Volume 2

Working on Lethal Minds over the past two months has been an eye opening experience. First and foremost, the level of engagement we have gotten from our community has been astronomical. All our volunteers came out of our reading community, and have been tremendous in getting Vol. II ready for publication. Several of our contributors went through multiple rounds of drafting and re- drafting to make sure their work was as good as it could be for publication. Community engagement and feedback has been constant. Our publication has improved in leaps and bounds in Vol. II, compared to Vol. I.

Some of our sections are a little different this time around. Across The Force is a bit more cerebral, and Health and Fitness is focused more toward mental health than getting your PT score up (You should focus on both; If you’re not fit, you’re gonna die).

Our Journal is growing into something really special. We’ve grown to include a foreign affairs newsletter, releasing July 15, in partnership with several of the best independent journalists and OSINT aggregators around. We’ve opened up a paid model to begin funding Lethal Minds’ growth, though this monthly journal is, and will remain, free of charge to our readership.

We hope our second volume meets the high expectations you have for it, and the standard of work you expect from us.

Be informed, be prepared, be lethal.

Graham (CPT US Army)

Editor of Lethal Minds Journal

The World Today

Across The Force

Opinion

The Written Word

Transition and Career

Dedicated to those who serve, those who have served, and those who paid the final price for their country.

The World Today

In depth analysis and journalism to educate the warfighter on the most important issues around the world today.

The New Front - Northern Provisions

“An ANA soldier walked right up to us, gave me his AK, his helmet with PVS-7s and said ‘See you in America.’ in broken English before walking off.” - US Marine aboard HKIA during the Evacuation of Kabul.

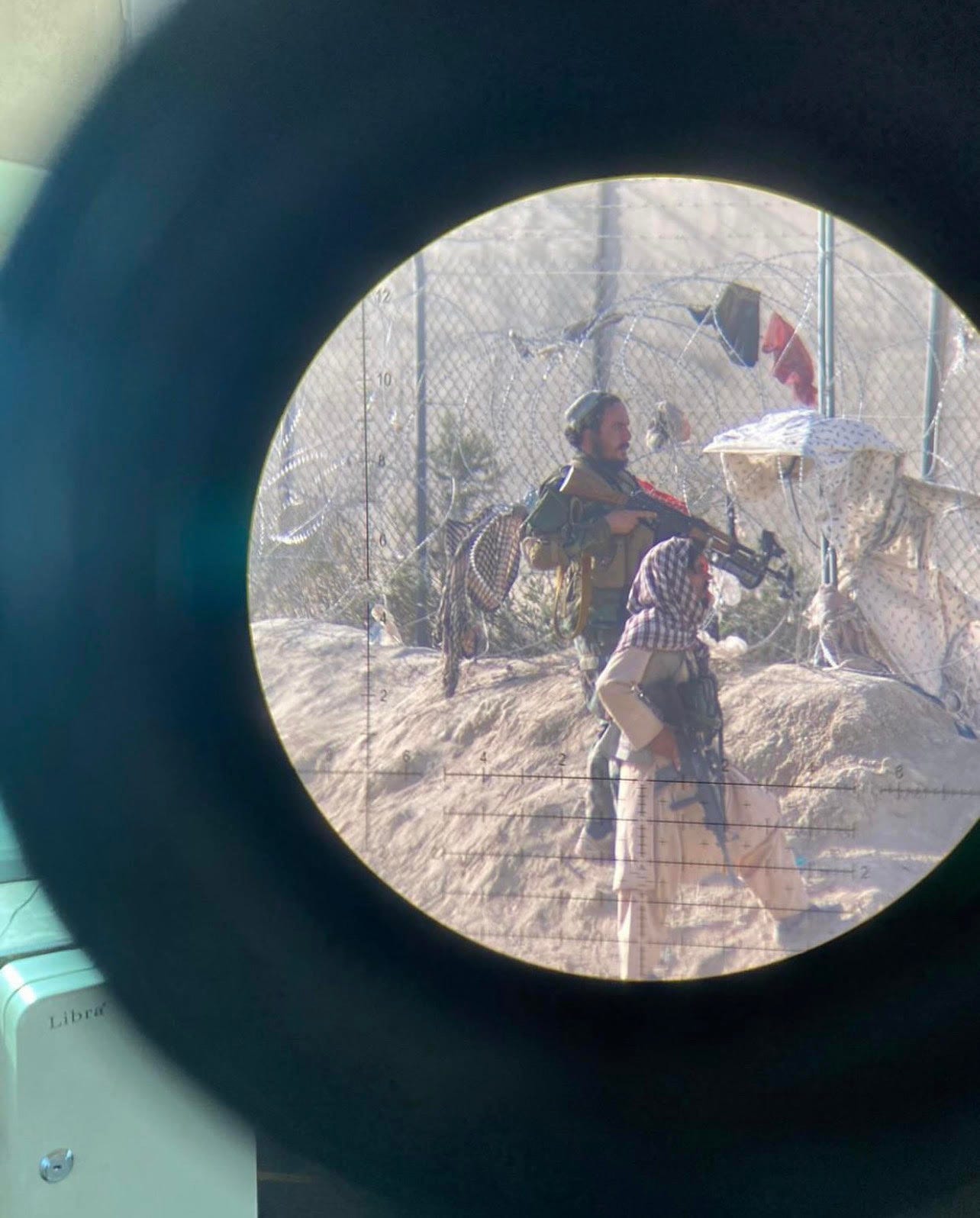

The world watched as the Afghan National Army and Afghan National Police abandoned their posts, dropped their weapons and all but disappeared into the good night, leaving the remaining parts of Afghanistan not held by the Taliban to be absorbed effortlessly. The estimates by the Pentagon and Biden Administration officials were wildly off chart. With the dissolution of the Afghan military came the Taliban acquisition of billions of dollars of weapons, equipment and vehicles. The conclusion of a recent investigation into assets left behind revealed that just over $7 billion worth of military supplies were left behind. This includes but is not limited to 78 aircraft, 40,000 ground vehicles, 42,000 pieces of “specialized equipment” (i.e. night vision, biometric scanners, surveillance gear), 300,000 weapons and 9,500+ air-to-ground munitions. For a fighting force that has operated on minimal terms and with minimal means, and come out victorious, these acquired items serve as a combat multiplier on the battlefield and also give the Taliban the means and capability of legitimizing its military.

As questions were raised and concern grew over the military assets left behind, public officials continued to dismiss them, claiming the vehicles were all demilitarized, rendered inoperable, that whatever was left behind will simply be too difficult for the Taliban to operate and maintain. The painful irony here is that underestimating the capabilities and intellect of our adversaries is what cost us the war to begin with. Yet even in defeat, our pride holds us as a babe to the tit. It has been 9 months since the withdrawal of Afghanistan and as the National Resistance Front has opened up the new front in the Panjshir Valley, video footage, photos and on the ground reports confirm our prior suspicions to be founded in reason. Taliban convoys of technicals, humvees, professional Taliban fighters in plate carriers and half shell helmets. Video footage also revealed the Taliban are utilizing Mi-17 helicopters and other rotary platforms to extract their wounded and dead as well as the insertion of reinforcements.

These aerial platforms were also seen bringing some of their dead to Helmand Province - these images confirm that as of 9 months, the Taliban have maintained (some) of the vehicles left behind and hold the knowledge and experience required to properly operate them. Although unconfirmed, preliminary reports from sources on the ground are also indicating the Taliban have begun using biometric platforms left behind to find prior members of the Afghan military, specifically those of the Afghan Special Operations, who have faced reprisals and summary execution since the Taliban takeover. Images showed Taliban operated helicopters landing on roads in the Panjshir Valley during the skirmishes that have recently arisen - the new front. Despite the recent increase in fighting, this is actually an old front. Fighting between the predominantly Tajik peoples of the Panjshir and the Pashtun Taliban is nothing new. Ethnic tensions and warfare has scarred Afghanistan for decades. It’s only the newly obtained equipment which adds an edge to Taliban fighting abilities.

