additive; it is subtractive. The current approach assumes infantry Marines can perform ISR and attack drone tasks incidentally, without those responsibilities detracting from the formation’s combat power. That assumption is flawed. The infantry squad is already fully tasked and undermanned. During OEF, we cross-trained infantrymen to sweep for IEDs. Those Marines could technically operate the equipment, but they were not nearly as proficient as combat engineers performing the same duties. We must learn the lessons of GWOT and understand that just because you can ask a grunt to take on an additional duty does not mean you should.

The current trajectory is increasingly clear: we are attempting to solve a force design problem with a training workaround. We are standing up central and regional hubs to train attack drone operators, pushing that training onto infantry Marines, and then returning them to their units as incidental drone operators alongside their primary MOS duties. The Corps is also sending infantry Marines to TALSA to qualify them as Group I ISR operators. This tax on the rifle squad is not sustainable. It is neither scalable nor operationally sound. If we continue down this path, we will not build a drone-enabled force—we will cannibalize our infantry.

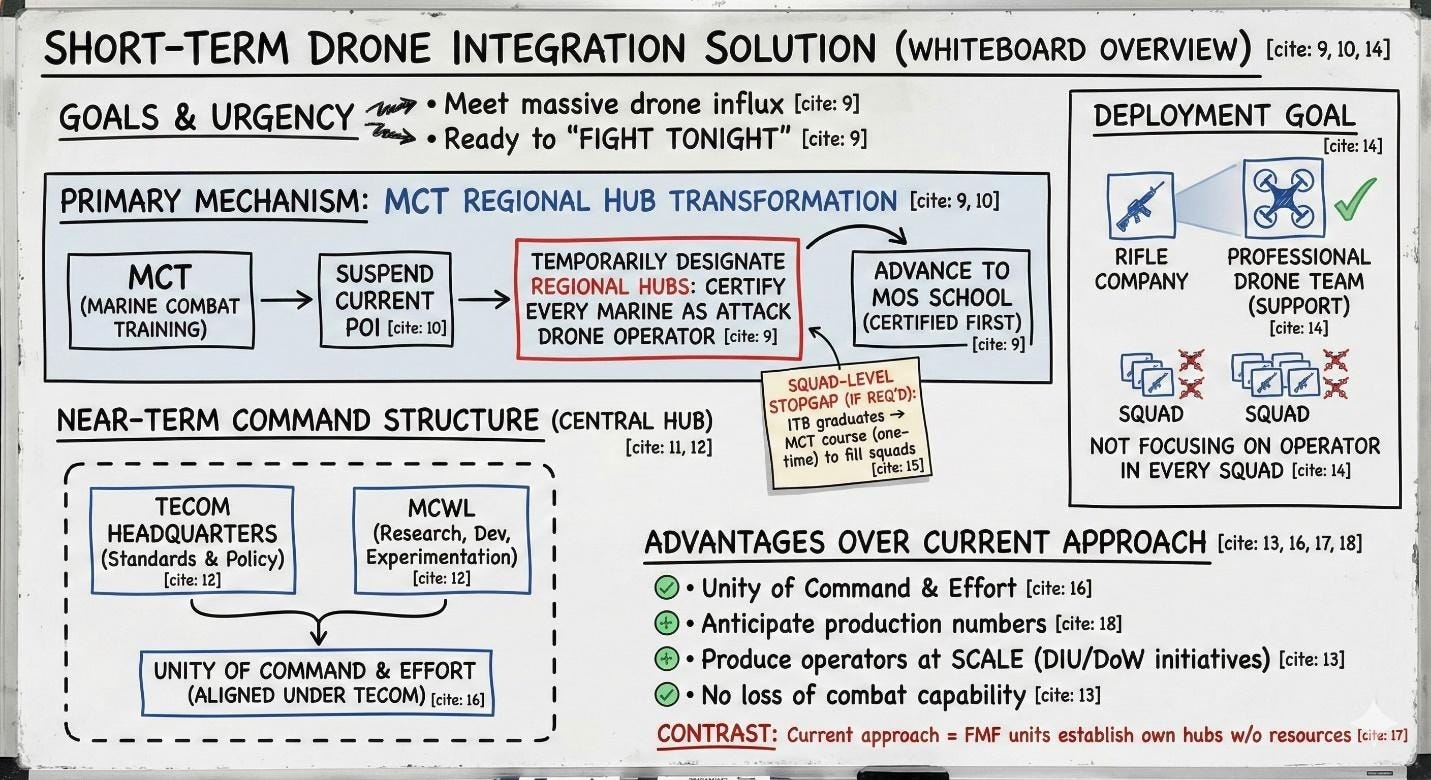

Short-Term and Long-Term Solutions

A short-term solution—necessary to meet the massive influx of inbound drones and to be ready to fight tonight—is to temporarily designate MCT regional hubs where every Marine is certified as an attack drone operator before advancing to their MOS school. MCT should suspend its current POI and execute the proposed attack drone operator course.

In the near term, the central hub should be divided between TECOM Headquarters and MCWL. TECOM PSD would continue to develop standards and policy, while MCWL would advance research, development, and experimentation.

Under this imperfect but pragmatic solution, the Marine Corps would not lose any combat capability by embedding the attack drone operator course within MCT and would position itself to meet DIU/DoW initiatives by producing drone operators at scale. Rather than focusing on placing a drone operator in every squad, we should aim to field a professional drone team in support of every rifle company. If placing a drone operator in every squad is non-negotiable, one company from ITB could send its graduates to the MCT course as a one-time stopgap measure to fill each squad with an operator.

The advantages of this short-term solution include unity of command and unity of effort, with each MSC aligned under TECOM. The current approach instead asks various FMF units to establish their own training hubs without providing any additional resources. An additional benefit of this approach is that it would allow us to anticipate production numbers.

