One Retired Marine’s Experience with Active Shooter Training

Lethal Minds Journal Standalone Edition

One Retired Marine’s Experience with Active Shooter Training

Chris Perry

While serving for 21 years in the Marine Corps, from enlisted to officer, as a 0352 and 0302, I sometimes heard that combat arms service members would have a hard time finding a place in the civilian sector where they could apply their skill set. My experience has been that the work ethic and resourcefulness one can develop in the military service are valued and sought after. I initially wrote this for publication in the International Association of Healthcare Security and Safety’s Journal of Healthcare Protection Management. I hope that sharing aspects of this article here in Lethal Minds Journal – aspects of applying problem-solving, decisiveness, and adaptability – will resonate with others who are transitioning after service.

I retired from the Marine Corps in 2006 and was hired as a hospital security director while on terminal leave. In 2011, I became aware of an active shooter training course that law enforcement officers were attending, usually held in schools during summer or winter breaks. This course, the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training (ALERRT) course (www.alerrt.org), is designed to create a common mindset and standard set of tactical formations and methods for responders to active shooter events. Texas State University San Marcos is the site where the curriculum was developed and one of the locations where officers can become instructors. As a hospital security director overseeing a non-sworn department, I had trouble gaining access to this law enforcement-only training until I was able to get my training officer, who was also a reserve police officer, into a class. Once personal contact was made with the instructors, they agreed to teach our security officers in exchange for the hospital hosting the class. In May 2012, we hosted the first course and had a half-dozen security officers complete the 16-hour course alongside nearly 20 law enforcement officers. In all, we hosted nearly 20 classes with roughly 20 students per class. We obtained vital training for our armed security officers, assisted local law enforcement in getting training, and derived benefits from the training being held on a hospital floor plan. We continued developing coordination between hospital security officers and law enforcement officers who are likely to respond to our work sites.

Many readers are probably familiar with the Run, Hide, Fight program, which trains civilians to respond to and survive an active shooter event. As we were developing our program, the Alabama Department of Homeland Security began educating the public on the Run, Hide” program. Some of the same officers who were ALERRT instructors also conducted Run, Hide, Fight training programs in high schools and middle schools in order to prepare teachers to be part of the solution in these challenging situations. Combining ALERRT-trained hospital security officers with hospital clinical staff during a Run, Hide, Fight drill inspired quarterly active shooter drills in a vacant hospital space. It is hard to overstate the value of conducting active shooter training and drills in a hospital setting because law enforcement and security staff can train in hospital-style floor plans, and hospital leadership can develop and exercise immediate action plans.

Our goals were (1) to improve the survivability of hospital staff and patients in active shooter events; (2) to improve the response time and effectiveness of hospital security and law enforcement in stopping the threat; (3) to compress the timeline between injury and victim care in these scenarios; and (4) to validate our Active Shooter written plan, development of security dispatcher scripts, response team go-bags, and medical incident commander checklists.

In Sept 2013, we began to include medical personnel as role players in a med-surg unit, nursing students as patient role players, and security staff and law enforcement as responders. Our hospital education department provided invaluable assistance in developing victim scenarios, setting up the cardiac trainer robots (so staff would have the added difficulty of dealing with that medical emergency), videotaping the drills, serving as observers, and facilitating the clinical debrief. Our training officer played the role of the active shooter, and his use of blank shotgun ammunition to start the scenario ensured that participants moved with a sense of urgency. The drill participants provided useful feedback during drill debriefs and confirmed the value of this realistic training.

Lessons learned from these drills included the following:

-People seldom rise to the occasion; they more often fall back on their training, especially when the adrenaline is flowing. Having rehearsed the plan is vital, whether it is evacuation from an area or sheltering in a safe room. If staff don’t have that “muscle memory,” they will likely freeze or do something else wrong.