As the new front opens up, we also see Pakistan conducting airstrikes in Afghanistan in retaliation for Taliban based attacks carried out in Pakistani territory as well as border skirmishes with Iran and consistent bombings and attacks by ISKP (Islamic State Khorasan Province). These are all intriguing developments - painting a broader picture of instability than what many people imagined, leaving the average Afghan stuck between old and new fighting. As of now, the Taliban continue to struggle to bring peace and stability to Afghanistan, failing to certify themselves as a legitimate governing figure capable of unifying Afghanistan and bringing it into a new era. For now the world will watch as old fighting is renewed and the fate of Afghanistan sways in the hands of warlords.

The Implications of Turkey Renewing Military Operations in Syria - S2 FWD

In late May, Turkey's President Erdogan announced renewed attacks in Syria against the terrorist organization the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). “We are taking another step in establishing a 30km security zone along our southern border. We will clean up Tal Rifaat and Manbij of terrorists." Erdogan also said Turkish forces would then proceed, “step by step, into other regions”. Turkish official media outlets said a military incursion into northern Syria was “imminent” and their allies conducted a military parade by its chief Syrian allies, the self-declared Syrian National Army (SNA), a coalition of factions opposing the regime of Syrian Regime President Bashar Al Assad.

“The initial goals are to take control of Tal Rifaat and Manbij, as well as their surrounding areas, to push out the SDF, and allow for residents who had previously been forced out to return.” Abu Ali Atono, a commander in the SNA, told Al Jazeera. President Erdogan said in recent speeches that his government is determined to push back Kurdish fighters who it sees as affiliates to the PKK, which is designated as a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States and the European Union.

These affiliates include the People's Protection Units (YPG), who Turkey deems as the same organization as the PKK. The primary point of contention between the US and Turkey is that the US does not believe that the Kurdish People's Protection Units / Yekîneyên Parastina Gel (YPG) is aligned with the PKK, while Turkey does. The YPG comprises most of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which is closely aligned with the US and coalition conducting operations against ISIS and providing security in northeast Syria.

Turkey and its allies among Syrian forces in the targeted region have launched at least three incursions against Kurdish fighters in Syria since 2016.

The US backed SDF and the Syrian Regime have individually stated to cooperate with each other if Turkey conducts renewed operations in northern Syria to seize Manbij and Tal Rifaat after President Erdogan’s announcement. The SDF has reportedly sent reinforcements to Kobani, which indicates that the SDF perceives that area as another potential area Turkey may attempt to attack. The General Command of the SDF said they are ready to "coordinate with the forces of the Damascus government to thwart any potential Turkish attack and protect Syrian territories." The SDF has previously been considered part of the wider Syrian opposition to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, but has increased cooperation with Damascus in recent years, especially after the spread of Turkish military forces, along with their allies in the Syrian opposition. Turkey and their supported Syrian militias have launched at least three incursions into northern Syria since 2016.

The Syrian president said that Syria would resist any Turkish invasion, saying if there is an invasion, there will be “popular resistance” in the first stage.

“When military conditions allow for direct confrontation, we will do this thing.” Mr. Assad told Russia Today Arabic in an interview.

“Two and a half years ago, a confrontation occurred between the Syrian and Turkish [armies], and the Syrian army was able to destroy some Turkish targets that entered Syrian territory. The situation will be the same according to what the military capabilities allow. In addition, there will be popular resistance.” President Assad said. This popular resistance will primarily consist of the Syrian Regime and the SDF; however, it is likely that Iranian backed militias currently operating within Syria will resist the SNA and Turkey but will primarily consist of protecting Shia dominated ethnic populations.

Sergey Lavrov, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Russia, said after meeting Mevlut Cavusoglu, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Turkey, "We understand fully the concerns of our friends over the threats created on their borders by outside forces that are fueling separatist sentiment." ‘Outside forces’ most likely refers to the US and the other members of NATO. Lavrov’s statement regarding ‘threats created on their borders’ is in line with the rhetoric used to justify the invasion of Ukraine.

US State Department officials have condemned any renewed attacks.

"We are deeply concerned about reports and discussions of potential increased military activity in northern Syria and, in particular, its impact on the civilian population." US State Department spokesman Ned Price told reporters.

"We condemn any escalation. We support maintenance of the current cease-fire lines." "We expect Turkey to live up to the October 2019 joint statement, including to halt offensive operations in northeast Syria." Price said. "We recognize Turkey's legitimate security concerns on Turkey's southern border. But any new offensive would further undermine regional stability and put at risk US forces in the coalition's campaign against ISIS." Price said.

This will put the US in a unique situation if Turkey renews attacks on Syria, where the US-backed SDF/YPG will cooperate with the Syrian Regime and possibly indirectly Russia to repel an assault from Turkey, a NATO ally. This situation could put US troops in danger from SDF/YPG members who think that the US isn't doing enough to stop Turkey, which could erode the US-SDF relationship in providing security in northeast Syria and counter terrorism operations. It is likely that the SDF may leverage their cooperation with the Syrian Regime to reach a diplomatic agreement for semi-autonomy in northeast Syria like the Kurdistan Regional Government in northern Iraq.

While Russia walks a fine line between understanding Turkey’s stance on the assault and officially endorsing renewed attacks, Russia will most likely support the Syrian Regime in providing intelligence and operational guidance against Turkey. Russia will also attempt to sow division between Turkey and the rest of NATO, especially regarding the PKK – this will most likely be seen during Sweden and Finland’s attempts to join NATO.

Alternatively, growing relationship with the Syrian Regime could potentially cause the SDF and Russia to be more diplomatically engaged, which could increase Russia’s influence within the YPG and SDF. Russia has been the Syrian Regime’s ally dating back towards the days of the Soviet Union, and this long-standing ally with the official government could result in more diplomatic victories for Syrian President Bashar al Assad with the leaders of the SDF, such as ceding SDF held territory holding oil refineries for example.1

The Man Who Wears Three Hats - Cory Bravo

Throughout the preceding weeks, multiple news outlets stated China’s zero-Covid response and economic issues can be reversed if Xi Jinping 习近平 were to step down as President of China. However, one key aspect that most, if not all, of these entities miss or do not take into consideration is that Xi actually holds three positions, only one of which is president. The other two positions — General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) — are substantially more powerful than the President of China.

The General Secretary and Chairman of the CMC are more powerful than the position of president because they represent the two most powerful entities in China— the Chinese Communist Party and the People’s Liberation Army. Within China, there exists two hierarchical power structures, provincial/local governmental entities and a separate structure for the CCP. Normally there exists two positions, a governmental position and a party position, with the party position normally being more powerful for two reasons. The first reason is that the bureaucratic positions will often also be the deputy or other lower CCP position. The second is how the CCP will often use the bureaucratic positions as a scapegoat under most circumstances. An example of this dynamic is how the Mayor of Shanghai (Gong Zheng 龚正) is subordinate to the Party Committee Secretary of Shanghai (Li Qiang 李强) because of party dynamics. Li is in a more powerful position compared to Gong by virtue of Gong also being Deputy Party Committee Secretary of Shanghai. Further, Li is also in the more powerful position due to him also being a part of the CPC Political Bureau (Politburo).

It should be noted not every administration level within China rates two separate positions. While there are usually two positions of power at every level of government, the village-level is significantly different from other administration levels, to include the second lowest level of township. It is not out of the norm for a person to occupy both positions at lower levels such as village level. This is due to the town not requiring two separate positions or the party organs at the higher level thinking it would be too cumbersome. However, under most circumstances, there will be separate party and village entities – called party branch and village committee – at the village level. This dynamic enables the CCP to extend party control even to the smallest villages within China from the northern reaches of Northeastern China 东北 to the various ethnic minority villages in Yunan province.