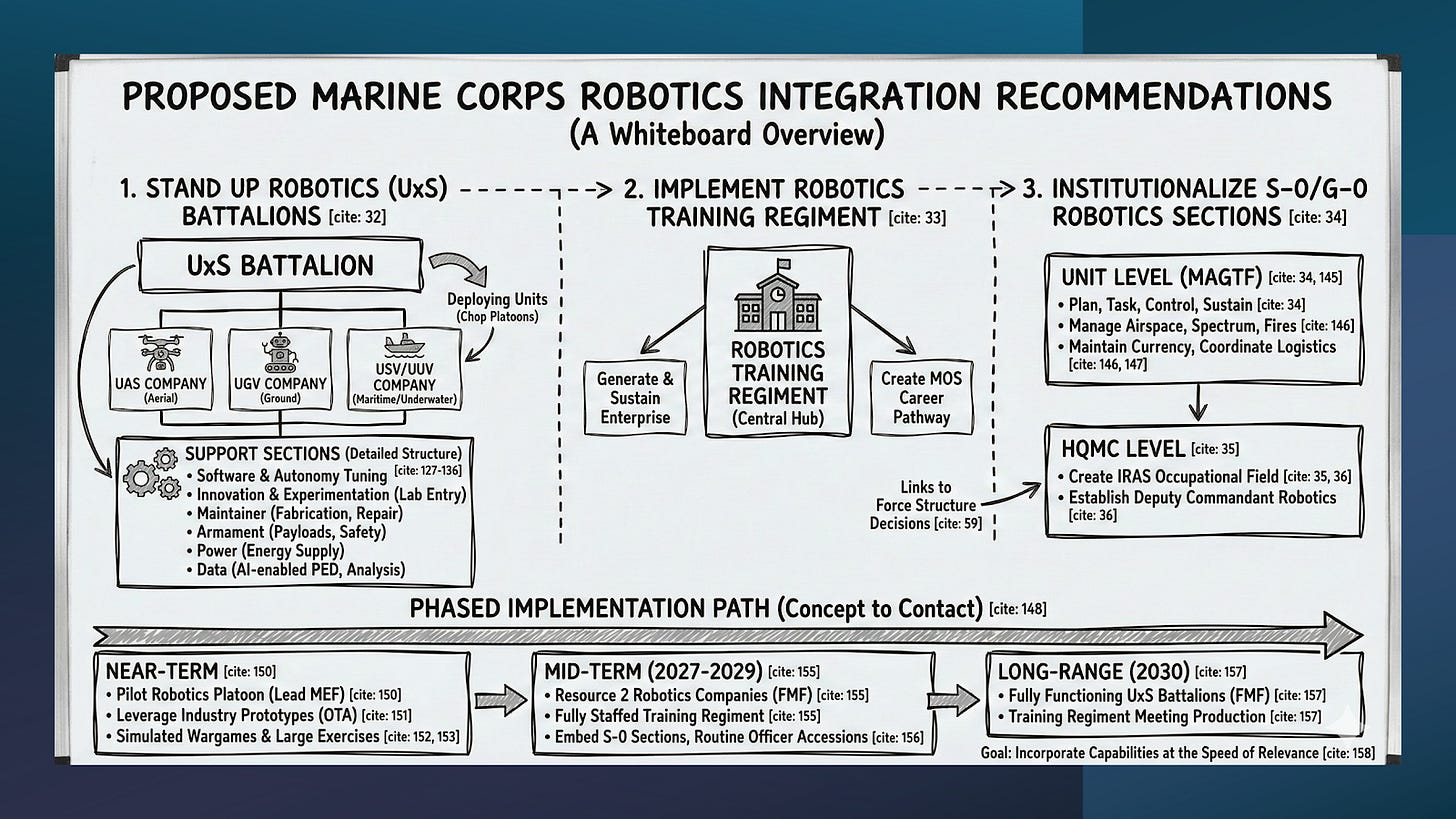

The long-term solution requires the Marine Corps to develop a robotics training regiment where air, ground, and maritime robotic operators are trained to operate uncrewed systems at echelon.

Recommended Current State:

Recommended Future State:

The focus of this essay is not to solve how the Marine Corps must standardize robotics training at a formal learning center and feed these operators into robotic FMF units—things robotics—but rather to make recommendations for the integration of SUAS and the employment of drone teams at the battalion level and below.

Squad Level ISR

The infantry squad does need organic ISR—but it should be a ruggedized, short-range ISR platform, closer to an auto-stabilized, ducted-rotor drone than a racing quadcopter. Think Avata-style survivability: capable of bumping walls, flying indoors, surviving minor impacts, and operated with a tiny, intuitive controller.

The expected performance should be modest:

500 meters of range

Short duration

No payload

Simple controls

Easy to replace

At the squad level, the requirement is simple:

“Look behind that wall.”

“Check the rooftop.”

“Scan that trench line.”

“Confirm what’s upstairs.”

It should be intuitive enough that it does not meaningfully compete with the squad’s cognitive load. It should function like binoculars, not like a weapons system. It should reduce risk, not introduce complexity.

Battalion-Level Employment: Professionalized Drone Teams

Four-man hunter-killer drone teams should be organized within robotics platoons that attach to infantry battalions at D-180. They would operate 3–5 km behind the Forward Line of Troops (FLOT), in positions analogous to our mortars.

This standoff posture allows them to remain supplied with batteries, munitions, and airframes while also enabling basic maintenance. All ISR platforms should be primarily sensors but capable of acting as shooters when necessary. They should be capable of carrying a payload—such as a 40mm or M67-type dropped munition—but for most of their flight hours, their primary function would be to sense, not to strike.

The ISR operator supports the collection plan. The FPV provides an additional capability to the fire support plan.

Future State of Squad-Level FPVs

Until the technology fundamentally changes, the squad-level FPV strike concept is unsound.

Lethal FPVs can be returned to the squad when industry delivers a drone that is as simple to operate and as lightweight as the M72 LAW. Historically, we strapped M72 LAWs to Marines with minimal training, and they were able to employ them effectively.

A drone of this simplicity would:

Operate in denied and degraded environments

Fit in an ammo can

Have 1–2 km of fiber-optic spool

Carry a HEDP-equivalent warhead

Require no RF link

Use a small, simple controller

Squads could then employ these FPVs as pre-assault fires in the same way they employ rockets—but with greater range and accuracy.

Conclusion

The Marine Corps does not suffer from a lack of enthusiasm about drones. It suffers from a lack of structural discipline in how it is integrating them. Drone operators and their systems provide a crucial capability. The Marine Corps should train and develop this capability—and integrate these enablers—the same way it does for every other community. That way, when these drone units attach to deploying battalions, they can effectively support the 0311 lance corporal as he closes with the enemy.

No Bench, No Game: Reconstituting Special Operations Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Depth from the Reserve

Previously printed in the Eunomia Journal and the Small Wars Journal

Lucas Harrell

President Volodymyr Zelensky’s NBC Interview on February 16, 2025, served as a sobering reminder of the human cost inherent in modern warfare. Zelensky estimated 46,000 Ukrainian soldiers have been killed during the three years of war since the Russian invasion in 2022.[i]

That’s substantially more casualties than the U.S. has endured in a long time. For example, according to the U.S. Defense Casualty Analysis System, the U.S. lost an estimated 6,743 service members since 2001 in five different named operations. That’s 6,743 military losses across 24 years as opposed to 46,000 in 3 years.[ii]

That’s a monthly rate for the U.S. (2001-2025) of approximately 24.3 deaths per month versus Ukraine (2022-2025) of approximately 1,243.2 deaths per month. (And this is not counting Russian losses.)

I pause to emphasize that our losses during 24-plus years of war were tragic and felt by every family member and brother- and sister-in-arms across our country and military community. Statistics are cold and unfeeling, but hopefully set the conditions for preparation for what’s next, especially in a global setting that is already experiencing two large-scale conflicts.

The reality is, the U.S. military faces near-peer conflict as its next fight, and a careful analysis has to be conducted on our ability to face losses unseen in the last 40 years of U.S. military-involved conflict. This will require the replacement of, or rather the reconstitution of, U.S. forces, including those who are often first to fight: U.S. military special operations.