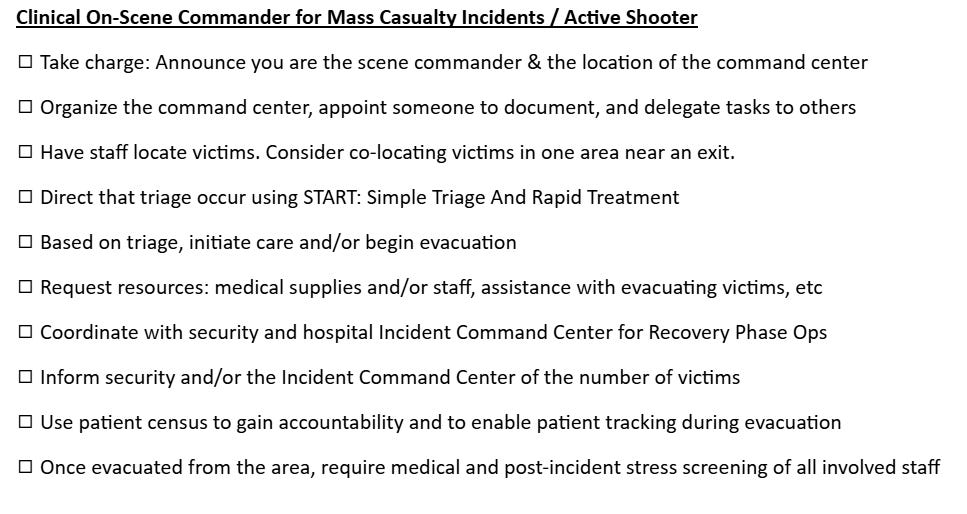

-Most medical staff can rapidly take positive steps in the event of cardiac arrest, but very few hospital staff are current and proficient in dealing with penetrating trauma or in taking charge of a situation that requires triage of trauma victims. We developed a short checklist that the security staff bring to the area and provide to the medical staff member in charge so that the person can more rapidly organize the actions that may lead to preservation of life. Our checklist is provided at the end of this article.

-We continue to develop the idea of a medical response team that could be escorted from the ER by security to the scene of the victims. The question is whether it is more timely and beneficial to have the team go to the victims or have the victims taken to the ER. The answer may be that it is best to be able to do either, depending on the situation.

-Crash carts do not contain supplies specific to penetrating trauma situations, and so we deliberated on how to address that shortfall. Collaboration with our local Fire and Rescue led to their suggestion that we add tourniquets, QuickClot, and pressure dressings to our backpack-style “go bags,” which previously only contained breaching tools, flex cuffs, flashlights, and extra ammunition.

-Law enforcement responders, though they move rapidly to the sound of gunfire, may conduct a very methodical and time-consuming search, either to find the shooter or to look for other threats once the known shooter is down. Based on that factor, we began to create, in our drills, a “warm zone” after the shooter was stopped so that medical response teams could enter the area to triage victims, move victims to a casualty collection point, or evacuate victims to the ER or to another hospital’s ER. The goal is to compress the timeline between injury and care in order to save lives.