Going further, Xi shielded Li — one of his allies — and continued to do so during the Shanghai lockdown by placing the blame on the regular government positions and to a lesser extent lower level party officials. The reason why Xi is actively shielding Li is due to the high probability Li will be promoted to the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) during the 20th Party Congress in November. However, the initial handling of Shanghai’s response to the city’s COVID-19 outbreak could diminish Li’s chances of becoming a member of the PSC. Li Keqiang’s 李克强handling of an HIV outbreak when he was the governor of Henan province is an example of how a disease can derail a high ranking party member’s career. In the late 1990s, there was a massive outbreak of HIV in Henan province that led to thousands of individuals – from farmers to children – contracting HIV from government led rural blood banks. The individuals contracted HIV through the contaminated blood and plasma from the rural blood banks that did not screen the blood for HIV. In turn, massive amounts of criticism were leveled at Li Keqiang in response to his muzzling of the media and crackdowns on the resulting protests.

The consequences of Li Keqiang’s mishandling of the HIV outbreak were catastrophic. Before the outbreak, Li Keqiang was considered to be in running to be the next President of China instead of Xi. Furthermore, the roles were supposed to be reversed, with Li Keqiang being the President of China, General Secretary, and Chairman of the CMC with Xi taking up the position of Premier. Due to the scandal, Li Keqiang was deemed ‘tarnished’ by the then President of China and Xi’s predecessor, Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 and the rest of the CCP top leadership. Xi was picked ultimately because he represented a compromise candidate and a strong second pick in lieu of Li Keqiang.

The PLA occupies an unique position in China by virtue of it being a ‘party army’ and thus a political entity just as much as a warfighting organization. The PLA is in many ways, the ultimate guarantor of the CCP’s continued hold on power. While there is a defense minister (Wei Fenghe 魏凤和), the PLA is subordinate to Xi and the CMC by virtue of being a political entity. Wei's position does not have any power in the same sense as the Secretary of Defense, and in fact they are different in several aspects. Most people believe Wei’s position and role is analogous to Defense Secretary Austin’s (USA) or Defense Minister Henare (NZ). One of the most important – and noticeable – differences is how Wei is an active-duty PLA officer. This is in contrast to almost all of his western counterparts who are either civilian or retired military officers. The reason why the Defense Minister is a PLA officer instead of a civilian party member lies in the CCP’s desire to maintain control over the PLA.

Another difference is how the Defense Minister has no command authority, as can be found in their western counterparts. The formal command authority for the CMC is best understood by looking at the 2014 implementation of the “CMC chairman responsibility system” 军委主席负责制. The implementation of the system led to several key features involving the consolidation of the command authority under the chairman of the CMC. Specifically, the system explains how all significant issues of national defense and army building are decided by the chairman. The second key feature is how the chairman (Xi) will provide unified leadership and efficient command once the decision is made.

Finally, it should be noted that Wei occupies a relatively minor position as a member of the CMC. Wei – along with three other active duty PLA officers – are members of the CMC while Xu Qiliang (许其亮) and Zhang Youxia (张友侠) are Vice Chairman of the CMC. This hierarchy effectively places Wei at the lowest position within the CMC.

Xi sitting down as President of China would change nothing since he would also still occupy both the Secretary General of the CCP and the Chairman of the CMC. Furthermore, Xi would continue to exert control by holding two positions since they are the true positions of power within China, whereas the position of president holds no authority. This dynamic extends to all levels of bureaucratic administration within China, with the CCP party positions holding more power than their bureaucratic counterparts. This enables the CCP to essentially weather any criticism or fallout from any crisis by shifting blame to their bureaucratic counterparts.2

Across the Force

Written work on the profession of arms. Lessons learned, conversations on doctrine, and mission analysis from all ranks.

Ordinary Men Review - Voodoo Pen And Paper

Christopher Browning's Ordinary Men underscores the notion that thousands of Jewish people were not killed by fanatical card-carrying SS members during the Holocaust in Poland. Rather, many were ordinary men who savaged Polish towns and were responsible for the violent murder of thousands of innocent men, women, and children in 1942. Browning unearthed several German court documents and produced a tragic history that follows the "Ordinary Men" of Reserve Police Battalion 101 during the Final Solution in Poland. In Ordinary Men, Browning claims that "Explaining is not excusing; understanding is not forgiving." He argues that a multi-causal explanation of motivation combined with situational factors and ideological overlap allowed the men to dehumanize their victims and turn ordinary men into willing executioners.

Browning provides a brief backstory on the battalion before 1941. However, most of his work focuses on the events following a reformation and establishment of the reserve battalion from May 1941 to June 1942. The years that followed the reformation closed with thousands of dead European Jews at the hands of RPB 101. Even in modern times, reserve units do not always represent the typical soldier serving on active duty. Many have civilian jobs or perhaps even prior active-duty service. Men of the Reserve Police Battalion were no different. Of the non-rates, roughly 63 percent of them had a working-class background, with 35 percent being lower-middle-class and having an average age of 39. (47) Many soldiers were from Hamburg and often too old for military service outside of war standards. Only a few displayed representations of the SS or Nazi party. Concerning "age, geographical origin, and social background, the men of Reserve Police Battalion 101 were least likely to be considered apt material out of which to mold future mass killers." (164)

When the men arrived in Poland for their first significant Jewish eradication assignment, the Battalion Commander addressed his men and briefed them on the upcoming mission. After explaining their "unpleasant" task, with tears in his eyes, the Major asked those who could not partake in the mission to step out. With the limited number of soldiers who were willing to step out, it was apparent that the soldiers of the 101st felt it was their duty and obligation to their nation to complete the task. Furthermore, their task was directed by a legitimate governing authority that wished to see that these eradication orders were carried out in such a cruel and unusual way, even during wartime.

A common trend occurred throughout the book amongst the senior leadership. During these vicious attacks, it appeared that on several occasions, officers chose to give the orders but blamed them on higher authority and even avoided the killing grounds in attempts to escape their reality. There are two major points the author should have addressed in more detail when further explaining the rationalization or motivation for how these orders were carried out. First, placing the blame on higher authority allows them to justify giving distasteful orders to subordinates and the feeling that they are absolved from responsibility. Furthermore, the trigger pullers receiving the orders must seek to remove themselves as an individual, so the unit operates collectively. Therefore, when there is a gap between the issuing authority, and once individualism is removed, a collective unit executes the orders directed by a higher, absent, and legitimate authority creating a slippery slope. To reiterate this effect, "war is the most conducive environment in which governments can adopt "atrocity by policy" and encounter few difficulties implementing this." (162)

Browning claims that no indoctrination or established prerequisite training plan led these soldiers to kill. Instead, it was career progression, the threat of isolation, or becoming known as a "non-shooter," a weakling, or non-conformist among the collective whole. Some of Browning's critics believe the will to kill existed in most shooters before the Final Solution due to ideologies or preconceived thoughts of hatred. However, it seems plausible to believe that most men may have been unwillingly implicit conformers. Moreover, for many who committed these acts, justification was needed to put their personal beliefs aside for their country. Whatever their motivation was, evidence showed that over time, soldiers from RPB 101 adopted a standard operating procedure that devastated the lives of many. Browning revealed what ordinary men could become under poor leadership and a governing authority that orders and approves of such atrocities against humanity. As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold and their mistreatment of civilians, this book’s relevance today remains uncontested. Ordinary Men Should be read by anyone serving in the armed forces or who has an interest in Holocaust or WWII history.

On Leadership - Nate Gladdin

“Again the men spoke of [General Washington’s] composure in a critical moment, and the infantry rallied to his quiet leadership.”

David Hackett Fischer masterfully captures the composure, humility, tenacity and resilience needed by our first ever Commander-in-Chief in his book Washington’s Crossing. At a time when our military, as well as our nation were still attempting to figure out who we were, Washington stepped into what must have seemed an impossible task. The more I read about our first ever Armed Forces commander, the more I notice it wasn’t his tactical or strategic leadership which carried us forward. It was his heartfelt sense of duty to his soldiers, as well as a willingness to adjust after failing. He was the leader we, as a nation, needed to begin this phenomenon known as democracy in our fertile land.