In contemporary military strategic discourse, reconstitution—the process of rebuilding combat capability after significant battlefield losses—remains inadequately addressed within the unique operational context of Special Operations Forces (SOF). Specifically, Civil Affairs (CA) and Psychological Operations (PSYOP) forces critical to the modern application of Special Operations and a recognized teammate of the Special Forces that have arguably been over-relied upon for almost every military objective and solution since the beginning of the global war on terror.

Existing U.S. Army doctrine for reconstitution, specifically FM 4-0, Sustainment Operations and FM 3-0, Operations or the process of rebuilding combat capability following significant battlefield attrition is heavily oriented toward conventional forces.[iii] While effective for replenishing standard military units, this approach inadequately addresses the complex training, cultural expertise, and nuanced operational capabilities required by CA and PSYOP forces. The SOF truths, specifically III and IV (Special Operations Forces cannot be mass produced, and Competent Special Operations Forces cannot be created after emergencies occur), specifically highlight this exact fact, yet integration planning ignores its own advice. These units that have been increasingly pivotal to achieving strategic, operational, and tactical military objectives throughout the Global War on Terror and in places not recognized as active war zones, yet full of danger.

For that manpower replacement planning, it’s critical to remember that 92 percent of Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations personnel are in the U.S. Army Reserve, yet that overwhelming percentage of the force is both doctrinally and institutionally hindered from training to the level in which they could be expected to perform in the middle of a near-peer conflict, replacing those who were engaged first with no loss in performance. To argue that the Reserve Component is not expected to perform at the same level and therefore not in need of similar training is to argue that the same aforementioned component is not capable or worthy of such training and protection.

China’s and Russia’s doctrinal emphasis on achieving strategic and operational effects through cyber warfare, information manipulation, and even targeted assassinations amplifies the vulnerabilities of SOF personnel deployed in proximity to direct-action operations. In fact, in such future conflicts, Special Operations Forces (SOF), particularly Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations units, will undoubtedly be targeted aggressively by adversaries employing advanced detection and targeting capabilities unseen in our historical experience. In the next fight (as templated by the modern conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza), we can expect:

Leveraging sophisticated signals intelligence capabilities to detect electronic emissions, track secure and unsecured communications, and exploit vulnerabilities in communication equipment. By intercepting and analyzing digital and radio communications, adversaries can pinpoint SOF units’ locations or operational patterns, enabling precise targeting for missile strikes, drone attacks, or ambushes.

Utilizing extensive surveillance infrastructure combined with AI-driven facial recognition technologies, adversaries could identify SOF personnel through captured imagery from surveillance drones, security cameras, social media exploitation, or reconnaissance satellites. China, in particular, has heavily invested in facial recognition and AI-enabled surveillance, dramatically enhancing its capacity to rapidly track and neutralize high-value targets.

Russia and China maintain robust human intelligence networks capable of infiltrating local populations, allied units, or even logistical chains supporting SOF operations. These HUMINT assets could gather detailed intelligence about unit movements, tactical objectives, or operational plans, facilitating targeted assassinations, ambushes, or sabotage operations. Combined with targeted disinformation campaigns, this method undermines local support and increases operational vulnerability.

Each of these methods presents substantial challenges to SOF survivability. Historical precedent indicates that adversaries will prioritize neutralizing SOF due to their disproportionate operational impact and the strategic disruption that follows their attrition. Are we ready to replace these losses in a timely manner to maintain operational tempo?

In fact, according to a wargame report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the United States would lose 3,200 troops in the first three weeks of combat with China. That number is nearly half of all the American troops that died in two decades of war in Iraq and Afghanistan combined.[iv]

Historical analyses of reconstitution efforts during protracted conflicts, such as those detailed in the recent Military Review article on lessons from the Russia-Ukraine war, underscore the limitations inherent in traditional reconstitution doctrine.[v] Conventional frameworks, which prioritize rapid numerical replacement through accelerated training and equipment replenishment, fail to accommodate the complex demands of the CA and PSYOP community, where so much of the force resides in the Reserve. The detailed expertise required for effective CA and PSYOP operations—ranging from language proficiency and regional specialization to psychological resilience and sophisticated strategic communication capabilities—cannot be hastily replicated.

Moreover, traditional reconstitution approaches do not address the qualitative aspect of SOF regeneration, a concern highlighted in recent NATO analyses examining Russia’s challenges in replenishing its elite forces during ongoing conflicts.[vi] In essence, the current doctrinal framework does not recognize that SOF casualties create capability voids that cannot be quickly resolved merely by numerical replacements.

The readiness gap between Reserve and active-duty SOF personnel, particularly in CA and PSYOP roles, represents a critical vulnerability in the event of protracted conflicts. Addressing this gap requires a paradigm shift from traditional Reserve training models toward a system designed for seamless integration from its current role in conventional support to rapid integration in doctrinally established reconstitution strategy.

Such a discussion, and I emphasize the word discussion, would rigorously evaluate cognitive aptitude, physical performance, and psychological resilience, selectively identifying Reserve personnel suitable for intensive SOF-aligned training pipelines.

For our well-educated, experienced, and capable Reserve Component CA and PSYOP teammates, I will argue that unlike previous senior leaders who argue that we can only do one thing, that in fact, we can both train for and accomplish two things. It’s at least worth discussing, isn’t it?

An article from Breaking Defense discusses how Special Operations Command leadership envisions a “renaissance” for Special Forces amid rising great power competition, emphasizing that Special Operations Forces (SOF) will return to their original, unconventional warfare roots. The SOCOM chief highlights the need for SOF units to adapt quickly to evolving warfare environments characterized by advanced technology, cyber threats, and hybrid warfare tactics posed by adversaries such as China and Russia.[vii]

By elevating Reserve training standards and fostering regular integration exercises with active-duty SOF units, the Army can significantly reduce mobilization latency and enhance operational interoperability. This selective training model, advocated in recent publications addressing Special Operations readiness, ensures that Reserve forces meet the demands of immediate deployment into complex operational environments. Adding a measurement of performance (How well can we replace, if asked, our SOF CA/PSYOP counterparts in modern warfare at our current state of readiness and training) can only push the whole team towards success. Can additional capacity for integration, reconstitution, and downtime minimization not be added into our current conventional doctrinal roles and training? I would argue that modernization demands we must.

Historical precedent and contemporary analysis consistently affirm that the capacity to rapidly replace specialized personnel is integral to sustained operational effectiveness. The development of scalable wartime training pipelines tailored explicitly for SOF roles is thus a strategic necessity.

Such pipelines should maintain rigorous selection and qualification standards while streamlining training timelines to enable expedited deployment without compromising mission effectiveness.