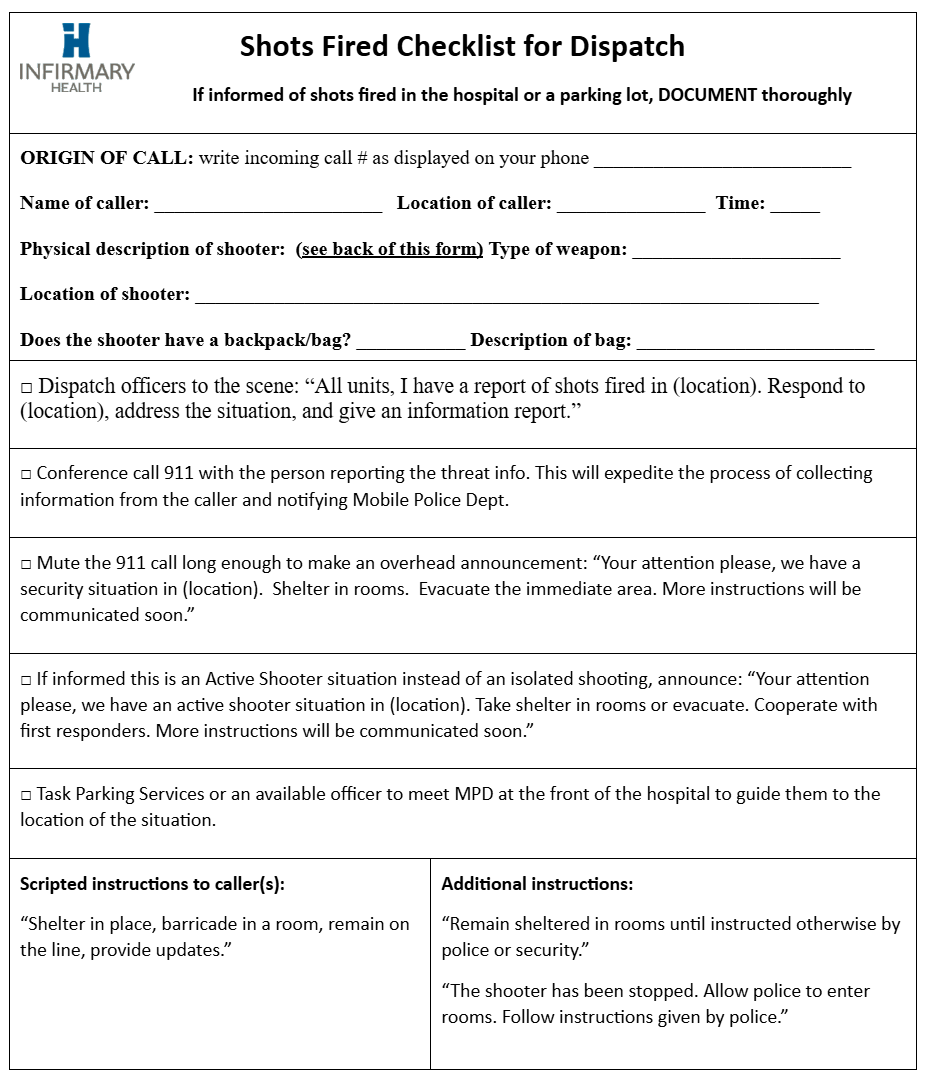

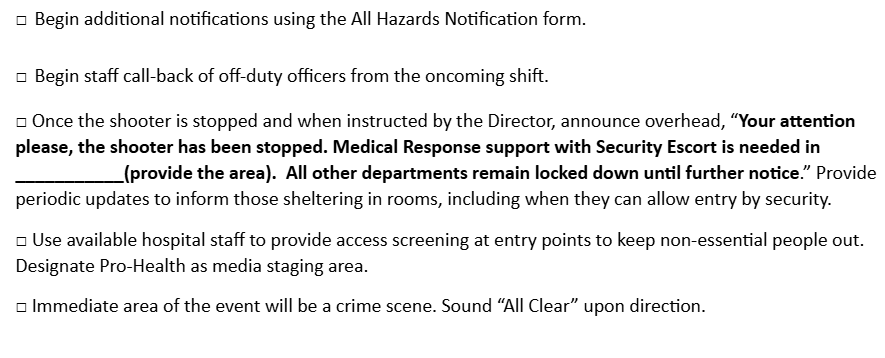

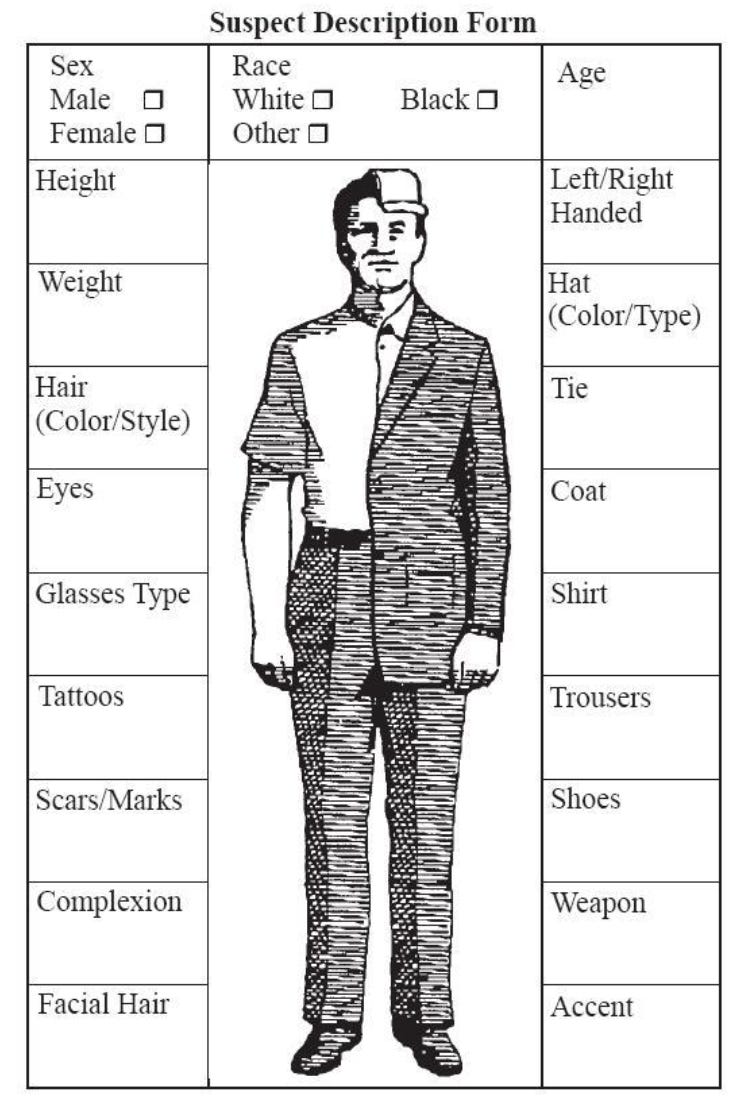

-Hospital dispatchers or telephone operators will quickly get inundated with calls, so it is best if they have a format from which to operate. We revised our template after almost every drill, so dispatchers had scripted messaging to use for calling 911, sending traffic via radio, and making overhead announcements. We also included a physical description template, so dispatchers could use questions to obtain useful information a caller might not think to provide. Our templates are provided at the end of this article.