At times he wept, quietly, but wept nevertheless because he knew the duty he was given to lead men meant he had to own their deaths in battle. Journal entries of even the lowest of ranks speak of his resolute leadership. Few of the examples I find from them speak to the technical side of him as a leader. Their focus is on how he moved amongst his men, how he inspired them, how he led them.

Leadership is an art form which can never be perfected. However it can constantly be improved upon in a way that truly helps others. It takes intention and attention. It requires you to check your ego while still displaying a certain fortitude which others can feel confident in. Leaders must display compassion while still holding themselves and their people accountable to the task at hand. They should demand to be held responsible at all times while still giving ownership to those they lead and serve. It is both exhausting and rewarding. Good leaders, real leaders, have character which endures and forever improves those they are charged with leading.

As followers we all seem to understand rather quickly when we have leaders who we know are dedicated to both us and the mission. When you are the leader though, you may strive for long, lonely stretches of time without truly knowing if you are moving in the proper direction. Sometimes all you can do is focus on being a just person who is dedicated to your subordinates, and support them in a way that allows them to develop and complete the mission.

Leadership should not, however, feel lonely. If you surround yourself with technically competent Soldiers, Sailors, Marines or Airmen who are allowed to communicate with you honestly, then you will have ample thought and support when decision making is required.

Writing this has not been easy. I have spent much time in reflection on past leaders—some exceptional, some adequate and some subpar. I’ve assessed myself and wondered if I have done enough in times I was called upon to lead. Many times I have failed. However, I have always looked to my mentors for advice on how to improve and evolve. Turning to them wasn’t always easy because it meant admitting defeat, yet every time I could temper myself and wisely ask for feedback, even when it pained me to do so, I found I received more than I could have ever hoped for. My mentors have truly been exceptional in my development as a leader. It is because of them I even feel worthy of writing about this topic. In observing them I’ve settled on five traits evident across the board. Humility, integrity, empathy, composure and decisiveness.

Those leaders who I aspire to learn from are good people. Some of them were better tacticians than others. Some understood the long-term strategy required to build an organization, while others were incredible leaders of Airmen while carrying out the mission downrange. No matter the scenario all of them were trustworthy. They cared more about the quality of human being in the uniform than the uniform itself. They listened, then led.

Great leaders bring out greatness in others. They purposely evolve as time goes on, looking to learn new ways to serve those they are responsible for. Take note of the word serve. If you are to reflect on any good leaders you have had the pleasure of following, whether it be a youth coach, community leader, commissioned officer or your first ever enlisted supervisor, you could most likely point to the various ways in which they helped you progress. They were no doubt choosing to provide you with a pathway to success based on their own personal experiences. They were serving their subordinates through guidance.

Leaders worth following look to accomplish their assigned mission but never at the expense of a subordinate. Servant leaders foster growth in those they are responsible for. They approach their role with intent to serve others along the way and realize if those junior to themselves are not growing and improving then they have fallen short in their duties. They provide for others before they provide for themselves, yet they understand the importance of self-care.

Beware of the person in charge whose method of leadership does not involve proper explanation along with guided assistance when you ask for it. Those who chose not to learn from others, rising through the ranks depending solely on their own achievements, may or may not be malicious but they will more than likely lack the skills needed to develop others. I search for leadership mentors who had leadership mentors.

Leaders are not born—they are developed. Some who are given the responsibility do come by it more naturally than others. However, I wouldn’t hesitate to state they are constantly working to evolve, which helps in all aspects of their life.

Not every great leader has to be overly vocal, but every great leader must be able to communicate. Those who can express their intent effectively will notice those who follow them may also begin to look towards them as true mentors. Leaders should not shy away from this honor.

Without exception or excuse, those who wish to lead must be willing to stand up to those in positions of authority if ethical boundaries are crossed. Not only will those who are required to follow their leaders be watching you, they will also build their tolerance and expectations from your actions when tough moments arise.

Practice empathy and carry yourself humbly but never show less strength than needed. The best leaders I have ever had the privilege of working for were always approachable, capable of listening and willing to invest their time in others. However, I never doubted their ability to discipline me if I let down the team. More often than not I would accomplish my duties not only because it was the right thing to do but because I knew they would be disappointed in me otherwise. I never questioned my punishment with these individuals because I always knew they were handing it out after I earned it. Those who wish to lead must not hesitate to reach out for guidance. They should also be willing to check their ego and learn from peers and subordinates alike. Those who are always striving to develop, no matter where the lessons come from, will do just that.

Understanding and managing your own stress is imperative if you want to be an effective leader. While you cannot always control your surroundings due to the fact that life is ever changing, you are solely responsible for how you respond. Effective leaders learn to detach their emotions—not lack them altogether—from circumstances. Choose to make decisions with a clear mind. I suggest looking to the Stoics for practical ways to apply this to your arsenal of leadership. Remember it is your responsibility to prepare your replacement. This means it is your duty, no matter your rank, to prepare the next generations of leaders.

As an example, shortly after arriving at my first flying unit after graduating from flight engineer school, I flew with one of the most experienced evaluators in our Operations Group. He also happened to be my element flight chief. I was incredibly nervous to fly with him because I didn’t want to mess up and have him correct me. This was insecurity and ego.

Over the period of a four day training trip I made countless mistakes and struggled to coordinate things in a fluid manner with my fellow aircrew members. I was convinced he would downgrade me on my training folder and suggest remedial training. When we returned to home station and sat down for our formal debrief, he asked me what I had “done well” while we were training. This caught me off-guard. I told him nothing, and he countered with a list that filled half a page. My mentality shifted, and I was eager for his feedback. I remember him saying, “My job is to make you better. I’m here to make sure you don’t do anything that will get you or your crew hurt or in trouble. But if I don’t allow you to make mistakes, I can’t help you improve.” He then gave me advice that I have now carried forward with me for well over a decade. He told me that being a good leader isn’t always about preventing others from making mistakes, it is about teaching them how to recover and correct them. This SNCO was truly an effective leader and many times I have reflected on this leadership lesson. I am better for knowing him.

You can look to your mentors, learning from their successes and failures. You can attend seminars and in-depth courses on the subject. Many in positions of leadership do. If at all possible, volunteer to attend sister service schools and also volunteer for deployments in a joint environment. I have mentioned it in other writings, but I feel it is worth repeating here. Each branch brings its own perspective and methods for developing their members. It can only broaden your knowledge of what is required by others, as well as increase your leadership aptitude.

Training environments, including daily squadron duties and exercises, are great ways to improve your approach to the art of leading. While training may not be real world from a mission perspective, it does offer you plenty of actual decision making, problem solving and team building scenarios. Because of this, strive to take these opportunities as seriously as possible.

I would like to finish with one final observation. One of the more encouraging aspects of learning to lead is you can study great leaders who came before you. Through extensive reading one can look at leadership from any angle desirable. There are countless books on tactical leadership, operational leadership and strategic leadership. You can find ones covering servant leadership, team-oriented leadership, and practical leadership techniques for turning around a subpar squadron. Even more beneficial is how many examples great leaders will give on how they failed and learned from their mistakes. Building a yearly reading list will not fail you in your pursuit to become a well-rounded leader. A list of books I find useful are listed below. If you are reading this, please do not hesitate to inquire for other suggestions.