One approach worth debating is establishing a specialized, merit-based selection pipeline within the Reserve CA and PSYOP communities. Such a model could identify reservists with exceptional cognitive aptitude, advanced language skills, cultural agility, and higher physical fitness standards. Would this inadvertently create divisions within the Reserve force, potentially leading to morale issues? Or might it instead foster a positive competitive environment, increasing overall readiness and effectiveness, characteristics of a winning team?

Implementing pre-war identification systems for potential SOF candidates within conventional forces and Reserves can expedite mobilization. Establishing strategically located regional training hubs further reduces logistical bottlenecks and enhances the responsiveness of the training apparatus during the early and middle phases of conflict.

A second approach could involve increasing the frequency and intensity of joint Reserve and active-duty SOF exercises. Embedding reservists directly into ongoing training rotations could dramatically reduce integration friction. While these do occur, is it common enough to build depth?

I can’t help but think of when I completed an Observer Controller and Trainer (OC/T) rotation a few years ago, in which the maneuver commander asked the Civil Affairs element attached to the Rotational Force if they provide a particular type of support to his planned engagement. When the Reserve Civil Affairs team leader started highlighting what he could bring to the table, but stated that they weren’t the SOF Civil Affairs group that were also within the battlespace, the maneuver commander interrupted him with “You’re CA, aren’t you?”

Rarely have I seen a battlespace owner interested in the intricacies of internecine branch conflicts over who is who, and not just expect the same level of results from all parties associated with a job.

This is often the point at which the staunch defenders of the separation between U.S. Army Reserve Civil Affairs and U.S. Army Special Operations Civil Affairs rise up and begin defending U.S. Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command.

They’ll highlight that the Reserve Component CA and PSYOP units and soldiers have a different, unique mission, critical to the conventional forces. That the Reserve soldier brings their civilian career experience, their knowledge of the civilian community, and their wealth of experience that comes from having one of the most arguably utilized military occupational specialties and mission set across the entire world during both peacetime and war as opposed to those active duty soldiers who often aren’t familiar with the civilian environment that they are trained to manage.

I would agree with all of that.

Otherwise, I wouldn’t have spent more than 10 years and 3 deployments within U.S. Army Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command (Airborne) in what I consider the best job in the Army and the highlight of my operational experience, where I have seen the most tangible effects of both inter-agency efforts and non-lethal/center of gravity targeting.

This simply isn’t rehashing that same old conversation.

And it’s certainly not another article from within the CA community asking for a beret, a tab, or anything else that makes our special operations peers sigh and side-eye us.

We have a unique job which makes us special, and it’s okay to like your job.

This conversation is about the reality of war today and preparing to win it tomorrow. We owe that to our peers to realize that asking for self-improvement is not an attempt to degrade or differentiate between our SOF and Reserve Component brethren, but to start to have the discussion on what we can accomplish together. I can’t help but notice during each training iteration with 19th and 20th Special Forces Groups, 4th Reconnaissance Battalion, Naval Special Warfare Group 11, 123rd Special Tactics Squadron, and more, that these sister service Reserve Component special operations groups’ training is modernized and purposeful and they can (and do) integrate quickly into mission planning with their active-duty brethren with no lag.

So, what are we missing?

Special Operations Forces (SOF) are uniquely positioned to be the first units engaged in conflict, particularly in high-stakes, near-peer confrontations where rapid response and strategic initiative are paramount. Given their forward placement and critical roles in shaping operational conditions, these units may also be among the earliest to suffer casualties. Therefore, the ability to swiftly and effectively replace or reconstitute these specialized forces becomes a decisive factor.

Minimizing the wait between frontline losses and the deployment of equally capable replacements ensures that operational momentum is maintained, allowing the U.S. to outpace the adversary’s capacity to adapt. This rapid regeneration of combat power directly supports the fundamental doctrinal principle of unity of effort, enabling commanders to seize and retain the initiative by maintaining continuous pressure at a tempo faster than the enemy can respond.

In tomorrow’s fight, when you enter the battlefield as the second person to do your job, we won’t have time to argue over unit identification codes and special military occupational specialties, but rather who can do their duty. Which is still, and always will be, to win.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not reflect any official policy or position of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, of any other U.S. government agency.

About the Author

Major Lucas Harrell is a U.S. Army Civil Affairs officer, currently serving in the United Kingdom, as the Operations Chief for the Africa Command Counter-Threat Finance Group. MAJ Harrell has completed four military deployments to Afghanistan, East and West Africa, and Eastern Europe. In addition, he has recently completed an operational embassy assignment in West Africa and is currently a student in an Army sponsored master’s program. MAJ Harrell’s writing has been published in the Modern War Institute at West Point, the Civil Affairs Association Journal, Small Wars Journal, and Real Clear Defense. His civilian occupation is within the intelligence community.

The Written Word

Fiction and Nonfiction written by servicemen and veterans.

Let It Rip

Benjamin Van Horrick

“The Big O loved those Rip Its,” said Richie.

“Oliver loved a lot of drinks and food,” retorted Mallory.

His mother had hugged Mallory at the cemetery. “Thank you for watching over my boy in Afghanistan.” Mallory held on for an extra beat.

She and Richie exchanged a glance—Oliver had watched over them.

Richie stared at Oliver's dress blues displayed on a table, absent his Purple Heart and Navy Achievement Medal with V.

Richie and Mallory sat shoulder-to-shoulder at Dagwood’s, racking up a tab while Seger played.

Richie, Mallory, and Oliver came of age in Helmand—driving, A-driving, and the Big O manning the 240 on convoys.

In the ten years since they’d last seen each other, Mallory and Richie had texted each other on the Marine Corps birthday. Now each stared at the row of microbrew taps, realizing their once-familiar trio was now a pair.

“We should get one,” she said. “For Oliver.”

Richie grinned. “Where? We ain’t on Leatherneck anymore.”

“I know a spot—Dollar Tree.”

“Richie, you sure about this?” Mallory shook her head and laughed. “You good to drive?”

“Yeah, sure...”

Richie drove, massive hands engulfing the wheel. Pulling out, Mallory yelled 'CLEAR RIGHT'—muscle memory unchanged.

Inside Dollar Tree, Rip It tall boys sat waiting.

“They make tall boys?' Richie marveled.

“Oh, God. This can’t be real.”

“If we had tall boys, we could have won the war.”

“You want to split one for O?” asked Richie. “Fuck yeah,” responded Mallory.

Richie grasped the dusty can.

Mallory paid, and Richie held the door open as the pair returned to the S-10.

They popped the tab, drank, and shook their heads.

“It was like a roll of nickels in your mouth,” said Richie.

“Why did we do this to ourselves?” said Mallory.

The can clinked against Richie’s spare change as he set it in the cup holder.

Silence filled the cab. Mallory reached over, brushed the tears from Richie’s cheek.Tolstoy’s First Deployment

Eric Strand

I’ll bet that many veterans of the GWOT wondered how on earth they ended up in this remote part of the world. Well, if it’s any reassurance, a young Leo Tolstoy was asking himself the same thing over 170 years ago.