We conducted many more drills, about one per quarter, with 30 – 40 participants per drill, until February 2016, when we were no longer able to use the vacant hospital. After that, we employed different settings outside normal hours, such as the employee health clinic and the senior center, to continue the training. By having community partners serve as observers for these drills, we were able to brainstorm and develop resiliency and coordination with our local Emergency Management Agency, Department of Public Health, Fire Rescue, and law enforcement. Sustaining, continuing, and improving these learning and training opportunities is our challenge now.

For our business occupancy hospital departments that are not on our main campus, we have been conducting smaller-scale active shooter drills. As a Joint Commission-accredited hospital, we had been conducting disaster drills — usually bomb or tornado drills — at these locations. As non-hospital staff also showed interest in receiving training, we decided to incorporate active shooter scenarios into our drills at our business occupancy locations. Since we had to start somewhere, we began by identifying “safe rooms” and evacuation routes, allowing staff to develop “muscle memory” for their immediate actions. Each business occupancy location is different, with some featuring overhead intercoms, others having multiple rooms with lockable doors, and others offering multiple evacuation routes. The staff gained awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of their particular location and benefited from thinking and walking through the “what ifs.”

One of our business occupancy locations contains hyperbaric chambers for wound treatment. We have conducted two active shooter drills at this location, and our most recent drill included the city’s tactical team. Through the ALERRT training program, we met the tactical team sergeant, who was very interested in having his team respond to and clear a building they had never been in. This scenario was full of challenges, from having numerous patients with mobility issues to having responders unfamiliar with the setting, which created several complex decision-making points for participants. The law enforcement responders gained greater awareness of their external approach route to the building, the challenges posed by the floor plan at this site, and the added complication of having patients in hyperbaric chambers from which rapid egress is not possible. The clinical staff gained a better appreciation of the need for quick response according to a pre-existing plan, since there is virtually no time to devise a plan once the drill starts.

Not enough can be said about the valuable contributions area law enforcement has made to our plans and training. The police department’s precinct commander periodically sends his patrol officers to conduct walk-throughs of the hospital with our security staff to become familiar with the building. The ALERRT instructors spent many hours training hospital security staff and brainstorming possible scenarios we could encounter. Observers from the Sheriff’s Department, US Marshal Service, State Troopers, and area police departments gave informative critiques of our plan and immediate actions. In addition to the numerous benefits of working with area law enforcement, the region in which we are located benefits from a university with a center devoted to disaster preparedness. In Mobile, AL, the University of South Alabama hosted the Advanced Regional Response Training Course in its Center for Disaster Healthcare Preparedness. Various disaster topics were covered during this two-day course, including the topic of active shooters. Part of the session included having students watch the video “Shots Fired in Healthcare,” which is a superb training aid created by the Center for Personal Protection and Safety (which our healthcare system showed during New Employee Orientation). Representatives from hospitals across Alabama attended this course and developed awareness and community resilience through collaboration with their counterparts at other healthcare facilities.

Through these active shooter drills, our healthcare system developed greater resiliency and benefited from collaboration with our community partners. We learned and gained greater awareness that in rapidly developing violent situations, no one can do everything, but everyone can do something.

And that ties in with my initial questions of how a retired infantryman can contribute in the civilian sector. I remembered the various acronyms about planning and communicating plans, from BAMCIS (being planning, arrange recon, make recon, complete the plan, issue the order, supervise) and SMEAC (the format for issuing an order: Situation, Mission, Execution, Admin/Logistics, Communication), and drew on those throughout the process of setting up these training evolutions. Service members sometimes don’t realize all that they have learned by being on a demanding team. By continuing to be adaptable, they can contribute in areas they may not have considered.

The Stand Alone Edition is for long form writing (2000+ words) or video longer than 5 minutes. Submissions are accepted on a rolling basis.

Send your piece to lethalmindsjournal.submissions@gmail.com.

Dedicated to those who serve, those who have served, and those who paid the final price for their country.

——————————

This ends One Retired Marine’s Experience with Active Shooter Training(14JAN2026)

Special thanks to the volunteers and team that made this journal possible.

Strong piece on skill translation that a lot of vets don't see clearly enough. The muscle memory point is critical because most civilian emergency plans assume people will improvise under pressure when reality is the exact opposite. Building that ALERRT partnership through your training officer was smart tradecraft, and the warm zone concept for medical response shows how military TTPs adapt when you actually understand the civilian context not just try to copy-paste doctrine.

Very well said, developed, and on-point. I went through this training at several different companies I worked for, and applaud it. I only did two tours in the Corps as a 2542 in the 80’s, and am now retired, but still remember my PLC, boot camp, and NCO training. I could see this as great training for volunteers in any positions. And as to the author’s point as transferable skills and muscle memory to cite in the transition I throughly agree.