Book Recommendations

1. Shackleton’s Way, Margot Morrell and Stephanie Capparell

2. Washington’s Crossing, David Hackett Fischer

3. The Hill, Aaron Kirk

4. Turn the Ship Around, L David Marquet

5. Grant & Lee, JFC Fuller

Playing to the Tactical Edge: The Need to Bridge Ideas into Strategic Effects - Matthew M. Miranda

Modern militaries are plagued by a primitive mindset. For hundreds of years, mankind has developed ways and means to destroy civilizations and seek dominance across societies, regions, and the globe. As the professional army evolved, the center of world power has continued to move West. From the Ming dynasty in China to Alexander the Great and the Macedonians, then on to Rome and beyond, global hegemony has rarely moved Eastward. The foundation for this phenomenon can be found through geography, technology, plagues, and other extensive theories which have been thoroughly vetted by a number of historians. Where the West stands apart from the Rest, however, has been the ever-evolving culture of inclusion of ideas – across all aspects of society – which has sparked everything from the rise of the nation states, to the introduction of new domains of warfare. As the American military continues the evolution of military science and adoption of advanced concepts seemingly lightyears ahead of the majority of the world, our institution fails to identify that our most valuable asset, our innovative warfighters, are slowly left without a capacity to influence or contribute to the ways in which they themselves wage modern war. From decentralized decision-making capabilities in the field to critical Department level decisions in the Pentagon, American military leaders at all levels are not equipped with the mindset to contribute ideas, which ultimately inhibits maximum strategic effect in the next generation of warfare.

American military leaders have been thrust into an era of strategic competition, and the strategic perspective of the United States has changed course dramatically since the publication of the 2018 National Defense Strategy. With the rise of China and Russia and other adversaries in the East, the United States is postured to employ whatever means necessary to assert our power. This is not just limited to military strength. Politically and economically, the focus of the United States has all shifted Eastward, in an attempt to understand and thwart pervasive autocratic ideologies which have historically ravaged the world. The United States military in particular has reached a point where operations plans directly seek to neutralize Chinese and Russian threats in the battlespace, yet there are doubts American capabilities will outpace those of our Eastern competitors, or even worse, match up in a high-end fight as it stands today.

There is hope. Over the course of human history, strategic competition is not a new phenomenon. Matthew Kronig in his book The Return of Great Power Rivalry expertly outlines this concept and highlights the sheer advantage of democracies time and time again. In nearly every single period of history where global powers have clashed, democracies and their alliances have deterred autocratic threats. However, as the United States advances further into strategic competition, there is a perception that autocracies such as China and Russia have the advantage. The theory of centralized power and the capacity to wield resources to maximum effect with a short chain of decision makers makes Russia and China more agile through acquisition of technology, adaptation of tactics, and overall influence across all levels of war. The United States can make up for this perceived adversarial advantage through an opposite approach – radically decentralized decision making across all levels of the bureaucracy, through an empowered force of inherently innovative American people. The American people who fill the ranks of all services are culturally capable to incur risk, challenge the status quo, and ultimately find any way to win.

The Western edge fueled by democracies, now further accelerated by the American advantage, has shortened kill chains for centuries. From the introduction of the musket to cyber warfare, the progression of technology has helped shape the way the Western world has evolved. In War Made New, Max Boot chronicles the development and impact of Revolutions in Military Affairs (RMA) and accentuates leaps in strategic perspectives through tactical adaptations on the battlefield. Warfighters for generations have found new ways to kill faster, project power further, and sustain combat longer to overwhelm opponents. These military adaptations, in parallel to the movement of global hegemons, persist to shift westward. Rarely has the world seen an Easternization of tactics or technology implemented in combat. Victor Davis Hansen in Carnage and Culture explores this concept voraciously. Not only have resources and capabilities continued to favor the West, it is the culture of inclusion within Western civilizations which ultimately drives innovation across all aspects of society. This can be seen through post-Enlightenment thinking through the convergence of ideas. The classic theoretical perspective of popular sovereignty also contributes to the desire that the power comes from the people. Simply put, there is an inherent advantage and precedent for the United States to win not only because of technology but because of people. The collective spirit and inclusion of warriors to find efficiencies in combat, regardless of any superficial qualification, are proven elements that give armies the edge.

Despite these advantages, the American military has continued to erode its competitive advantage. The decline of American military supremacy can be bookmarked by historians during the Vietnam War, some would even argue this decline initiated at the onset of the Cold War. At all levels of war, the American military devolved into an organization permeated by toxic leadership and an expanded bureaucracy influenced by the military industrial complex and the court of public opinion. The distaste for the quality of leadership through the Vietnam era can be quantified through the number of officers and non-commissioned officers killed by their own men, to the entire Joint Chiefs of Staff which nearly resigned due to the climate and decisions made by the President of the United States. While this may not be indicative of a lack of inclusion, it certainly has detracted from it.

Now while the product of the Vietnam War has supplied our society with a volunteer force who want to serve our nation, it has also produced a stagnated model of leadership which values the status quo and does not serve its people. In a robust study of general officers from World War II to modern-day, Thomas Ricks in The Generals cites professional military education and the values of the American military system which have driven generals from experts in combat to politicians. This devolution has not stopped as layers of bureaucracy continue to pile on top of the system, and the frozen middle halts the progression of critical military adaptation. The emergence of the complexity of weapons of war juxtaposed by the regression of basic human elements of culture represents a critical vulnerability only reinforced by a change in direction. The American military cannot afford to take any more steps backward, especially as the world continues deeper into the Information Age.

Ideas are also drowned in antiquated connotations of military thought which date back further than Vietnam. The methodologies American military leaders have subscribed to have inadvertently atrophied strategic thinking despite the prestige of their origins. This is not to ignore the Western philosophies which have provided the United States a construct which has proven capable in the field of battle. Instead, we must question the emphasis of military thought of the 19th and early 20th Centuries, or at least what Americans have chosen to dissect. Dr Jőrg Muth highlights this misapplication of military thought in a microcosm:

“Interestingly, the literally hundreds of American observers who were regularly sent to the old continent during the course of the 19th century to study the constantly warring European armies completely missed out on the decade long discussion about the revolutionary command philosophy of Auftragstaktik. Instead they focused on saddle straps, belt buckles and drill manuals. This is one reason why the most democratic command concept never found a home in the greatest democracy. The U.S. officers simply missed the origins because of their own narrow-minded military education.”

Overemphasis on granularities of military science have the potential to spiral nations and empires into defeat. Leaders have dismissed catastrophic losses as a result of strategic oversight and instead become mesmerized by tactical excellence – just look at the American obsession with the German way of war. This love affair with highly technical preparation for battle has only been perpetuated in the 21st Century by general officers eager to dictate fire team level decisions from thousands of miles away. The absence of the voice of warfighters, who have been ignored in the labyrinth of bureaucracy at home station, even find themselves constrained in combat. A mission capable rate cannot measure the negative implications of readiness from this apparent lack of trust through overly centralized command. It is more important than ever that American military leaders calibrate their perspective to meet the demands of competition which exceeds the boundaries of the battlefield itself.

The power of the individual warfighter has not been overlooked by all military leaders over the course of this decline. There have been advancements in military strategy from John Boyd, the foundation of maneuver warfare by the United States Marine Corps, the United States Army’s push for Mission Command, and even as recent as the rhetoric from the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, General CQ Brown, Jr., with his Accelerate Change or Lose action orders published in 2020. Boyd was not an old decrepit academic when he conceptualized and codified the Aerial Attack Study and Energy Maneuverability Theory, he was a young officer – it remains Air Force doctrine to this day. Even in General Brown’s Accelerate Change or Lose action orders, individual action is emphasized over bureaucratic processes. Maneuver Warfare doctrine calls for the “Strategic Corporal” to make decisions that could possibly affect an entire campaign. All of these examples encapsulate or represent a methodology that trusts people at the lowest levels to take risks and lean forward into decision-making.

However, these advancements in concepts are the exception and not the rule. There is still a pervasive notion that our leaders do not care to listen at the lowest levels, and that can be reflected in steepened retention rates for first term enlistments. In response, the Marine Corps’ Talent Management 2030 is a step in the right direction for American military institutions to holistically approach or at least perceivably genuinely attempt to fill the gaps of human potential within services. From an operational perspective, Tesseract – the Air Force’s Logistics Office of Innovation – has established itself as a mechanism to untap the potential of frontline Airmen and contribute to strategic initiatives. A growing number of initiatives which empower change agents exist, but represent only a small subset compared to the rest of the Department of Defense. Without leaders across the Joint force built to mobilize these methodologies, the United States military will not see the American advantage leveraged to its full potential and will detract from optimal strategic effect. As an entire Department, the American military must establish a system to unleash the potential of the talent which exists. The core of this potential is unlocked by leaders who pair perspectives down to the lowest levels. The sergeant covered in grease; the lance corporal caked in mud; the captain burdened by decisions.