Decades before he wrote his most famous epics like War & Peace, Tolstoy was a young university dropout who racked up significant gambling debts, fancied himself a writer, and left the life of the city and society in 1851 to become an untested artillery cadet deployed to the far reaches of the Russian Empire. He soon found himself stationed in remote forward operating bases and camps in the Caucasus mountains, where the Russian Army had been fighting a low-level conflict for decades against Muslim tribal insurgents in the rugged forest, valleys, and ridges of Chechnya. In many ways, two of his earliest published works, ‘The Raid’ (1853) and ‘The Wood Felling - A Cadet’s Story’ (1855), resemble the writings and memoirs of American veterans of Afghanistan during the Global War on Terror.

In “The Raid,” Cadet Tolstoy describes tagging along with a Russian unit sent to punish a local tribe. He arrives with that familiar cocktail of adrenaline and idealism—the belief that this mission will be dramatic, noble, something to write home about.

Instead, what he finds is hours of waiting, uneasy marching through imposing mountain passes, and the constant sense that the “enemy” is close but invisible. When shots finally crack out of nowhere, the action is chaotic, confusing, and over fast. The officers try to impress each other with bravery and intellect, shouting out lines in French to their educated comrades like ‘Charming... War in such a beautiful country is a real pleasure- especially in good company!’ Yet it is not glory. It’s not a movie. It might as well be a memoir of an NCO’s first patrol in Afghanistan’s Kunar Province in 2006.

In his next piece, “The Wood-Felling,” Tolstoy’s unit is tasked with leading a platoon of artillery to provide overwatch for an infantry company tasked with chopping wood in a hostile valley.

That’s it—he’s eager for glory but bored. In classic Soldiering fashion, one of his soldiers is late to formation before the march starts. There is no sweeping battle—just cutting wood in a valley forest, hoping nobody ambushes them. He watches enlisted soldiers shrug off danger, gripe, joke, and get the work done. In his observations, he ends up classifying the men into 3 distinct types of soldiers that could easily be found in a modern military. I’m sure veterans know them all:

1. The Submissive Soldier: Calm, honest, and resigned to fate—this is the most common type. He comments that a number of these men have limited mental capacity, but exhibit purposeless industry and great zeal.

2. The Domineering Soldier: These are higher-ranking men who are stern, with poetic impulses to duty and courage. They are the preeminent military type that know how to take charge. That said, many of this class are ‘diplomatic’ leaders, meaning they think highly of themselves but aren’t as good as they believe they are.

3 The Reckless Soldier: Impulsive, turbulent, and prone to risk-taking. These men believe in nothing and are drawn to trouble, vice, and other dangers. Often amusing, lucky, and a liability.

‘The War’ drags on—casual and dull. While the infantry is cutting through the forest, Tolstoy’s artillery battery on watch decides to fire on some distant enemy skirmishers for their own amusement. The Cadet chats with his educated Company Commander, who finds the mission dull and wishes he were back in a staff position, when Tartar cannons challenge the Russian artillery battery to a duel—the young officer (very much Tolstoy himself) struggles to hide his nerves and tries to figure out how to look brave as the potshots slowly escalate into a larger skirmish.

It’s a portrait any vet will recognize: the mundane mission that feels pointless, the young leader overthinking everything, the seasoned NCO equivalents who just want to finish the job and get back before chow. Combat, it turns out, is often labor—sweaty, tedious, necessary labor, occasionally punctuated by incoming fire.

And then, like every first deployment, it costs him something. He suffers his first casualty, the humble, experienced, and honest-to-a-fault Soldier that was late for formation who he had spoken to earlier. As the firewood is gathered and the sortie returns to camp, his death haunts the young officer. Back at camp, we see Tolstoy and the men struggle to make sense of it all around the campfires fueled by the chopped wood as darkness sinks in.

These stories remind us that before Tolstoy became a philosopher of war, he was a young officer learning the same lessons many GWOT veterans learned the hard way: war is confusing, courage is quiet, and the truth is rarely heroic—but it’s always human.

The-Wood-felling-Leo-Tolstoy.pdf

Opinion

Op-Eds and general thought pieces meant to spark conversation and introspection.

The Kessler Vulnerability

I. Satellites and Modern Warfare

As the Russia-Ukraine War drags into its fourth/twelfth year, defense establishments the world around continue to reorient towards peer conflict. In doing so, a slew of domains with civil-military overlap must be reconsidered with a sharper military focus. Supply chain integrity, for example, was frankly not of interest to American military planners trying to untangle the tribal politics of the Kandahar Province. Nowadays, the ubiquity of “Made in China” tags on military hardware is cause for ever-growing concern.

Like supply chains, satellites are indispensable to American military operations, but, due to the nature of post-Cold War conflicts through 2022, have developed in a non-kinetic, largely commercial environment. The inauguration of the Space Force in 2019 was a recognition of the coming sea change in warfare, a reallocation of resources proven worthwhile by the Ukrainian experience, which has affirmed the criticality of satellite communications to success on the modern battlefield.

A recent RAND report, Lessons from the War in Ukraine for Space: Challenges and Opportunities for Future Conflicts, extracts key lessons from the Ukraine front. Commercial satellites, in particular the SpaceX Network, which has launched 8,811 of the estimated 12,149 satellites currently in orbit, are observed to have “enhanced Ukraine’s warfighting and reduced the need to field its own capabilities,” although there are “concerns over the reliability of Starlink.” Just what sort of predicament, depending on a single, private satellite provider, a military can find itself in was evident during Ukraine’s late 2022 push into the Kherson region, when Elon Musk shut down connectivity in the contested terrain, hampering the Ukrainian counteroffensive.

Private sector considerations aside, each of the three satellite-dependent “satellite communications (SATCOM), positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT), and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities “have played an unprecedented role” in Ukraine. Countermeasures, naturally, have materialized apace. RAND concludes that “Cyberattacks, Global Positioning System jamming, and other threats have significantly shaped the war, and the growing sophistication of both Russian and Chinese counterspace capabilities only increases the likelihood that the United States and its allies might face similar disruptions in a future conflict.”

In the context of RAND’s report, disruption is a gentle term, implying a temporary and reversible obstruction that slows or hinders operations, and is consistent with the hacking and jamming activities that have defined Russian and Ukrainian counter-space efforts thus far. Disruption is not consistent, however, with a capability only briefly mentioned in the RAND report: anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons.

II. Kessler Syndrome

Anti-satellite weapons have been tested only a few times in history. In 1985, the United States destroyed a defunct satellite with an ASM-135 ASAT missile. In 2007, China hit one of its own satellites orbiting at an altitude of 530 miles. And, in 2021, Russia joined the club of countries to have blown up a satellite in low Earth orbit (LEO). Anti-satellite tests have been relatively taboo.

Each successful ASAT test left a satellite-sized debris field floating in LEO. The second-order effect of such a strike, then, is that satellite debris may impact other satellites, moving through orbit at approximately 17,500 miles per hour. The propensity for a domino effect to occur in which one satellite’s debris destroys other satellites, whose debris affects yet more satellites, was first identified by scientists Donald Kessler and Burton Cour-Palais in their 1978 paper, Collision Frequency of Artificial Satellites: The Creation of a Debris Belt, and is today known colloquially as the Kessler Syndrome.

At the time Kessler and Cour-Palais published their research, there were 3,866 satellites in orbit. Describing the random impact between miscellaneous debris and a satellite, “The average impact velocity of 10 km/s ensures that almost all of the earth-orbiting objects will exhibit hypervelocity impact characteristics when they collide. [...] the shock waves, particle fragments hitting other surfaces, and vapor pressure may cause fragmentation outside the cratered region, possibly resulting in the catastrophic disruption of both objects.” The scientists’ use of the term “disruption” differs notably from RAND’s. The point is that in low orbit, a small, otherwise innocuous piece of debris can destroy a larger satellite.

Kessler concludes—given certain assumptions about how fragments maintain orbits, the relatively unstudied characteristics of impacts between non-homogeneous objects, and anticipated satellite mass—that a debris cloud could create an “average potential flux between 700 and 1200 km” such that “all types of missions into this region would experience a flux level far in excess of the natural meteoroid flux. In fact, since it becomes impractical to protect against impacts larger than about 100 g, all missions would have to expect damage in certain regions of space.” At a time when 3,866 satellites orbited Earth, Kessler’s models indicated that a debris field could affect all satellites in certain parts of the Earth’s orbit. With four times that many satellites and ASAT weapons abounding, Kessler syndrome is no longer a theoretical phenomenon.

In modern peer-on-peer conflict, any country with a suite of ASAT missiles could reasonably exploit the Kessler syndrome to create a debris cloud that damages and likely destroys the preponderance of satellites in low Earth orbit. As militaries come to grips with this eventuality, resources will be dedicated towards developing technologies that might prevent or mitigate the Kessler syndrome, and towards those that might allow military, and indeed civil, communication architectures to persist in the event of a SATCOM blackout.

III. Active Debris Removal

Cleaning up space trash, regardless of its satellite-destroying consequences, is already the subject of significant investment and research. The European Space Agency (ESA), for instance, has approved the Clearspace-1 Mission, in which a Clearspace satellite “will rendezvous with, capture and safely bring down a derelict object for a safe atmospheric reentry - the near future of what space experts call Active Debris Removal (ADR).” The ESA has advanced the Zero Debris Charter, which, as the name implies, seeks to “prevent, mitigate, and remediate” space debris.

Like so many innovations seeping into the consciousness of the world’s militaries, active debris removal is inherently dual-use. The capability to remove satellites or debris from orbit is what Kessler would call a “sink.” Removing satellites from orbit is also enticing from the perspective of those preparing for peer-on-peer warfare. In the most extreme case, one could selectively remove all the competitor’s military satellites, leaving intact both the world’s non-military satellites and one’s own communication architecture, while completely degrading the other’s SATCOM capability. This sort of ASAT strategy is much less crude than forcefully invoking the Kessler Syndrome, but is a technological hurdle beyond simply blowing up a few satellites in LEO and letting physics do the rest of the work.

IV. LORAN and INS

The RAND report notes that, whether ASAT weapons and their corresponding Kessler vulnerability bear out or not, GPS and PNT Jamming are now the status quo within several kilometers of the ‘Zero Line’ between Ukrainian and Russian troops. GPS-guided weaponry is being retrofitted to use alternative guidance systems, such as the TERCOM systems used conventionally by ICBMs or artificial intelligence that can identify targets in-stride. PNT and GPS are critical for much of modern weaponry, and dependence on these systems has been baked in by the experience of facing an enemy—Al-Qaeda and its spinoffs—which could jam neither. Now, it is time for the pendulum to swing in the other direction.

Long Range Navigation (LORAN) receivers achieve positionality by receiving signals from several ground-based beacons that transmit at a low frequency. Following the Second World War, the technology was maintained by the Coast Guard, which used it until 2010. China, which adopted LORAN in the South China Sea in 1984, has maintained the technology. Interestingly, it ought to be possible to develop American LORAN receivers that use the Chinese signals to determine one’s position in the South China Sea (SCS), given an understanding of where the Chinese transmission stations are.

Historically, LORAN was considered an expensive and unwieldy technology. For the ship’s captain trying to launch a missile or torpedo in a GPS- and SATCOM-denied environment, it will be worth every dollar invested in alternative systems. LORAN is proven and can likely be rapidly improved as the technology has idled for decades. Reestablishing it as a capability is a hedge against the Kessler Effect, and a wise investment.

V. Subsea Cables

The natural counterpart to communicating up and over a battlefield is to communicate down and beneath it. Today, there are approximately 750,000 miles of subsea cables crisscrossing the Earth’s ocean floor. It is no news that Russian and Chinese militaries have taken an outsized interest in the thin and fragile fiber-optic connections that move data around the world, and each has developed capabilities to disrupt and destroy cables. The destruction of the Nordstream 2 Pipeline has validated the investment in these investments. And, indeed, severing the cables running offshore of Taiwan would no doubt be part of the opening salvo intended to isolate the island. The current protests in Iran are a stark reminder of the internet’s central place in modern conflict.

In situations where satellite communications are degraded, subsea cables are a partial alternative, provided they can be protected and maintained. Given their relative vulnerability, it is probably wiser to invest in repair and creation capabilities as opposed to attempting to harden fiber-optic cables against the blast, heat, and fragmentation effects they will be targeted with. The lesson here is that individual cables are vulnerable, but a robust network of cables that is not dependent on any one, and which can be easily repaired, will survive on the modern battlefield better than a single, hardened subsea cable. The cables themselves ought to be envisioned as part of a greater communication network, which ought to be able to survive the elimination of any of its respective components, such as satellites, for example.

VI. In Sum

Our dependence as a modern military on satellite communications and GPS, paired with the unyielding physics of the Kessler Syndrome, yields the Kessler Vulnerability. State or non-state actors could use anti-satellite weaponry to trigger a chain reaction, destroying or compromising the majority of the 10,000-odd satellites currently in low Earth orbit and degrading capabilities American forces are accustomed to relying on. Even in circumstances in which satellites are untouched, GPS jamming should be assumed as we move towards peer conflict.

In either eventuality, investments ought to be made in technologies and capabilities that can reduce the propensity and impact of the Kessler Vulnerability. These include active debris removal, LORAN, and subsea cables. None alone will eliminate the risk from ASAT weapons, but in concert, they will be a step toward closing the satellite-sized gap in our communication architecture.

Poetry and Art

Poetry and art from the warfighting community.

Bagram

After Richard Siken

Evan Young Weaver

Remind me of when we forgot the unspoken rule to not talk about

and to forget about those things.

When we spoke to only each other, when others slept, when the diesels humming,

the absence of them is louder now.

It was more as if a baby cried through the night than it was as if

someone woke to comfort, and it stopped.