Warfighters can lead the way through this culture change – they cannot wait for the institution to conform. As Americans prepare for what may come, warfighters must shed the burden of bureaucracy and challenge the status quo. And yes, this is a two-way road – leaders at all levels must create a space where people can share. Voices must be heard even by those who are not in a hierarchical position to traditionally influence change. The power and potential of the American advantage should not be stifled by strangers to strategy sitting in a windowless room. Regardless of rank, warfighters should take every chance to share perspectives and open a dialogue which advances military thought. No one will play to the tactical edge if warfighters choose to not tell their story. An idea can change the world – it’s not too late to make an impact.

Millennials: Society’s Misfits… GWOT’s Heroes - Hector Fajardo

We’ve all heard the allegations about the Millennial generation; that they are just a byproduct of a spoiled, immature, and selfish society, who are at times unreliable and weak. Millennials are also described by some as lazy, narcissistic, prone to jump from job to job, and needy for appreciation and rewards.

Is this true? And if so, are Millennials redeemable? Well, the first thing we should do to answer those questions is to define our terms. Millennial is a label branded upon individuals who were born between 1981 and about 1996. Originally named “Generation Y” as they follow the “Gen X” group, they were later given the moniker of Millennial.

I was born in 1978, which makes me part of the “Gen X” group. I grew up in a world without the internet, cell phones, affordable cable tv, or easily accessible video games. My upbringing was in stark contrast to that of current generations, including the Millennials, which makes my experience with them somewhat incompatible. I served in the US Marines in the early 2000s, making most of my leaders what some would consider “old school” Marines. Being lazy, selfish, conceited, and in need of acceptance was not only seen as ridiculous, but worthy of reproach. Anyone who did things back then for the mere expectation of rewards would not make it too far without a serious butt chewing. Now, this is not to say that the way in which the military, especially the Marines, handled their people back then was any better or worse than the way they currently deal with Millennials. It was just different, and based on my observations, it served its purpose.

So now that we understand the stereotypes and societal customs attached to Millennials, one question remains: Do those traits and characters also describe the Millennials who served during the Global War on Terror? It is not news to anyone that a certain number of military Millennial folks do carry a few of the stereotypes granted to them, but the truth is that some of the greatest examples of heroism and gallantry committed during the GWOT, took place at the hands of that group. When America placed the call of war, the ones who answered it, and continued to answer it for 20 years, were none other than the Millennials. Among those ranks are mighty warriors like Jason Dunham, USMC; Kyle Carpenter, USMC; Salvatore Giunta, US Army; Dakota Meyer, USMC; Matthew O. Williams, US Army; Florent Groberg, US Army; Zarian Wood, Navy Corpsman; Matthew T. Abbate, USMC; Nichole L. Gee, USMC; and many more like them.

What made the group listed above break the stereotypes that so many of their peers carry on their shoulders? This is a question that has many layers and answers, but in my opinion, it comes down to one thing: upbringing. The environment where a young person is raised and groomed, as well as the home where they learned and experienced their youth is fundamental to how they will face life as adults. Parenting, as an important variable, can be critical to a person from childhood. Children raised in homes where a strong parenting influence exists have a greater chance of facing obstacles and moral challenges. Having supportive and involved parents, as experts claim, shows children performing better than their peers who do not (Williams, 2016).

In his book, “You Are Worth It” Marine combat veteran and Medal of Honor recipient, Kyle Carpenter, explains how his upbringing in rural Mississippi was fundamental to the person he became. Kyle narrates fascinating stories of the times that he, his brothers, and his parents spent together. He described himself as a “fearless, restless, reckless, relentless… ball of energy” (p. 21), crediting his parents for teaching him to be honest, to believe in himself, and to assure him that the time they spent with him, and his brothers were meaningful and deeply personal. When he deployed to Afghanistan in November of 2010 and was forced to confront unimaginable odds, he reverted to what he knew and who taught it to him. His accounts after he absorbed a grenade blast with his body, and his difficult post-recovery are nothing more than miraculous, yet one thing always remained in him: His understanding of the love, support, and courage displayed by his family.

While Kyle’s case is amazing and inspiring, it is obviously personal. And while the definition of family and home support systems may be different from one person to the other, a common pattern in Millennials can be deduced. When they have a strong and positive upbringing, where they are allowed to challenge their fears and doubts and are provided as many tools as possible to accomplish their goals, they stand out from their peers. This truth can be said about Millennials in occupations, other than the military.

After I left the Marines, I became a police officer. I have been one for close to two decades. One of my tours of duty was as a Field Training Officer. My job was to teach street-level investigations to brand new cops from the academy. I had the opportunity to instruct people of my age, some a little older, but mostly of the Millennial generation. With the “Gen X” cops I learned that all I had to do was order them to do something and they just did it. They weren’t perfect, but they seemed to adjust to the structure of policing with ease. With Millennial cops, however, I quickly found out that a better way to teach them was by knowing their backgrounds and their understanding of life and authority. I was able to contrast those who came from homes that instilled hard work, a spirit of camaraderie, and a willingness to learn, with those from homes that catered to every wish they fancied. The latter required a lot of my patience and energy, but with hard work, we were able to accomplish what we set up to do. Many of my Millennial police trainees who also had prior military service behaved and carried out their jobs much differently than those who did not. They were used to orders and rank structures, and for the most part, had a better grip on multi-tasking and stress management. Millennial cops who did not have military experience, while not being less effective or engaging than their veteran peers, did require more of my time exposing them to stressful situations. I took the time to teach them how to use their skills, personalities, and strengths to overcome their fears and their lack of “life experience.”

I understand that many variables make up an individual’s personality. Some people may come from wonderful and loving families yet choose to become the opposite as adults. Others could have difficult upbringings yet make sacrifices to make a better life for themselves. What I experienced as a Marine and as a cop when dealing with Millennials is that they understand the world around them very differently from the way I do. They are highly influenced by the digital world and the massive amounts of information that come from it. And just like those of us who grew up before them, the types of information that they were exposed to as children had a tremendous influence on whom they became as adults.

One thing is certain, Millennial Americans fought their hearts out the last twenty years of war in places and situations that many others would not have even imagined. They used their talents, their technology skills, and their savviness in communications and people, to carry out complex and difficult missions. They were essential in ground operations against formidable foes and were fundamental in creating relationships with local populations. They saved lives and gave people hope, all while bringing lethality to the enemy’s door. They were the right group of people for the right type of war if there is such a thing. Millennial warriors left a legacy in our Armed Forces, and for that, we ought to be tremendously proud of, and grateful to, them. 3

GOONS: What Hockey Enforcers Can Tell Us About The Infantry - Mac Caltrider

I debated the title of this essay for about as long as I spent writing it. “Goon” is played out in GWOT circles. Usually plastered on t-shirts with skulls donning quad-tube night vision, being worn by guys who never laid a finger on such expensive equipment. Originally meant to convey a penchant for violence, “goon” now screams of someone struggling to find their identity after their military service has ended. But the term “goon” has long been associated with Hockey enforcers, and it's through that unique role on the ice that we can come to better understand the kind of men who choose to walk the long and lonely road of the grunt.

Six years ago I was flipping through Netflix trying to find something to put on for background noise. I ended up landing on a sports documentary titled Ice Guardians about the role fighting plays in Canada’s national winter sport. The movie wasted no time grabbing me by the throat. Whatever I had been paying attention to was quickly replaced by the violence on my TV. I’ve never played a day of hockey in my life. I don’t even know the rules well enough to play an NHL video game without having to turn off penalties, but watching those enforcers go to work on the rink captivated me. When the final credits began to roll, my cheeks were wet. I was crying like a friend had died.