It stopped but there was another voice and another thump and another thump,

that was not different than our own voices,

not heard against the diesel hums.

Top third of the mountains to the West bright from the rise to the East, telling us,

we are several hours into the fighting season.

Always the fighting season,

always not the fighting season.

We have both forgot.

Traintings

Russell Robinson | www.soggybottomsoyboy.com | @soggybottomsoyboy

16x40", oil on canvas

Email: SoggyBottomSoyBoy@gmail.com

Book Review

The Raider: The Untold Story of a Renegade Marine and the Birth of U.S. Special Forces in World War II

Stephen R. Platt | Published by Alfred A. Knopf | $35.00

Reviewed by Russell Worth Parker

The Raider, Stephen R. Platt’s exceptional biography of Brigadier General (at retirement) Evans Fordyce Carlson, is subtitled as the “Untold Story of the Birth of U.S. Special Forces in World War II,” almost certainly written by the publisher’s editorial and marketing departments rather than the author and esteemed historian, Stephen R. Platt. Speaking from my own experience in publishing, “Special Forces” and “Untold” are words that publishers love, regardless of their accuracy, for their ability to grab a potential reader’s eye. However, there are, on my own shelves, at least nine books detailing the Raider Battalions’ formation, deployment, and combat exploits; their story is hardly “untold”.

What matters, though, is that the Raider story is not what this book is truly about. That is a distinction not meant to diminish the work, but rather to clarify that Platt has produced a comprehensive accounting of Carlson’s life, particularly his experiences in China, offering a far more significant contribution to American and Raider history than yet another blood and guts WWII combat tale (though that exists between the covers of The Raider as well).

The Raider is an important addition to American history, as much as that of the Marine Corps or the Raiders. Platt’s is a thorough examination of Carlson as a man and Marine, with a significant focus on his experiences in China. It’s a complex study of a complex man, something particularly important as we live through an era in which people seek to define one another solely by political affiliations or single events or statements.

Marching with the Chinese 8th Route Army as a military observer impacted Carlson deeply, far beyond the way he would organize and lead the 2nd Raider Battalion in two of the Corps’ most storied combat actions. With a direct line to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Carlson was an advocate for the Chinese communists, whom he saw as espousing democratic principles more enthusiastically than did Chiang Kai-shek and his nationalist army. Carlson was not a communist, a statement Platt offers unequivocally. Carlson was also a clarion for the dangers posed by Japan, perhaps part of why he fought them so passionately once he had the opportunity. But before that, as a man of deep resolve and immutable principles, not least his unwillingness to bend on China policy, Carlson resigned from the Marine Corps. He was, in fact, a reserve officer when World War Two offered him his second and third Navy Crosses.

In combat, Carlson was hell-bent on serving with rather than over his Marines, and the term he inculcated in them, Gung Ho, is one we still use today, though often inaccurately. Platt details the combat on Makin Island, Guadalcanal, and Tarawa through which then Colonel Carlson was unscathed, before being grievously wounded at Saipan while trying to recover a wounded enlisted Marine.

During the 1950s hysteria of Senator Joe McCarthy’s Red Scare, Carlson was tarred with the communist brush, not entirely surprising given his relationship with leading American communists that dated back to the 1930s. In this period, Platt truly illustrates who Carlson was, a man dedicated to his ideals, focused on changes he saw as critical, and demanding of a nation he loved in holding it to account for deficiencies between its professed ideals and its reality.

That Carlson was physically courageous is unquestionable. But Platt does not spare the familial frailties that saw Carlson married three times, the first of which produced a son he saw little of until that son became a Marine himself. For me, it’s a curious aspect of Carlson’s character. He was unwilling to abandon the Chinese, putting himself at a real reputational and financial disadvantage to maintain that fidelity. He risked everything for his Marines. He spoke out forcefully for African-American civil rights well before it was accepted. But he also walked away from two wives and a son, something I feel should have been anathema for a man who lived the creed of the Corps, Semper Fidelis, or “Always Faithful” in so many ways.

Platt’s book is far superior as a history of Carlson’s strategic impacts than any of the other books I’ve read on him or his rival, Merritt Edson. Those books tend to stay at the tactical level, with occasional elevations to the operational, which makes sense. Battalions, regiments, and even divisions are tactical formations, and the people who lead them are tactical leaders. But Carlson forged friendships with Zhu De, an 8th Route Army officer who would later command all Chinese forces in Korea, including those fighting Marines at the Chosin Reservoir. He knew Mao Tse-Tung at least professionally. One cannot help but wonder what could have been had Harry Truman been as interested in Carlson’s thoughts on China as was Roosevelt.

Through his analytical writing, his front-line reporting, his determination, and his ability to forge relationships with a four-term president (and his son, Jimmy, Carlson’s Executive Officer at 2nd Raider Battalion), Carlson transcended his rank and relatively humble beginnings to have genuine strategic impacts on United States policy, something few brigadier generals can say. The Raider details the life that he lived in doing so exceptionally well and offers students of China, geo-politics, military, Marine Corps, and Raider history alike something to enjoy in the process of learning about it.

The Ambition of H.R. McMaster

Jacob Hagstrom

Last month, I exchanged emails with Lieutenant General H.R. McMaster, who may be the most accomplished soldier of his generation. I mention the general in my forthcoming book about Afghanistan, so I thought he might be willing to provide a promotional blurb for the back cover. It is common practice for younger authors to ask established experts for endorsements as a way to attract readers.

I was not surprised when McMaster declined to comment on my book. He is, after all, a busy guy who owes me no favors. But I was surprised by the reason he gave.

In one chapter, I compare McMaster’s views on military strategy with those of his West Point classmate Harry Tunnell:

“The US invasion of Iraq in 2003 was a boon for the careers of ambitious officers such as Tunnell and McMaster. But their paths through Iraq pushed them to opposing views on counter-insurgency.”

In response, McMaster emailed: “I do object to your description of Harry and me as ‘ambitious.’ I thought we were just serving our nation and our fellow Soldiers like you were.”

This reply puzzled me for a couple of reasons. I thought of “ambitious” as a good way to describe competent officers. Army promotions are competitive, and nobody gets to be a Colonel — let alone a Lieutenant General — without a great deal of focused effort. Moreover, if McMaster did not like my description of him, he could have offered no response. He could have said he was swamped at the moment or made up another excuse. Why was ambition such a sensitive subject for him? For answers, I turned to McMaster’s recent memoir, At War with Ourselves: My Tour of Duty in the Trump White House (HarperCollins, 2024).

I had hoped General McMaster would see in me a fellow-traveler: an officer-historian willing to speak truth to power. But it seems the relative value of truth and power has shifted in the general’s estimation following his service as National Security Advisor under Trump.

McMaster’s first book, Dereliction of Duty (HarperCollins, 1997), argued that top military officers in the 1960s had failed to provide President Lyndon B. Johnson with honest advice about the war in Vietnam. Instead, they told Johnson what they thought he wanted to hear. McMaster displayed courage in publishing his book, which was critical of many former officers who continued to hold sway on military policy and promotions.

McMaster was then a Major, already an army celebrity for his tactical prowess in the Gulf War’s Battle of 73rd Easting. He would go on to command the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment in Iraq under General David Petraeus and then serve as anti-corruption czar in Afghanistan. He had joined a rare breed of intellectual soldiers, at home in classrooms as well as on battlefields. Many journalists, familiar with his first book, believed McMaster was the perfect person to offer Trump candid advice, including information the President did not want to hear.

But history does not repeat itself. Though McMaster noted the similarities between LBJ and DJT — both large men whose deep insecurities led them to bullying behavior — the problems for Trump were not the same as those for LBJ (67-8). Whereas Johnson had not heard the truth about conditions in Vietnam, Trump proved impervious to truthful advice. Remember, this was the administration that introduced “alternative facts.”

The book, coming from a once-pro-Trump insider, is a welcome addition to the polarized publishing on the administration. McMaster reveals that not only the nation, but Trump’s team itself was hopelessly divided. There were ideologues, led by Steve Bannon, who encouraged the President’s destructive streak to bring down the “deep state.” Others, such as Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis, sought to protect the President from his unhinged impulses. In the aftermath of January 6, 2021, McMaster admits, the secretaries’ instinct to restrain the President had proven wise. But no one could have predicted that outcome in 2017, he claims.

McMaster sought to serve as an apolitical “honest broker” between the camps, to provide Trump with informed courses of action from which he could choose. The problem was that Trump proved incapable of sticking with any decision. Even when McMaster was able to convince his boss to take an unpopular position, it was often not long before MAGA ideologues persuaded him to change course.

McMaster lasted just over a year in the role, or 41.3 “Scaramuccis,” the unit of measure named for the shortest tenure in Trump’s White House. His antagonists fared little better. Trump fired Tillerson a few days before McMaster, and Mattis retired in frustration when Trump abruptly pulled military assets out of Syria in 2018. McMaster dealt with problems across the globe, from North Korea and China to Afghanistan and Pakistan. But the main foreign policy bugbear during his tenure was Russia.

McMaster took a middle path between the partisans on the left who said that Trump’s campaign team had “colluded” with Russia and those on the right who denied that Russia had interfered with the election. McMaster maintains that Russian hackers did meddle in the 2016 election, but that the intent had been to sow general distrust with the democratic system, rather than to install Donald Trump as President. Trump was averse to all implications that Russia had helped him win; he seemed unable to understand McMaster’s distinction. The issue eventually led Trump to fire McMaster after he joked at a press conference about the prevalence of Russian cyberattacks on the United States.

The author admits he was never able to understand his boss’s weakness when it came to Putin and Russia. Perhaps this insider’s lack of clarity lends more evidence to the theory that Putin has some information on Trump that would compromise even the most shameless man. McMaster, a devout Catholic, does not even dare to speculate about what Putin has Trump on camera doing or saying.

But sometimes the account is gossipy. We learn from At War with Ourselves that Mattis once called McMaster an “unstable asshole” after a meeting about North Korea (224). The author includes this insult as evidence that Mattis and Tillerson refused to collaborate with him. But after my own interaction with H.R., I began to think perhaps Mattis was right. The problem was not that Mattis and Tillerson sought to rein in Trump’s erratic aggression. The problem was that McMaster was eager to enable the President’s militaristic streak. In this case, McMaster was angry that the Defense Department was “slow rolling” his options to the President. Journalist Fred Kaplan has clarified that Mattis sought to prevent his boss from seeing military options that could have had disastrous results.

McMaster’s first book focused on the need for government appointees to give honest advice. His latest book laments that his own advice went unheard. The refrain of At War with Ourselves is: “if only Trump had listened to me.” But if that had been the case, the United States might still be in Afghanistan, and Trump might have started wars against North Korea and Iran, as well. It’s ironic that McMaster criticized Vietnam-era officials for dishonesty that prolonged a wasteful war. McMaster’s purported honesty could have kept the U.S. permanently at war. In short, it is unclear whether armed conflict or diplomacy, collaboration or competition, is best in any given foreign policy situation.

McMaster assumes the shift from collaboration with troubled regimes under Obama to confrontation under Trump was the right move for the United States. In doing so, he reveals his belief that the military should reclaim its role as global policeman. For a career soldier seeking to mask his personal ambition, that worldview may serve an important purpose.

McMaster poses as a centrist, yet he lets slip some embarrassing invective. He referred to Obama’s easing of sanctions on Cuba as evidence of a “New Left interpretation of history at America’s top universities, where students learned that the world is divided into oppressors and oppressed and that geopolitics is a choice between socialist revolution and servitude under ‘capitalist imperialism’” (167). The rhetoric seems more suited to a Fox News anchor than an academic historian. McMaster provides no evidence that ideology forced Obama’s hand in this case. Instead, it is more likely Obama recognized decades-long sanctions had only hurt the Cuban people, with little effect on the Castro regime. Fellow officer-scholar Andrew Bacevich has noted the retort to McMaster on his own “maximum pressure” foreign policy views would be to label him a “madcap militarist,” if one wanted to descend to partisan name-calling.

The book closes with an odd appeal. McMaster hopes that “young people” will read his account and find inspiration to serve public institutions (334). But his book is filled with good reasons not to do as the old soldier chose to do in his final tour of duty. His boss rejected his recommendations, ignored his staff’s careful research, and often subjected him to curse-laden tirades. Fellow executive branch members shunned and belittled him. Only the most dutiful at heart will come away from this memoir with an ambition for a career in politics.

For what it’s worth, McMaster only uses the word “ambition” once in At War With Ourselves, when he discusses the National Security staff’s Christmas party:

“To cap off the evening, I introduced DJ Max Powers and confessed my ambition to be remembered as the funkiest national security advisor” (286).

I can only hope that General McMaster, after washing off the funk from his time hanging around Trump, has been able to get down with his bad self. To me, he will always be the hero of 73rd Easting and Tal Afar. And even without his endorsement, I hope you will read my new book, America’s Favorite Warlord, which will hit bookshelves this Spring.

About the Author

Jacob Hagstrom is a 2009 graduate of the United States Military Academy and a former artillery officer. He holds a PhD in history from Indiana University, Bloomington. He is the author of Asymmetric Warfare (Cambridge University Press, 2025), and his forthcoming book, America’s Favorite Warlord, will be published by Pen and Sword Press in Spring 2026.

——————————

This ends Volume 43, Edition 1, of the Lethal Minds Journal (01FEB2026)

The window is now open for Lethal Minds’ forty-fourth volume, releasing March 01, 2026.

All art and picture submissions are due as PDFs or JPEG files to our email by midnight on 20 FEBRUARY 2026.

All written submissions are due as 12 point font, double spaced, Word documents to our email by midnight on 20 FEBRUARY 2026.

lethalmindsjournal.submissions@gmail.com

Special thanks to the volunteers and team that made this journal possible.