What was it about these athletes brawling on the ice that put a lump in my throat? Watching burly New Englanders and Canadians swing away at each other, with teeth flying and knuckles breaking, was reminiscent of something I couldn’t put my finger on. Something about the way they dutifully took to the ice, knowing full well they were about to suffer tremendously on behalf of their teammates, while the hot-shot goal scorers soaked up the glory spoke to me. It wasn’t until I rewatched the movie recently that I understood why.

The enforcer’s role in ice hockey (to protect his teammates through violence) is the closest example we have in sports to the role of the infantry within the armed services. They share a similar moral code and exist in bubbles of tribal violence the rest of the world views from an outsider's perspective.

Like enforcers, the infantry is full of volunteers who also chose a taxing and thankless path in their respective arena. Among the few Military Occupational Specialties that exist with a primary mission of killing the enemy, the infantry is unique for its very status of not being special. Unlike comparably deadly jobs within special operations, no one joins the infantry to be showered in accolades, uniform trinkets, and fancy colored hats. Rather, grunts join simply to serve in the military’s oldest and dirtiest job.

People sometimes view the infantry as composed of men who chose to be ground pounders due to a lack of opportunities. Outsiders (both civilian and military) often regard grunts with revulsion for their willingness to wade into the mud and guts to kill other humans with smiles on their faces. Society knows the infantry is necessary, but they’re uncomfortable looking at it. Americans don’t know what to make of a group of teenagers who endure bad weather, outdated equipment, and poor rations for a chance to bury their bayonets into the bellies of living targets. Their zeal for violence masks the noble virtues that drive them to choose such an outwardly ugly path.

In Ice Guardians, American author Howard Bloom sheds light on a similar path while describing the complicated nature of hockey enforcers.

“Is there a virtue that's overlooked by those who look at hockey? You bet. But you don’t know it until you step into the locker room and interview one of these guys. You think, “this guy is a monster”. You think he has no compunctions about breaking arms, breaking legs, smashing out teeth. You think he’s merciless — that he should be exterminated, that he’s a cockroach to the game. Then you sit down with him and discover he has the most magnificent set of ethics and morals that you have ever seen in your life [...] What does the enforcer call on? Profound loyalty. Loyalty so deep that he’s willing to risk his own structure — his own body, his own bones, his own teeth, his own brain on behalf of protecting people he deeply loves. The enforcer is the most ethical and moral member of the tribe because he is willing to undergo such incredible sacrifice. That’s looking at it from the inside of the group. Looking at it from the outside of the group, the enforcer is the ultimate enemy, the super bad guy, and must be eliminated [...] if we were looking at the enforcer from within the group that the enforcer defends, we would love the enforcer because the enforcer loves every one of us so much he is willing to give his life for us.”

Bloom’s illuminating take on enforcers also applies to the grunts. From outside the infantry tribe the grunt is ugly, merciless, and a politically incorrect cockroach. But from a perspective within the tribe, he’s loyalty incarnate. He’s willing to sacrifice his body, brain, and even his life out of a tremendous love for the group.

The most obvious cinematic example of the enforcer archetype as a member of an infantry unit comes in the form of Full Metal Jacket’s M-60 weidling Animal Mother. The sleeveless machine gunner is not the designated leader of the group, but he’s the undisputed alpha male, and when the squad leader balks in the maelstrom of combat, “Mother” steps up and assumes the role of enforcer. He dishes out violence at the rate of 600 rounds a minute and exposes himself to extreme danger in order to protect his teammates. His protective nature is why he assumed the dual-role of being the unit’s most violent member as well as the one who places the welfare of the group above his own. When two Marines in the squad are shot by a sniper and left writhing in the open, Mother is the only one who never considers remaining safely behind cover. For him, the only option is to place himself in danger for the sake of the squad. For Animal Mother, being the enforcer means placing the survival of the entire unit before his own safety, regardless of whether or not he likes them on a personal level.

Sebastian Junger came to the same realization when he embedded with a platoon from the Army’s 503rd Infantry Regiment in Afghanistan. In his 2010 book War, Junger writes, “Brotherhood has nothing to do with feelings; it has to do with how you define your relationship to others. It has to do with the rather profound decision to put the welfare of the group above your personal welfare. In such a system, feelings are meaningless. In such a system, who you are entirely depends on your willingness to surrender who you are.”

Junger and Bloom are both describing the same segment of human nature that drives young men into such uniquely violent roles. Ironically, enforcers and grunts often have more in common with their opponents and enemies than their teammates and comrades. Respect between enemies stretches back beyond Bantius and Hannibal and continues today. It’s not uncommon for a veteran of Afghanistan to marvel at the bravery of the men who willingly faced down America’s military might with little more than sandals and AK-47s. Similarly, enforcers share a mutual respect that runs deeper than the name on the chest of their jerseys.

“Oddly enough, the guy you’re squaring off against probably understands a lot more about your role and your day to day mentality, than all those teammates and those people you live with because he’s doing the same thing,” says Kevin Westgarth, who played 169 games in the NHL as an enforcer.

Though neither enforcers nor infantrymen let respect for their opponents get in the way of doing their duty, it’s a strange aspect of the job that outsiders have difficulty understanding. As the Western world continues its misguided march toward political correctness, neither professional sports nor the military are spared from the demand to substitute bloodletting for gentleness.

Just as calls to make the military more welcoming and fair are prioritized over maximizing lethality, hockey has come under fire to rid itself of what some consider meaningless violence. While the military’s efforts to expand opportunities for all are noble and founded in equity, they are often misguided. Likewise, calls to remove fighting from hockey are born of a forlorn hope to create a more palatable spectacle.

“These players are the ones involved in the game. They’re the ones consenting to that level of violence. They’re the ones making their living in that context. At what point do we say, ‘We know you all agree with that, but we decided we know better than you and we’re gonna take it out of the game.’ And at one point do we actually say, ‘No, you’re the ones involved. You know what you’re doing,’” says Dr. Victoria Silverwood of NHL players advocating for enforcers to remain a part of hockey.

Her advice should be applied to the military as well, especially the infantry. Perhaps when active duty Soldiers and Marines raise concerns about the military’s shift in focus away from lethality and preparedness to fairness and inclusivity, those of us on the outside should listen. Who are we to say we know better than the men in the arena?

So what makes the esprit de corps so strong among infantry battalions? It’s the philia born of shared adversity in selfless service to others. While an ice hockey team has one enforcer to protect the group, a squad of grunts all share the role of enforcer. Every member of the group is charged with protecting the others.

During his time in Afghanistan, Junger asked one American soldier if he would willingly risk his life for other members of the platoon. Unsurprisingly, his answer was a resounding, “Yes”. That level of shared commitment to the group has a profound effect on those who’ve lived it. It’s why leaving the military can be more traumatic to a person than the worst things combat has to offer. It’s why severely wounded men eagerly return to their units. It’s also why, when asked if given the chance to start his hockey career over would he choose the same path, 12-year NHL enforcer Kelly Chase began to cry. When he finally composed himself enough to speak, the former goon nodded and simply said, “With a little more fire.”

Opinion

Op Eds and general thought pieces meant to spark conversation and introspection.

Losing Our History in the Age of Information - The War Murals Project

We live in an extraordinary time of connection and connectivity- I recall being struck by that notion in 2018 when even at a remote Iraqi FOB surrounded by bombed out buildings that I was still able to connect to the Wi-Fi network at the chapel tent named ‘A Signal from God’. It has truly never been easier or faster for a deployed military service member to connect with their friends and family back home and create and share photos, videos, messages, and other records.

With this massive benefit comes an overlooked risk beyond the growing threats posed to operational security by having an online presence- what is created digitally can just as easily disappear- the records and data we are drowning in incentivize being shared for an instant, not saved. This information quickly becomes overwhelming to organize and analyze. The things you experienced 2 phones or 1 laptop ago can quickly be lost forever and even that hard drives many use to store their old deployment records can only be relied on for maybe 8 years in reasonable conditions either due to a component failing or the data simply decaying on the device.

This creates a knowledge gap for both veterans and the military that went on for years after the Global War on Terror (GWOT) began and that only gained the attention it deserved when several journalists began publishing articles on how the US Army was systemically failing to keep field records, after action reports, and contextual lessons of units and areas of responsibility. What was once reported and filed away by higher commands remained on computers in austere environments. If they didn’t break in the harsh environment they were in, the computers were all to often reimaged and mountains of poorly managed electronic records were deleted when new units took over, bases were closed, and new priorities were made. It was not until 2013 the Department of Defense began a focused effort to recover and consolidate field records from the wars, yet despite these initiatives (Publica, 2013), the gap continues to this day as highlighted by the U.S. Military Academy’s Modern War Institute in 2017:

"Even for those wars with no living veterans — whether the American Revolution or World War I — we can remember. We can access digital archives of battlefield maps. We can examine lists online of personnel who fought in each battle. We can read written orders from commanders, or personal diaries, journals and letters sent by soldiers to their loved ones. Unfortunately, our recent conflicts will be difficult to remember this way. That is because for the first 10-plus years of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the military lost or deleted a majority of its field records. And, although the military has since made a greater commitment to preserve records, an outdated archival system limits their usefulness." (Spencer, 2017)

If these institutions of the US military can recognize the risks here and still come up short, we should reflect on what veterans of the GWOT can do individually as we move further from the conflicts and try to remember and explain the history of 'the forever wars' to our comrades, families, and community.

In my work connecting with veterans and doing online research for the War Murals Project (The War Murals Project, 2022) I have heard the frustration from vets excited to find the site and plug in their dusty computers and old flash drives to share their photos of the deployment art and war graffiti the project focuses on, only to find components broken and the data corrupted. Access to old emails is lost, or the site that was hosting their old war blogs and digital diaries shut down. Even later deployments in the 2010s that were better documented on social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram have some significant limitations- have you ever tried to find old photos on that platform? What about rereading old messages? Maybe one was diligent enough to pool things together into an album but almost all that information is otherwise disorganized, unsearchable and without context on a platform that isn't guaranteed to be around for as long as you will.

Hopefully historical archiving systems on platforms and devices will mature, but in the meantime individuals ought to be smarter than their grandfathers about how their experiences are preserved since most no longer just shove their papers, photographs, and letters home in an old footlocker in the basement for decades where they are often just as legible as they were the day they were put there. That means backing your device’s files up onto a hard drive, backing up that hard drive into the cloud, scanning old photos you only have printed, printing out photos, saving copies of an old blogs and articles elsewhere, and forwarding your old emails to another account; because history, and the lessons we can get from it, gets lost forever, surprisingly quickly.4

“I Read Your Book!”: An Argument for Broader Reading - Aaron Lawless

Almeria, Spain, 1969. A stern-faced man in a helmet with three stars gazes through binoculars at men in American and German uniforms dashing across a battlefield. Suddenly, his expression breaks into a grin as the battle unfolds, and the American troops force a German retreat. “Rommel, you magnificent bastard,” he exclaims, “I read your book!”. The film cuts back to scenes of exploding tanks, infantry maneuvers, and air combat, replicating the 1943 battle of El Guettar in North Africa. The man is, of course, George C. Scott portraying George S. Patton, Jr., on the set of the 1970 film Patton.

FM 6-22 states in chapter four that, “Books and other written material may be key learning resources for self-development.” As a component of self-development, a structured reading program supports a broad spectrum of learning – but what to read? Although a dramatized account of the North African campaign, Patton offers at least one lesson to the modern Military Intelligence professional; to know the adversary, read what they say about themselves. Army leaders, particularly in MI, must study the doctrine, cultural material, and military philosophies of adversary and competitor nations in a deliberate and conscious effort to expand understanding of the operational environment beyond Western military theory and history.

Army officers and leaders frequently rely on General Officer reading lists as the standard for their self-developmental reading. This is, after all, the reason senior leaders publish reading lists. However, a cursory examination of available reading lists, from the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to commanders of Centers of Excellence, reveal some shortfalls. Out of twelve senior leader reading lists examined for this article, six included books from non-Western authors, including two lists which feature Sun Tzu. The remaining four reading lists present a varied selection of academic authors, notable government officials, and at least one former Soviet soldier. In total, only twelve authors out of over one hundred books on senior reading lists provide direct insight to non-Western thinking.

One caveat however , this article is not to denigrate senior leader reading lists. Leadership, organizational studies, military history, and readings that foster diversity in our ranks all have their place and deserve thorough study. Senior leader reading lists in their present state remain more than valid as a framework for self-developmental reading. Nor is fiction valueless – Admiral (RET) James Stavridis recommended fiction as a method to broaden creative thinking in a 2010 article published by the Australian Defense Force Journal. However, for the professional who desires insight to adversary doctrine, thinking, and worldview, these reading lists cannot be the sum total of professional reading.

Critical thinking requires examination of perspectives radically different from that of the Western way of war. We cannot read only material that we already agree with, that already makes sense to us, and call it development. Leaders must consume something that does not make sense to them, understand that it does make sense to somebody, and then incorporate unfamiliar ideas accordingly. As the military moves towards increased diversity, as it should and must, intellectual diversity remains as important as ever. Jomini and Clausewitz are influential in the West, yes, but are their models truly universal? Would a company commander of the People’s Liberation Army or a brigade commander of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps read Clausewitz and concur? These questions, and more, demand serious attention to the study of adversary doctrine, military history, and philosophy – with particular emphasis on studying the adversary’s own words on these subjects. Get inside their head, walk a mile in their shoes, and be better prepared to defeat them in close combat.

Of course, barriers exist. As John Pomfret wrote in 2019, “The Chinese language is the first level of encryption.” Translation into English is the first step, as with the work of the Foreign Military Studies Office. The Russian Way of War, by Dr. Lester W. Grau and Charles K. Bartles, demonstrates one example of the kind of self-developmental reading that military professionals need. Translations and syntheses of foreign-language books allow readers to expand their perspective and incorporate an adversary’s worldview to their battlefield calculus. Self-development is still an individual responsibility, so it is incumbent on individuals to consume the adversary’s published thoughts wherever they can be found in a language the reader understands.

Although some key texts may be out of print or not translated, reading adversary history and doctrine from their viewpoint remains a key facet of intelligence professional development. Self-development must expand beyond lip service to senior leader reading lists to incorporate perspectives other than Western or Eurocentric ideas. Combat arms and intelligence leaders at all levels must expand their intellectual horizons to understand how adversaries view themselves and what informs their worldview. To do less is a disservice to our fundamental purpose.

Historia Belli Mei : A Story of My War - Tamim Fares

I was a weird kid. Often in trouble, difficult to deal with and generally anti-social in nature. From my earliest memories I was obsessed with war and combat. My heroes were men like Lee Marvin, Steve McQueen, Richard Burton and Clint Eastwood. My favorite movies were the silver-screen exploits of World War Two legends that aired continuously on TCM and AMC. There was no tradition of martial service in my family, no one present who could dissuade me from my fanatical preoccupation with war. My grandfather had peacetime duty in Europe and my father deserted the Iraqi Army during their devastating conflict with Iran. My only exposure to the mythos of war was through books and the films they spawned. Despite this–or perhaps because of it, I had an insatiable appetite for stories of heroics and glory. But more than that, I craved the experience of combat itself.

I took the leap at nineteen, lying to my family and flying half way around the globe to fight in a war my father despised and which I felt moral ambiguity towards. I wanted combat, so there was no question I would be enlisting for the Infantry. It was a decision that took my family–when I finally called them after arriving at basic training–completely by surprise. The war was raging in Iraq and the Army needed bodies. I couldn’t pass a PT test and was dangerously underweight with terrible vision, but they took me anyway. More meat for the grinder.